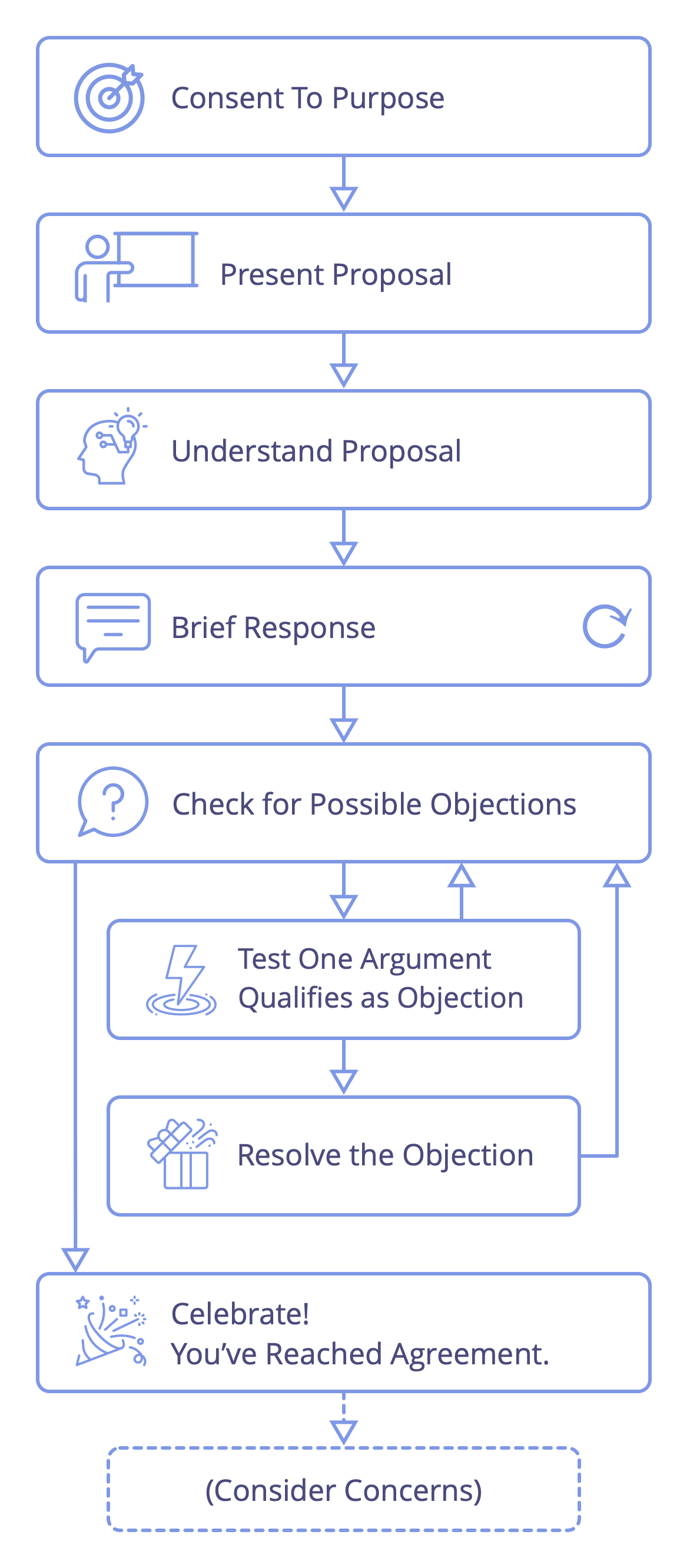

Consent Decision-Making

Table of Contents

- Overview

- Step 1: Consent to Purpose

- Step 2: Present the Proposal

- Step 3: Understand the Proposal

- Step 4: Brief Response

- Step 5: Check for Possible Objections

- Step 6: Test One Argument Qualifies as Objection

- Step 7: Resolve the Objection

- Step 8: Celebrate!

- Step 9: Consider Concerns

Overview

Consent invites people to (at least) be reasonable and open to opportunities for learning and improvement. When you apply the principle of consent, you are agreeing to intentionally seek out objections.

An objection is an argument – relating to a proposal, existing decision, or activity being conducted by one or more members of the organization – that reveals consequences or risks that are preferably avoided for the organization or that demonstrates worthwhile ways to improve.

Proposals are accepted when they are considered good enough for now and safe enough to try until the next review. Objections prevent proposals from becoming become policy, but concerns do not.

Withholding objections can harm the ability of individuals, teams, or the whole organization to achieve their objectives.

Not all arguments raised are objections, but they might reveal concerns:

A concern is an assumption that cannot (for now at least) be backed up by reasoning or enough evidence to qualify as an objection to those who are considering it.

The most common use case for Consent Decision-Making is when groups need to decide on a policy or other significant decisions, and that is how it is laid out below. However, this process can be used anytime two or more people are working together to make a decision.

If you are new to using Consent Decision-Making, we recommend you strictly follow the process until you become familiar with the rationale behind the steps. As you gain experience, you might skip steps or hop between them, but doing so in the beginning can lead to confusion and even chaos. For example, if there is a general expression of concern voiced during the Brief Response round, it might appear to make sense to evolve the proposal on the spot to include points that people inferred. For any suggestion that involves changing the process, always check if there are any objections to doing so first.

Step 1: Consent to Purpose

Ensure the purpose of the proposal is clear and relevant for the organization (the driver and requirement are summarized clearly enough), and it is your responsibility to deal with this.

Facilitator asks: Is the description of the situation and requirement clear enough? Is this situation an organizational driver? Is this driver relevant for you to respond to? And, is this requirement suitable?

Note: As a general recommendation, aim to complete this step with meeting attendees asynchronously, before the meeting. This will give you the opportunity to make any refinements in advance and save precious meeting time. However, in a case where someone is presenting a proposal to a group of stakeholders who were not involved in creating it, or if there are people who are only now joining the decision-making process, check everyone understands the driver and requirement for the proposal, and ensure they are described clearly enough, the requirement is considered to be suitable, and it’s relevant for those present to deal with this, before considering the proposal itself.

- If the driver is not described clearly enough, take time to clarify and make any necessary changes to how the driver is summarized until there are no further objections. Unless this will be a quick fix, consider doing this after the meeting and defer considering the proposal, until the driver is clear.

- If the driver is not relevant for this group, pass it on to the appropriate person or team, or, if it’s decided that this is not an organizational driver at all, discard it.

- If the requirement is considered to be unsuitable, hear the argument(s), and if they qualify as objections, resolve them before considering the proposal.

Step 2: Present the Proposal

Share the proposal with everyone.

Facilitator asks the author(s) of the proposal: Would you please present the proposal to everyone?

The author(s) of the proposal (when using Proposal Forming, thetuners) present it to the group, including details about who is responsible for what, a suggested review date or frequency, and any identified evaluation criteria.

Preparation: Send out the proposal in advance of the meeting (whenever possible) so that people can familiarize themselves with the content, ask any clarifying questions, or even share improvement suggestions before the meeting. This saves taking up precious face-to-face meeting time for things that can be done outside of the meeting.

Proposals are typically created by an individual or a group beforehand, but are sometimes suggested on the fly.

If you’re the one presenting a proposal, write it down, share it with the others beforehand if possible, and aim to keep your explanation concise and clear. Describe it in a way that maximizes the potential that others will understand what you are proposing, without requiring further explanation.

Note: Involving stakeholders in the creation of a proposal can increase engagement and accountability for whatever is decided because people are more likely to take ownership of a policy that they participate in creating. On the other hand, participatory or collaborative decision-making requires people’s time and effort, so use it only when the gains are worthwhile.

Step 3: Understand the Proposal

Make sure everyone understands the proposal.

Facilitator asks: Are there any questions to understand this proposal as it’s written here?

This is not a moment to get into a dialogue about why a proposal has been put together in a certain way, but simply to check that everyone understands what is being proposed. Avoid “why” questions and focus instead on “what do you mean by …” questions.

Clarifying questions sometimes reveal helpful ways to change the proposal text to make it clearer. You can use this time to make edits to the proposal if it supports people’s understanding, but be wary of changing what is actually being proposed at this stage.

Note: If the group is experienced with using Consent Decision-Making, you may opt to make improvements to the proposal at this stage. However, if you’re less familiar, beware, you are very likely to slip into another session of tuning the proposal, this time with everybody being involved. You run the risk of wasting time attempting to reach a consensus instead of proceeding with the process and evolving the proposal based on objections (in step 7).

Tips for the Facilitator:

- Use a round and invite the tuners (or whoever created the proposal) to answer one question at a time.

- Pick up on any “why” or “why not” questions and remind people that the purpose of this step is simply to ensure understanding of the current proposal and not why the proposal was put together in this particular way.

Tips for everyone:

- Say “pass” if you don’t have a question or if you’re unclear at this point about what your question is.

- Keep your questions and answers brief and to the point.

- Avoid preamble and stick to the point, e.g., “Well, one thing that is not so clear to me, or at least, that I want to make sure I understand correctly is …” or “I’m not sure how to phrase this, but let me try,” etc.

Step 4: Brief Response

Get a sense of how this proposal lands with everyone.

Facilitator asks: What are your thoughts and feelings about the proposal?

Hearing everyone sharing their reflections, opinions, and feelings about a proposal helps to broaden people’s understanding and consider the proposal from various points of view.

People’s responses can reveal useful information and might already reveal concerns or possible objections. At this stage, listen but avoid interacting with what people say. This step is just about seeing the proposal through each other’s eyes.

Examples:

- “I like that it’s simple and straightforward. It’s a great next step.”

- “I’m a bit concerned that this will take a lot of time when there are other important things that we need to take care of, too.”

- “I think there are some essential things missing here, like A and B, for example.”

Tips for Facilitator:

- Invite a round.

- Specify how “brief” the “brief response” should be! This will depend a lot on context and may range from a single sentence to some minutes of each person’s time.

Tips for everyone:

- Avoid making comments or responding to what people share.

- Adjust your contribution to fit the time constraint.

- It’s valuable to hear something from everyone in this round, so avoid passing. If you’re lost for words, you can still say something like, “I need some more time to think about it,” or “I’m unsure at this point where I stand.”

Step 5: Check for Possible Objections

People consider the proposal and then indicate if they have possible objections or concerns.

This step is simply about identifying who has possible objections or concerns. Arguments are heard in the next step.

If you came here from step 7 (Resolve One Objection), check for further possible objections to the amended proposal.

The facilitator asks: Are there any possible objections or concerns to this proposal?

Remember: concerns don’t prevent proposals from being accepted; only qualified objections do. Concerns are heard in Step 9 after celebrating reaching an agreement!

Tips for the facilitator:

In case the distinction between objections and concerns is still unclear for some people, remind them:

An objection is an argument – relating to a proposal, existing decision, or activity being conducted by one or more members of the organization – that reveals consequences or risks that are preferably avoided for the organization or that demonstrates worthwhile ways to improve.

A concern is an assumption that cannot (for now at least) be backed up by reasoning or enough evidence to qualify as an objection to those who are considering it.

Tips for everyone:

- Many groups use hand signs as a way to indicate quickly and clearly if anyone has any possible objections or concerns. If you are new to the process and concerned that you may be influenced by each other, wait until everyone is ready and then show hands simultaneously.

- If you are in doubt between a possible objection or a concern, share it as a possible objection so that you can check with others to test if it qualifies.

If no one indicates having any possible objections, you have reached an agreement. Move on to step 8 (Celebrate)!

Step 6: Test One Argument Qualifies as Objection

Use your limited time and resources wisely by testing if arguments qualify as objections and only acting on those that do.

Typically, it’s most effective to take one possible objection at a time, test if it qualifies as an objection, and, if it does, resolve the objection before moving on to the next argument.

Tip for the Facilitator: In case there are several possible objections, explain to everyone that you’re going to choose one person at a time to share one argument. Clarify with everyone that, having heard the argument, if someone believes it would be more effective to consider one of their arguments first, they should speak up.

Check that the argument reveals how leaving the proposal unchanged:

- leads to consequences you want to avoid,

- could lead to consequences you wish to avoid, and it’s a risk you don’t want to take,

- or informs you of a worthwhile way to improve how to go about achieving your objectives.

See the pattern Test Arguments Qualify as Objections for more details.

If the argument doesn’t qualify as an objection, go back to step 5 (Check for Possible Objections). Otherwise, continue to the next step.

Step 7: Resolve the Objection

Improve the proposal based on the information revealed by the objection in the previous step.

See pattern Resolve Objections for details.

Once the objection is resolved, return to step 5.

Step 8: Celebrate!

Amazing! You reached an agreement! And, with practice, you’ll get faster as well! Take a moment to acknowledge the fact that an agreement has been made. Celebrate!

Step 9: Consider Concerns

After celebrating, consider if any concerns you have are worth voicing to the group before moving on to the next topic. If not, at least record them after the meeting, alongside the evaluation criteria for this policy. Information about concerns might be useful for informing the evaluation of the policy.

Facilitator asks those with concerns: Are there any concerns worth hearing now? If not, please at least ensure that they are recorded alongside the evaluation criteria for this policy.

Sometimes, what someone thought was a concern turns out to be an objection. In this case, you can resolve it by amending your just-made policy using Resolve Objections.