A Model for Purposeful Action

In this chapter, you will explore four key concepts that help individuals and organizations navigate their work more effectively:

One way to understand work in organizations is as people making interventions to fulfill a purpose.

Purpose informs, motivates, and guides action. Interventions are specific steps people take, and/or the constraints they put in place, to fulfill a purpose.

Although people making interventions to fulfill a purpose sounds intuitive and straightforward, in practice, there are many fail points that can lead to undesirable consequences or waste. Common examples include the following:

- Lack of clarity around objectives: People act without understanding the purpose behind what they are doing.

- Misalignment: The purpose of a specific decision or action does not align with the organization’s broader goals or priorities.

- Disagreement on viability: There is disagreement about whether a purpose is valuable or worth pursuing.

- Divergent opinions: People have differing views about the purpose behind a decision or activity.

- Diverse implementation perspectives: People have different perspectives on how to fulfill a purpose.

- Ineffective interventions: The activities intended to fulfill a purpose turn out to be unsuitable or insufficient, from the beginning, or because circumstances changed in the meantime.

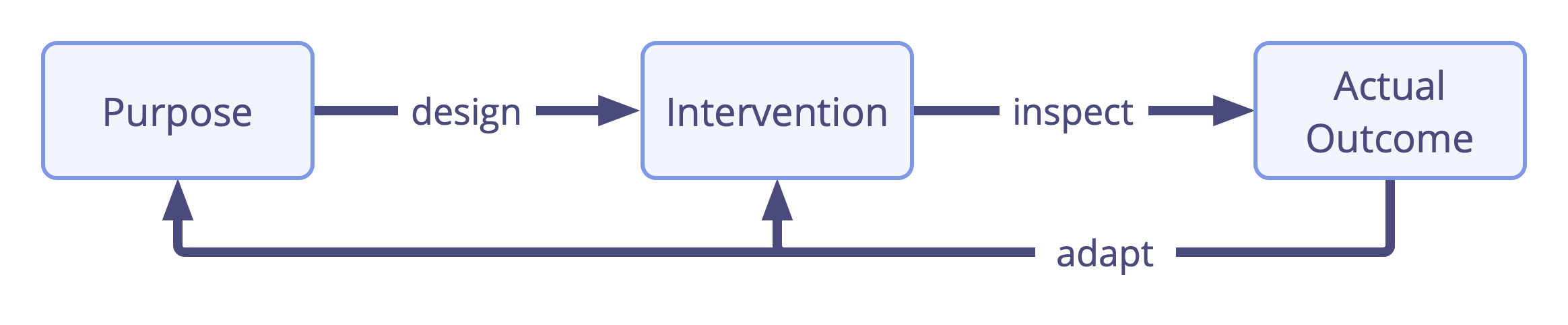

- Lack of effective feedback loops: There is no review of whether interventions are achieving their purpose, or no follow-up to improve or adapt them.

It’s much easier to avoid or at least detect and mitigate those fail points when all stakeholders share a common understanding about how to describe and discuss purpose and interventions clearly and coherently.

Understanding and describing interventions is often straightforward; you list the specific step(s) you take and/or the constraint(s) you put in place to fulfill a purpose. Clearly understanding and describing purpose, however, can be more challenging, and there are several ways to do it.

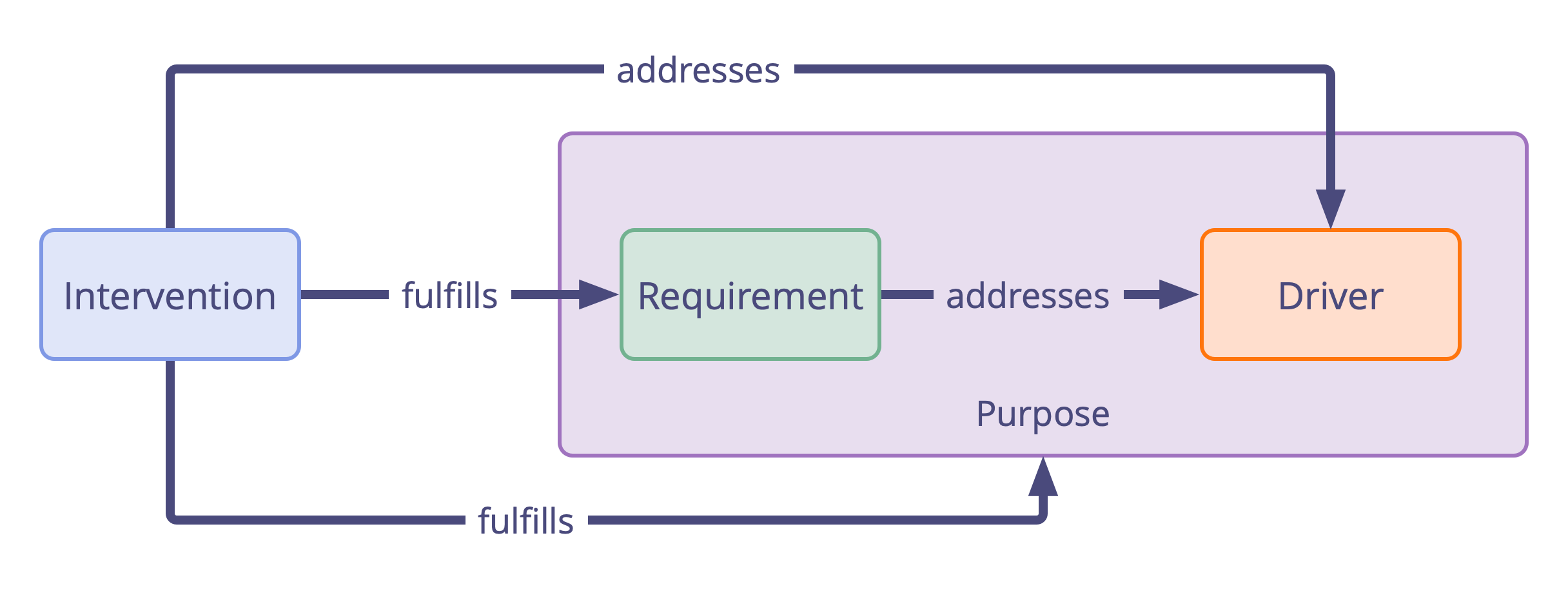

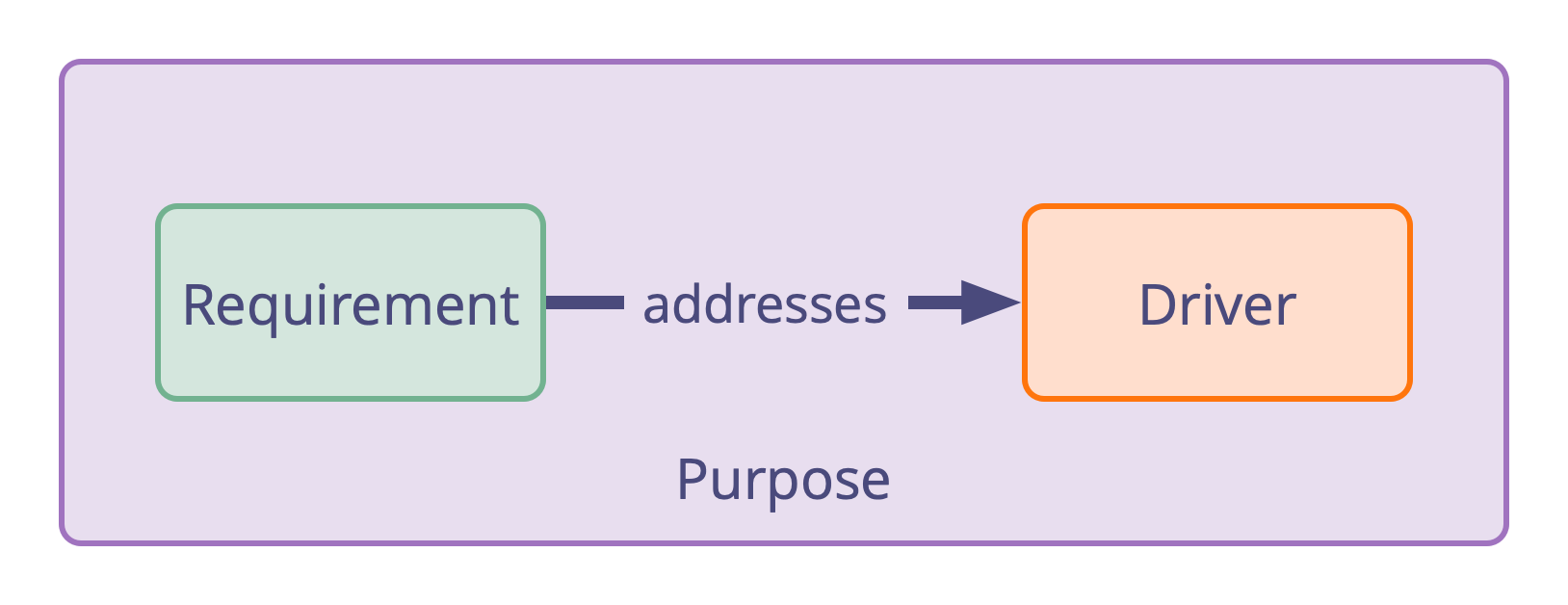

One way to understand purpose is as the confluence of a situation that is relevant to address, and the outcomes considered valuable to achieve in relation to that situation. To define purpose, we use two concepts:

- Organizational Driver: a situation of relevance that you want to address.

- Requirement: a state considered valuable to establish or maintain in order to address a specific driver.

Clarifying both the organizational driver and the associated requirement makes it much easier to determine a suitable intervention.

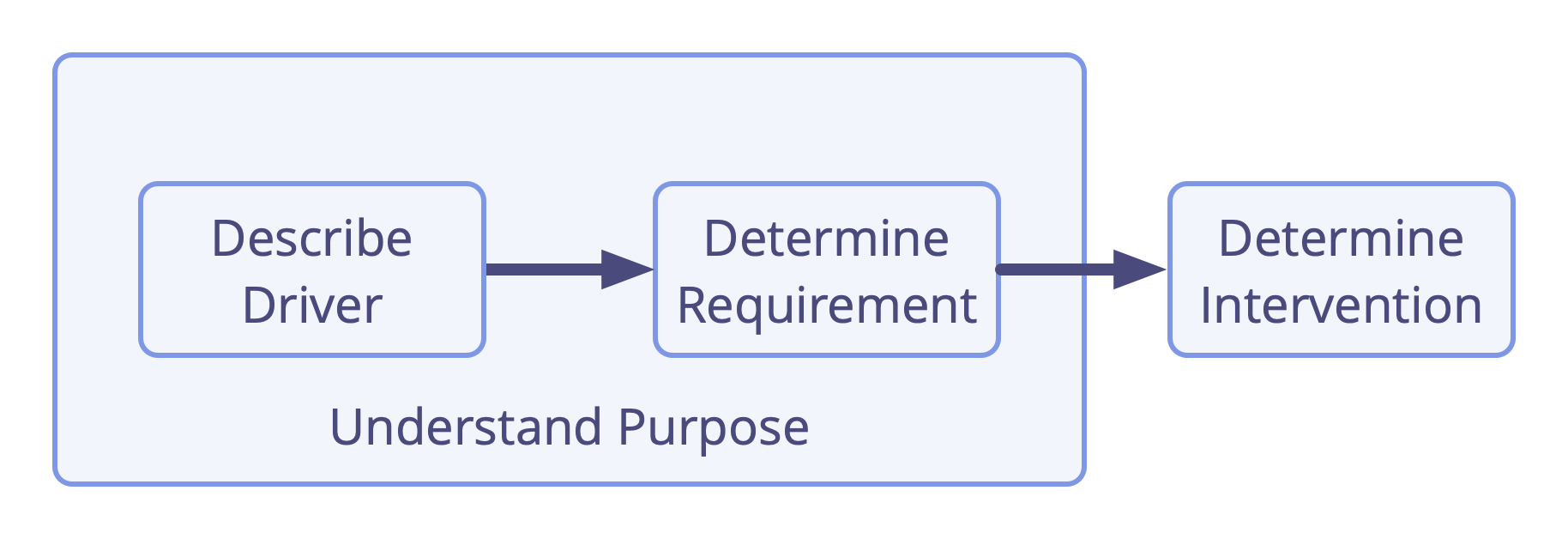

There is also a natural sequence to this approach: A clear understanding of the situation of relevance is essential to determine a suitable requirement. Understanding the requirement itself (or at least, a grasp of a valuable outcome) is necessary to determine an appropriate intervention.

Breaking down the process of responding to relevant situations into distinct, sequential steps helps prevent misdiagnosis, reduce wasted effort, and avoid implementing solutions that fail to address the situation in a suitable way.

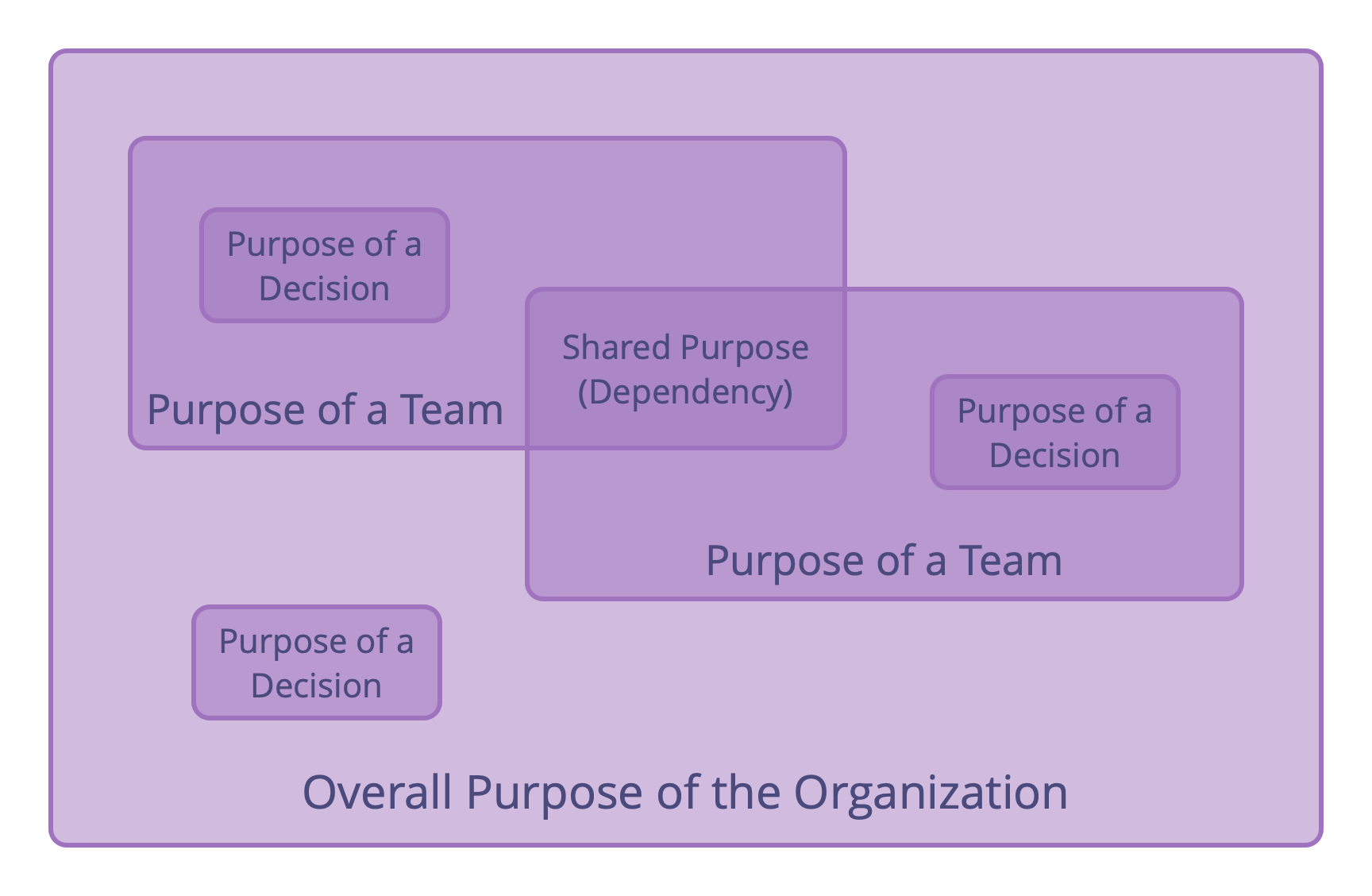

This model also helps to visualize interconnected purposes, supports shared understanding, better communication, and more effective evaluation of whether specific interventions are achieving the outcomes intended.

Ensuring coherence is often complex: each intervention needs to be suitable for fulfilling the purpose it is intended to serve, but it must not impede the fulfillment of other organizational purposes. It also needs to be aligned with and valuable in light of the organization’s overarching goals. This complexity arises from the interconnected and interdependent nature of things and from the difficulty of clearly delineating where one aspect ends and another begins.

In essence, for people in organizations, this framework serves as a practical roadmap that turns vague intentions into concrete, purposeful actions. It supports better resource utilization, stronger alignment, a more focused approach toward achieving meaningful outcomes, and greater capacity for learning and adaptation over time, as supported by the patterns in S3.

How the Model Helps

The model for purposeful action provides a lightweight and conceptual framework that reveals a simple underlying architecture behind all decision-making and activity in organizations.

The model can shift how people perceive organizational dynamics through the conversations it triggers. By understanding purpose, relevance, and relationship to the whole, people begin to “see the system” — recognizing interconnections between decisions and their relation to overarching purpose. This reframing is often transformational.

On the most fundamental level, the model helps people understand why they should act and to what end before they decide what to do and how. It enables insight into relationships between decisions by connecting and aligning what you decide and do with what other people are doing in the organization. It helps surface misalignments (e.g., interventions happening in parallel that should be connected but aren’t), supporting learning and adaptation across systems.

It can be used to map out, understand, and evolve the structure of interrelated purposes and interventions throughout the entire organization, from the purpose of the organization itself, all the way down to any simple operational intervention.

While applicable across many contexts, the model is specifically designed to support organizational life: it brings attention to purposeful activity, facilitates coherence across interdependent efforts, and encourages learning and adaptation over time.

The model is universally applicable, regardless of your organization’s structure and how you choose to categorize and manage work and decision-making.

Once you understand the concepts and relationships this model is built on, you can start using it right away — both for your own thought process and in your conversations with others — to improve your capacity for sense-making, meaning-making, and decision-making, and increase your chances of recognizing what’s working and what may be valuable to change or improve.

The model also works seamlessly with any tools you are currently using for visualizing decisions and work, from pen and paper and wall boards to Miro, Jira, or Google Suite.

Purpose

Everything you do serves a purpose, even if you might not always consciously choose that purpose or be aware of it. Deliberately considering the purpose before taking action helps ensure that your actions contribute to achieving that purpose. What seems purposeful in isolation might not make sense when you step back and look at the bigger picture. To make the best use of resources, energy, and time, the purpose of your actions must align with your broader goals. This applies to organizations as well.

Purpose is the reason why something is done, used, or created; a guiding motivation that directs actions, decisions, and resources toward achieving a valuable outcome.

Considering purpose helps people make sense of what’s important to focus on and fosters a shared understanding of what may or may not be beneficial to do.

Reflecting on purpose supports:

- Sense-making: understanding situations that motivate action

- Meaning-making: establishing whether and why a situation is relevant to respond to

- Decision-Making: determining direction and scope for a suitable response to the situation

Purpose at the Center of the Organization

Every organization has an overall purpose it serves, whether it’s explicitly defined and widely understood or not, and the effectiveness of an organization depends on its members’ ability to contribute toward fulfilling that purpose.

Therefore, ensuring the overall purpose is clear and explicit helps members align their priorities and actions to that purpose while avoiding wasting effort on activities that do not contribute meaningfully.

As an organization evolves and the context in which it operates changes over time, its overall purpose might need to be refined to ensure the organization remains relevant and effective. This is why it’s essential to periodically evaluate whether the organization’s purpose is still worthwhile pursuing and to determine whether adjustments are valuable or required.

Just as a project or team within an organization can outlive its relevance, the organization itself may reach a point where its purpose is no longer meaningful in its broader context. At that point, the organization must either redefine its purpose or cease to exist.

Organizations are Complex Networks of Interrelated Purposes

Within an organization, each team, role, decision, and action serves a purpose — whether that purpose is known, clearly understood, and defined or not. For an organization to be effective, it’s important that every purpose people work toward fulfilling contributes to the organization’s overall purpose and is not in contradiction to another purpose elsewhere in the organization. Similarly, and in addition to that, for a team or project to be effective, decisions and actions within a team or a project must also align with that team’s or project’s purpose and must not contradict any other decision or action.

Without such coherence, an organization may face numerous undesirable outcomes, such as conflicting decisions, unclear responsibilities, duplication of effort, or failure to take care of important work.

As an organization grows, complexity increases, and the connection between our interventions — the actions we take and the rules we put in place — and the organization’s overall purpose becomes difficult to track and understand.

Developing and maintaining coherence across this complex, dynamic network of interrelated purposes is both necessary and challenging. It requires ongoing monitoring and evaluation of purposes, interventions, and actual outcomes to ensure that what works is reinforced and what does not is adapted or discarded.

Purpose, Value, and Waste

Understanding this interrelated network of purposes provides a useful lens for evaluating value and waste in organizations. This perspective also makes many practices and ideas from lean production and lean software development immediately applicable for organizations pulling in S3 patterns, such as the Kanban Method or Value Stream Mapping.

In S3, both concepts are explained in relation to purpose:

Value is the importance, worth or usefulness of something for fulfilling a purpose.

Waste, in relation to purpose, is any activity, output, or use of resources that does not contribute — directly or indirectly — to fulfilling that purpose.

There is a wealth of research and development about value and waste in organizations. Exploring these ideas can provide valuable insights and practical methods for improving flow, reducing unnecessary effort, and increasing effectiveness when fulfilling organizational purposes.

How to Describe Purpose: Drivers and Requirements

For familiar or obvious challenges or opportunities, it’s easy to describe purpose because it’s implicit or self-evident. But even in such cases, sometimes we might discover that our interpretations differ from others’, and what we thought was obvious turns out to be more complicated or complex.

In many situations, especially when things are new, uncertain, or complex, our understanding of what’s going on and of what’s required to respond may be more or less clear. Some aspects of a situation might be well understood, while others remain uncertain or entirely unknown. Therefore, it’s helpful to have a way to describe purpose that reflects the clarity we have so far, while leaving space to evolve our understanding over time. This makes it easier to communicate, develop shared understanding, and regularly review and adjust our approach as we learn more.

To help people make sense of and clarify purpose, we use the concepts of Organizational Drivers and Requirements:

- An organizational driver is any situation that is relevant for the organization to address.

- A requirement is a state considered valuable to establish or maintain in order to address a specific driver.

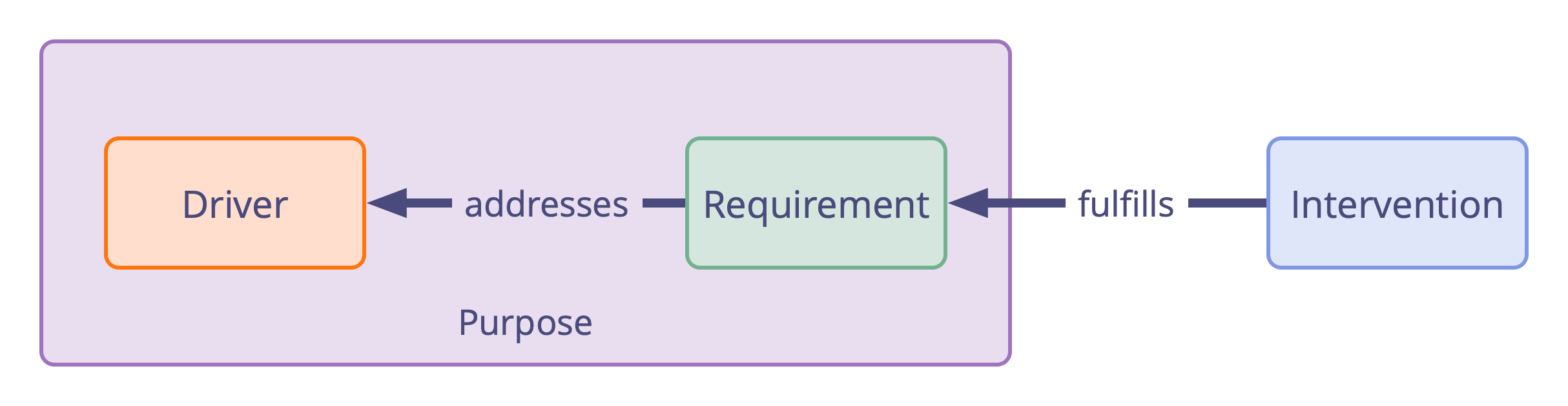

This implies that any intervention that aims to fulfill (or at least serve) a specific purpose can be understood as fulfilling a specific requirement that has been identified as suitable to address a specific situation of relevance. The driver explains the situation that makes the intervention relevant. The requirement serves both as an indication of the direction to go and as a clarification of the scope and boundaries of the intervention.

So describing purpose in terms of a driver and a requirement clarifies why the intervention is needed in the first place, and then helps people understand and decide more specifically what to do. A purpose well articulated and understood not only explains and justifies activity, but it also motivates and drives action.

Organizational Drivers

Identifying and understanding situations that present potential impediments or opportunities in relation to an organization’s objectives is essential for successfully navigating daily work and making the best use of limited resources, energy, and time.

However, not all situations that motivate an organization’s members to act are relevant for the organization to address. The concept of organizational drivers supports people in making this distinction explicit, enabling greater clarity, alignment, and focus, both in deciding what is necessary to respond to and how to respond.

An organizational driver is a situation where the organization’s members have a motive to respond because they anticipate that doing so is beneficial or necessary for fulfilling the organization’s purpose. (by helping generate value, eliminate waste, or avoid undesirable risks or consequences).

Note: In this guide, organizational drivers are often simply referred to as “drivers”.

Organizational drivers do not exist in isolation: in the course of serving the organization’s overall purpose, people encounter numerous organizational drivers: challenges, impediments, risks, and opportunities. Some arise as a consequence of decisions you or others make in the organization, while others are due to external factors or changes. New drivers also often become apparent through the process of breaking down work into smaller parts.

Whenever you identify situations that appear to represent a problem, challenge, impediment, risk, or opportunity for the organization, you are thinking about potential organizational drivers.

Examples of situations that qualified as organizational drivers:

- The team spends 25% of their work hours on admin work, and this is leading to slow response time for customer requests and a growing number of complaints. The organization is starting to develop a bad reputation and runs the risk of losing customers and compromising future sales.

- Teams often work on items that have not been prioritized in accordance with the product roadmap. This slows down the delivery of features that have been assigned a high priority by the customer and is leading to complaints about the effectiveness of the teams’ work.

Making sense of such situations and establishing if they are indeed relevant for the organization to deal with, before deciding how to respond to them, brings several benefits:

- Understanding a situation well is essential for determining what’s required to address it adequately (see Respond to Organizational Drivers).

- Investigating a situation before acting helps avoid mistaken assumptions (see Navigate via Tension).

- Describing a driver is an effective way of communicating with others, ensuring a shared understanding of the situation and why we must act (see Describe organizational Drivers).

- Clarifying why you intend to act helps you evaluate outcomes effectively later and adapt based on learning.

- Recording an organizational driver in its current form also helps with monitoring if the driver changes over time.

See Describe Organizational Driver for more examples.

To determine whether a situation qualifies as an organizational driver, reflect on this question:

Would responding to this situation help the organization generate value, eliminate waste, or avoid undesirable consequences?

- If the answer is yes, the situation qualifies as an organizational driver that requires attention.

- If not, you can disregard it.

- If you are uncertain, investigate further, which might include reaching out to others who have a clearer idea.

Whenever a situation qualifies as an organizational driver, dealing with it needs to be prioritized alongside other work. Even though many situations may qualify as organizational drivers, they might never be addressed because other drivers are more important.

This careful consideration of which situation should be addressed and when helps people stay focused on and responsive to the ongoing flow of challenges and opportunities that arise day to day and that are beneficial to deal with, considering the organization’s various objectives and overall purpose.

While identifying organizational drivers often seems straightforward, be mindful of some common challenges people bump into, both when recognizing potentially relevant situations and when determining whether those situations are, in fact, relevant:

Related to understanding the situation:

- Misreading the situation: People conflate what they observe with how they interpret it.

- Conflicting or incomplete interpretations: People have different perspectives on what is actually happening and cannot reach an agreement, or fail to integrate different perspectives.

- Mistaking symptoms for root causes: Sometimes, the situation you’re reacting to is itself caused by something deeper. Without addressing the underlying cause, the real problem persists.

Related to determining relevance to the organization:

- Lack of awareness: “I didn’t realize it was even a problem”

- Missing context: A lack of understanding of the organization’s overall purpose, strategic direction, values, or existing policies makes it harder to determine what matters.

- Confusing correlation with causation. Sometimes, the situation you are observing is a downstream effect of upstream causes. In complex situations, cause-and-effect relationships are often difficult to determine.

- Confusing correlation with causation: Sometimes, you focus on addressing a particular situation without recognizing that there is an underlying issue that needs to be addressed in order to deal with it effectively.

For more guidance on how to describe organizational drivers clearly and effectively, see the Describe Organizational Drivers pattern.

Note: It’s generally good practice to keep a written record of any significant drivers for future reference or when they need to be communicated. However, there are some cases where recording a driver doesn’t add any value, e.g. in operational day-to-day decisions that don’t have any significant or lasting impact on the organization, or when the driver is implied by a requirement or an intervention that has already been determined (see the section “Define just enough detail to be helpful”).

Related Patterns:

- Describe Organizational Drivers offers guidance on how to describe organizational drivers clearly and effectively.

- Respond to Organizational Drivers explains the steps for responding to organizational drivers.

Requirements

A requirement connects a driver and the intervention intended to address it. It bridges the problem space and the solution space. Once it has been determined to be suitable for addressing a driver, a requirement is binding and sets the scope and direction for the intervention you define. In this sense, requirements function as constraints.

A requirement is a state considered valuable to establish or maintain in order to address a specific driver.

What’s the Benefit of Explicitly Clarifying Requirements?

Unless the way to address a particular driver is obvious, explicitly clarifying the intended outcomes and the enabling conditions you think should be established to achieve those outcomes, before determining more specific solutions, will give you the following benefits:

- Encourages more intentionality: When determining the requirement first, people are more likely to think consciously about how to address a driver, rather than acting based on reaction or habit, especially in novel and or complex situations.

- Clarifies intent and direction: By defining the outcome you seek and the conditions you deem suitable to establish, you anchor the intervention in shared understanding rather than assumption.

- Clarifies scope: The requirement serves as a constraint on the kind of interventions that are acceptable or feasible, narrowing down the pool of options to those that suit the context.

- Creates space for creativity and diverse input: A well-framed requirement invites a broader range of ideas before narrowing in on specific interventions.

- Supports delegation and autonomy: When others will carry out the intervention, clearly stated requirements enable them to act with greater confidence and less oversight while remaining aligned with organizational intent.

- Enables effective collaboration: The requirement provides a common ground for collaborating on finding suitable solutions and helps reduce unnecessary friction from people pulling in different directions because they have different assumptions about what is needed.

- Enables effective evaluation: The outcome provides a reference point for assessing whether an intervention successfully addressed the driver, supporting iterative learning and continuous improvement.

The Anatomy of a Requirement

Determining the requirement involves intentionally and explicitly defining the intended outcome(s) and the enabling condition(s) considered suitable to establish or maintain for achieving that outcome.

In the context of a requirement, intended outcome(s) are specific, observable results you aim to achieve in relation to a driver.

In the context of a requirement, enabling conditions are conditions considered necessary to establish for achieving or maintaining intended outcomes.

Examples of requirements:

- Enabling Condition: We need to store and share relevant information effectively…

Intended Outcome: …to improve everyone’s ability to provide valuable solutions for our customers. - Enabling Condition: We need to free up time to handle customer requirements in a timely manner…

Intended Outcomes: …so that we can improve customer satisfaction and eliminate this type of complaint.

Why Clarify Both the Intended Outcomes and the Enabling Conditions in a Requirement?

- Distinguishes Ends from Means

- The intended outcome represents the future state we aim to realize (the end).

- The enabling conditions describe what we consider suitable and sufficient to achieve that outcome (a means, but not the intervention itself).

- Separating these elements allows for clearer evaluation, adaptation, and learning over time.

- Enables more effective design of the intervention

- The intended outcome defines the direction a suitable intervention must take

- The enabling conditions help narrow the scope of possible interventions to those we find acceptable, and guide discussion and refinement of the intervention’s details.

- Supports evaluation and accountability

- The outcome serves as the foundation for evaluation, as it clarifies what success looks like and allows assessment of whether the intervention helped achieve what was intended.

- The enabling condition provides a basis to evaluate whether the intervention was appropriately scoped and implemented.

Requirements as Assumptions that Guide Iteration and Learning

When determining a requirement in relation to a driver, we make several discrete assumptions:

- Our understanding of the driver is accurate and sufficient for determining a suitable requirement

- The intended outcomes are achievable and valuable (in relation to the driver)

- The enabling conditions we want to establish (or maintain) are suitable and sufficient for achieving that outcome

These assumptions are based on the information available at the time, as well as the level of understanding and experience we have about the situation we are dealing with. Any of these assumptions may be wrong. Therefore, requirements need to be tested, monitored, and, if necessary, changed over time.

When interventions are implemented as designed but don’t work as expected, being able to revisit both outcomes and enabling conditions separately helps determine what needs to be improved:

- The design of the intervention is flawed: we implemented the intervention, but it didn’t establish the enabling conditions, and also did not achieve the intended outcomes.

- The assumed conditions are inappropriate or insufficient for achieving the intended outcomes: the enabling conditions were met, but it didn’t lead to the outcome we intended.

- The intended outcomes are unsuitable: we achieved the outcomes we intended, but the driver was not adequately addressed.

- The intended outcomes are unattainable: they have not been achieved, and it appears unrealistic to expect they can be achieved in this context.

Revisiting these elements will help determine how to evolve your approach:

- If necessary, update your understanding of the driver.

- Then review, and if necessary, update the requirement.

- Finally, adapt the intervention itself.

When and Why to Make Requirements Explicit

We often make interventions to address organizational drivers based on our assumptions about the requirement, without making those assumptions explicit. This isn’t necessarily a problem, especially in familiar situations, where established patterns work well.

However, in novel or complex situations, jumping too quickly to a specific intervention can be detrimental. Our habitual or automatic responses may not suit the situation, leading to unintended consequences and missed opportunities for a more fit-for-context response.

Example:

You receive an email inquiry from a potential client. It seems straightforward, so your instinct is to reply quickly and informatively to acknowledge them and provide the information requested.

Requirement (habitual): Respond promptly and informatively to maintain professionalism and client satisfaction.

However, upon closer inspection of the email, you realize the inquiry references a possible collaboration involving a major strategic opportunity, not just a routine question.

Requirement (deliberate): Formulate a thoughtful and tailored response that opens a conversation and increases the likelihood of strategic collaboration.

By resisting the urge to respond habitually and instead clarifying what is actually required, you significantly improve the chances of securing a high-value partnership — something a quick, generic reply might have missed.

This comparison illustrates how a more deliberate process for determining the requirement can better ensure a strategic and impactful response.

Organizations often put emphasis on an action-oriented or solution-oriented mindset. However, in collaborative settings, focusing on specific interventions too early — before we fully understand the requirement — can stifle creativity and lead to unnecessary tension or conflict.

Moreover, interventions may sometimes stem from individuals projecting past experiences onto the current situation or simply defaulting to familiar routines. This can result in actions that do not adequately address the driver. A more suitable approach is first to determine a suitable requirement and then establish an appropriate intervention to fulfill it.

Note: In complex situations, it may not be possible — or even useful — to determine a single overall requirement that fully addresses the driver at the outset of responding to it. However, it is always possible to identify a requirement that serves as a valuable next step in addressing the situation. This “sub-requirement” is already part of the intervention itself (see the section on Interventions below for more details). In such cases, you can mark the overall requirement as “TBD” (to be determined) and update it as your understanding evolves. In these situations, it is entirely valid to incrementally fulfill any sub-requirements you are able to determine as suitable, either until the overall requirement becomes clear or until the driver is sufficiently addressed through the interventions taken.

Requirements and User Stories

The concept of requirements in S3 is closely aligned with how the term is used in software engineering, where a requirement describes a capability or condition needed to fulfill a purpose. S3’s concept of requirements provides a more generalized structure to support more deliberate and adaptive decision-making across a wide range of organizational contexts and beyond.

In software development, user stories are one way of describing requirements, typically focusing on user needs and outcomes in a concise, conversational format. A slight adaptation of this format also lends itself well to expressing requirements in S3:

User stories are formulated as follows:

As a <role> I want <capability>, so that <value>.

The equivalent in our model is:

(Considering the driver) we need <enabling condition>, so that <intended outcome>.

While a user story is written from the perspective of a customer or end user, a requirement in this context is typically written from the perspective of the organization responding to the driver — or a subset of its members — so the <role> is simply inferred from the driver. As with user stories, the details of the enabling conditions or intended outcomes may emerge over time. Requirements are formed through conversation, and refined collaboratively — ideally close to the time the driver is to be addressed — and then improved iteratively based on actual outcomes and learning.

Connecting requirements to their underlying drivers deepens shared understanding and strengthens alignment around what matters most. In the same way, it’s often beneficial to make the driver behind a user story explicit, as it provides additional context to help the developer better understand the customer’s (or user’s) needs.

Related Patterns:

The Relationship Between Driver and Requirement

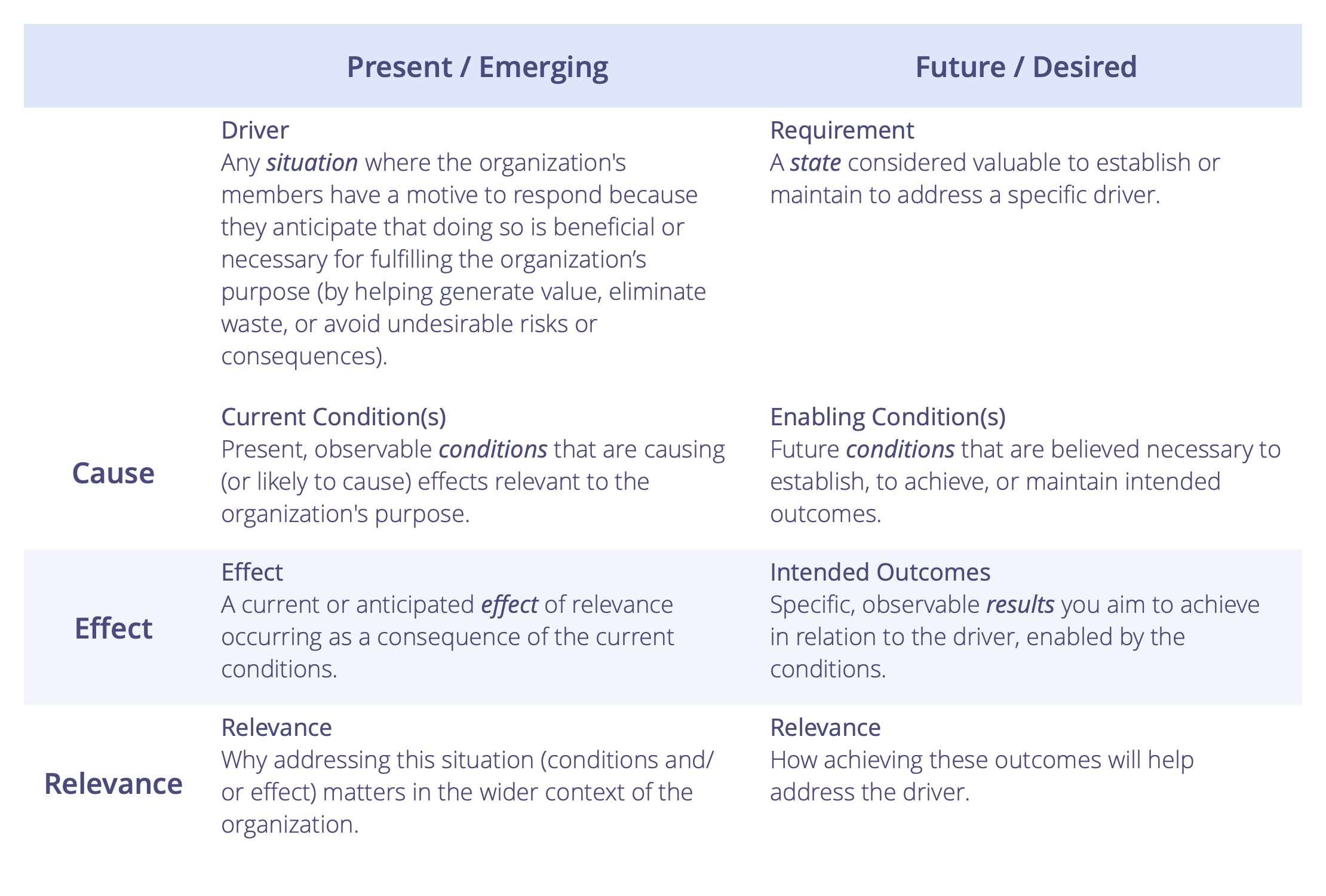

The following table highlights the structural parallels between drivers and requirements and clarifies how they relate.

Both concepts represent states in a system, yet they occupy distinct positions in the logic of purposeful action: a driver is a situation in the present that requires attention, and a requirement is a future situation whose realization is expected to address that driver.

The distinction mirrors a broader pattern: each present-focused element (current conditions, effects, relevance) has a corresponding future-focused counterpart (enabling conditions, intended outcomes, relevance). Together, these pairs help clarify both why action is needed now and what is believed necessary to move toward a preferable state.

Interventions: Turning Purpose into Action

The model of purposeful action rests on the observation that work in organizations can be understood as people making interventions to fulfill a purpose.

Now that we’ve clarified what purpose is and how it can be described in terms of drivers and requirements, the next step is to explain more about the nature and structure of interventions. After all, interventions are how people translate purpose into practice — they are the only means through which organizations create and deliver value: it’s interventions that ultimately pay the bills.

An intervention is the specific steps you take and/or the constraints you put in place to fulfill a purpose.

Interventions represent the means by which people fulfill purposes in practice. Depending on the specific purpose an intervention is intended to fulfill, it may be a simple operational task or a rule put in place to guide decisions and actions. However, interventions can also involve a complex arrangement of activities, prescriptions, constraints, and recommendations.

Some interventions are informal and intuitive, while others are developed intentionally, either by individuals or collaboratively by groups, and may require careful coordination, documentation, or evaluation. In complex situations, taking an experimental approach and developing interventions iteratively and incrementally is worthwhile.

Examples of Interventions

Interventions include both simple one-time tasks and longer-term activities or constraints that guide ongoing decisions. For example:

- Create an agenda for a meeting

- Responding to a customer inquiry

- Reviewing financial data

- Set a time box for a meeting

- Priority order of tasks or agenda items

- Assigned responsibility for specific tasks or roles

- Define the scope of work and decision-making authority for a role or team

- Define a standard operating procedure

- Set a budget limit or spending cap

- Define a strategy

- A policy for onboarding new members of the organization

Interventions That Constrain

Interventions not only refer to what to do (tasks, activities) but also may include putting limits on how things must be done or on the behaviour of members of the organization. We refer to these limitations as constraints:

A constraint is a limitation or restriction that controls or limits what someone can do or what can happen. It can be a requirement to fulfill, a rule to follow, or a boundary on actions, behaviors, or outcomes.

You will find constraints in organizational strategy, policies, organizational values, and priorities, as well as all implicit expectations about what people can and cannot do (“unwritten rules”).

Note: In the course of designing an intervention, any sub-requirement deemed suitable for contributing toward fulfilling the main requirement is, by definition, binding and therefore also functions as a constraint. However, this section is not concerned with sub-requirements; it focuses on interventions that, by themselves, impose constraints on behavior and activity in other parts of the system.

In the context of interventions, constraints are not restrictive in a negative sense. Rather, they serve to support collaboration, reduce friction, prevent waste, and help people make decisions that are aligned with the organization’s broader purpose and objectives.

Constraints can apply to specific tasks or activities, guide behaviour, or limit the range of choices available when making decisions. They can be implied in a requirement or task (e.g., when the task is assigned to somebody), or made explicit, and may be as simple or detailed as necessary.

Examples of constraints:

- A time box for a meeting

- Priority order of tasks or agenda items

- Assigned responsibility for specific tasks or roles

- Defined scope of decision-making authority

- A standard process or template for certain situations

- A budget limit or spending cap

- Expected response times for internal communication

In practice, tasks, activities, and constraints are often described together, e.g., when a list of tasks also includes to whom that task is assigned, or under which specific or recurring conditions a task has to be executed.

Understanding the Flexible Nature of Interventions

In the daily work of an organization, interventions span a broad range from small, targeted adjustments to complex arrangements of activities and constraints. Some require little thought or coordination, while others call for careful planning, collaboration, and adaptation over time.

In many cases, interventions can be described as a single task or a single constraint. In other cases, it’s necessary to describe an intervention in more detail and break it down into a number of tasks, activities, and constraints, each of which contributes toward fulfilling the purpose.

Also, the process of describing tasks, activities, or constraints often brings new situations of relevance or requirements into focus, which in turn may require more tasks, activities, or constraints.

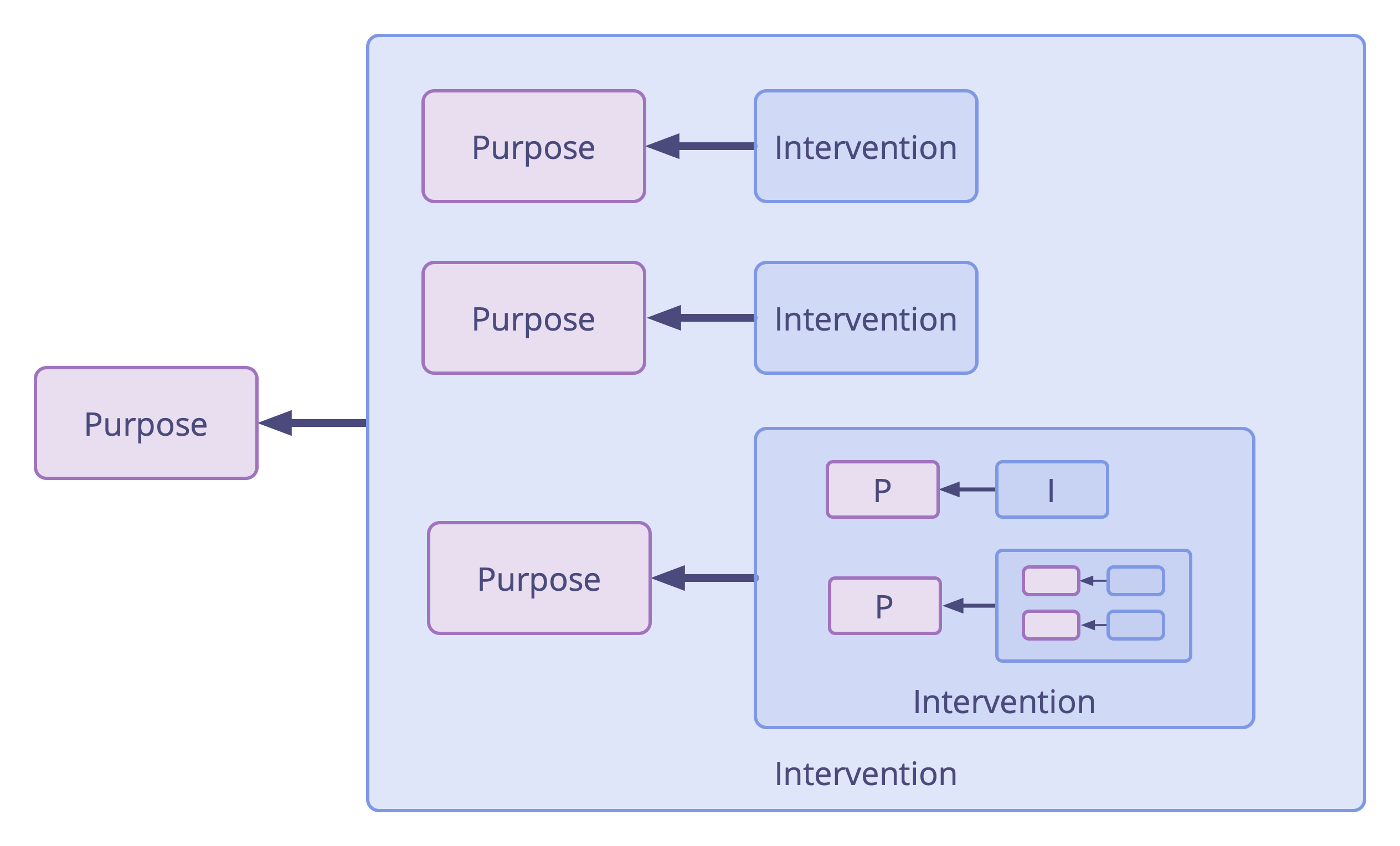

In that context, it is helpful to imagine an intervention as a nested structure of sub-interventions, over as many layers as is necessary to convey what needs to be done or constrained.

This flexible structure of interventions lends itself to an iterative approach, because interventions can be broken down into smaller parts (sub-interventions) over as many levels as needed, and it’s simple to add, replace, or restructure elements as understanding of the situation and requirement evolves or the situation changes.

Following the model for purposeful action, there is a specific purpose (driver and requirement) for each of those sub-interventions. This recurring pattern of purpose and intervention reflects the complexity of organizational life: activities at one level of detail often reveal new drivers, requirements, and corresponding interventions at another.

Breaking down a more comprehensive intervention in this way is especially helpful when it involves:

- Multiple stakeholders or contributors

- Recurring activities (systems of tasks and perhaps constraints)

- Dependencies that must be taken into account

- New members of a team or organization who are unfamiliar with how things are done

- People who are less experienced in implementing the intervention.

While each of these sub-interventions ultimately contributes toward fulfilling the overall purpose of the intervention, some of them arise as a consequence of dependencies with other parts of the organization, or wider adherence to constraints within the organization or its broader environment within which it operates.

In many cases, these dependencies are already present but only become salient when people begin acting on a requirement. Making them explicit can help maintain coherence, especially when coordination across teams is required.

Note: an intervention — or one of its parts — may contribute to fulfilling several different or related purposes, especially in the case of dependencies between individuals or teams. In such cases, use your best judgment to decide whether the intervention needs to be tracked or referenced in all relevant contexts, or whether it is sufficient to document and monitor it in a single place, with links or references as needed.

Define Just Enough Detail to Be Helpful

Thinking through and defining interventions doesn’t require exhaustive detail. Use your best judgment about what to include and what to omit. It’s good practice to leave out obvious or redundant elements and to leave undefined those aspects that the people responsible for implementation are better able to determine, based on their context or evolving situations.

Interventions frequently include one or more activities along with constraints relating to those activities, such as who’s responsible, due dates, or other important conditions. One entry in such a list might look like this: “Sally will compile a report by Friday.” Presented together, they form a clear and useful description of the intervention, combining the activity itself (compile the report) and two constraints (who will do it and by when), each of which corresponds to an implicit sub-requirement.

In cases where fulfilling a requirement is so simple, obvious, or familiar that it directly implies what a suitable intervention would be, there is no need to spell it out explicitly. For example, if the requirement is to “Inform people about the topics for tomorrow’s meeting so they arrive prepared,” describing the intervention (“prepare and send out the agenda today”) may be unnecessary.

The same can be true for more complicated or complex interventions if the people responsible already share a clear and sufficient understanding of what needs to be done and why.

Example:

Driver: The product unexpectedly went offline, negatively impacting users and posing a risk to customer satisfaction and retention.

Requirement: We need to restore trust and satisfaction among affected customers so that we maintain a positive relationship with them and they continue using our product.

For an experienced support team, the requirement provides enough information to successfully fulfill it.

However, sometimes explicitly naming the intervention and/or breaking it down into smaller steps helps evaluate the effectiveness of the various steps, or for ensuring adequate understanding, especially among people with less experience in the matter or new to the organization.

When breaking interventions down into smaller parts (sub-interventions), the purpose (or rationale) for each part is often implicit, since the context remains within the scope of the main purpose and usually doesn’t need to be restated.

However, be mindful of situations where it’s worthwhile to clarify the purpose of certain parts — especially when there’s a reason something needs to be done in a particular way, or when sub-interventions need to happen in a certain order or are otherwise interrelated. Likewise, if parts of an intervention relate to the wider organization — such as org-wide policies, responsibilities, or dependencies — or to the external environment, document this explicitly.

To clarify the purpose of a sub-intervention, it can be enough to define only the enabling conditions that need to be established — especially when the higher-level outcome is already clear — or just the intended outcomes, if this implies what enabling conditions are needed. In other cases, it’s useful to describe the situation (driver) that the requirement is meant to address.

Example:

Continuing from the example above regarding the fallout from the product unexpectedly going offline, as part of the overall intervention, the team chose to send everyone an email. However, they also identified one customer who had a particularly negative experience and thought an email would be inadequate in this case. Depending on their context, for that sub-intervention, they might define and document one or more of the following:

- Sub-Intervention: Call customer X to check in and offer support.

- Enabling Condition: The customer feels heard and supported.

- Intended outcome: The customer stays.

- Driver: Customer X had a negative experience when the product went down, expressed dissatisfaction, and threatened to leave.

In some cases, when designing interventions, it can be adequate first to determine sub-requirements you consider suitable to fulfill in the course of fulfilling the main requirement, deferring more specific decisions about how to fulfill some or even all of those sub-requirements until later. For example, you might decide that “participants have access to relevant information,” “there is a clear way to raise concerns,” and “facilitation is available when needed” are essential sub-requirements for a productive decision-making process (main requirement), without yet specifying how to achieve this.

Policies: A Specific Kind of Intervention

Policies are discussed in more detail in the chapter about Governance, Operations, and Policy, but a brief introduction is helpful in the context of the model.

Through the lens of this model, policies are simply those interventions that have a significant impact on the organization because they guide decisions and actions repeatedly, or their influence sustains over an extended period of time.

Policies often take the form of processes, procedures, protocols, plans, strategies, or guidelines.

Because of their significance and their long-term use, and because of people’s increasing understanding of the purpose they’re responding to, policies are typically evaluated and evolved over time to ensure they become and remain fit for purpose, even in the face of changing circumstances.

Apart from their significance, there is no difference between a policy and any other intervention: they are created to fulfill a specific purpose, and are composed of tasks, activities, and constraints.

Determining Interventions

Once there is sufficient clarity around the purpose, the next step is to determine a suitable intervention to fulfill it. This involves identifying what needs to be done (tasks and activities) and what constraints need to be put in place to achieve the intended outcomes, at a level of detail appropriate for guiding effective action and evaluation.

If the action to take is already obvious, or if an existing policy already describes what to do, people can often proceed without further elaboration. This happens when simply replying to an email, responding to a customer inquiry, fixing a simple error in code, replacing a defective part on the line, or following a set of predetermined steps in a standard procedure.

In other cases, it may be necessary to take a moment to identify all the steps involved, clarify their sequence, and determine who is best placed to carry each one out.

However, in novel or complex situations, and especially in cases where the main requirement itself is not clear yet, determining a suitable intervention often requires more effort and can involve an iterative approach of investigation, experimentation, and adaptation.

The flexible structure of interventions lends itself to an iterative approach, because interventions can be broken down into smaller parts if helpful, and it’s simple to add, replace, or restructure elements as understanding of the situation and requirement evolves or the situation changes.

So, in such cases, instead of attempting to define the intervention in full from the outset, it is a more viable approach to define only the most useful next step(s) for those sub-requirements that are already apparent. This often includes one or several of the following activities:

- A deeper analysis of the situation to clarify assumptions, surface relevant information, or reveal constraints and opportunities that affect what interventions are possible.

- Reviewing any existing agreements, policies, organizational values, or external constraints that guide or limit possible interventions.

- Identify possible dependencies with other parts of the organization, to avoid impediments, or impeding the work of others, or double work.

- Researching existing patterns, practices, or proven approaches that have worked in similar situations.

- Consulting with others to benefit from diverse perspectives, relevant expertise, or local knowledge.

- Exploring possible options, and selecting one that is safe enough to try and fits the context.

- Testing ideas through small experiments or prototypes before committing to a more substantial intervention.

- Evaluating an intervention on a regular basis and using what has been learned to evolve the intervention as necessary.

You can use the following patterns to determine and evolve interventions:

- Proposal Forming and Co-Create proposals for co-creating solutions based on collective input.

- Consent Decision Making — for surfacing and addressing objections against a possible intervention before implementing it.

- Evaluate and Evolve policies to support continuous learning and improvement of interventions over time.