Determine Requirements

Table of Contents

- Why Determine Requirements?

- When to Determine a Requirement?

- How to Describe a Requirement?

- How to Determine a Requirement?

- Clarifying Requirements Through Acceptance Criteria

- Keep a Record

Determining a requirement before deciding on the specific steps to be taken helps define a general direction and scope for an intervention, while still allowing for a range of options on how to fulfill the requirement to respond to the driver in an effective way.

As we mentioned in the section A Model for Purposeful Action one way to understand work in organizations is as people making interventions to fulfill a purpose.

Purpose informs, motivates, and guides action. Interventions are specific steps people take, and/or the constraints they put in place, to fulfill a purpose.

To help people make sense of and clarify purpose, we use the concepts of organizational drivers and requirements.

- An organizational driver is any situation that is relevant for the organization to address.

- A requirement is a future state considered valuable to establish or maintain in order to address a specific driver.

- The intervention can be understood as fulfilling the requirement that has been identified as suitable to address the driver.

In short, the driver explains the situation that makes the intervention relevant. The requirement serves both as an indication of the direction to go and as a clarification of the scope and boundaries of the intervention.

Usually, the people responsible for addressing a driver are also responsible for determining the corresponding requirement. In more complex situations, it can be helpful to involve people with diverse perspectives when determining the requirement, because they can surface blind spots, challenge assumptions, and improve shared understanding — leading to a clearer, more realistic, and more widely supported requirement.

Why Determine Requirements?

When people notice a problem or opportunity, there’s a natural tendency to jump straight to an intervention (“let’s do X”). That speed can be valuable, but it can also lead to avoidable problems: people might act on habits that are unsuitable for the current context, or they might overlook constraints and side effects, or end up in polarized conversations about what to do before they even agree on which direction to take.

Determining a requirement, before deciding on specific steps to take or constraints to put in place, defines a general direction and scope, while still allowing for a range of options on how to fulfill the requirement.

When two or more people share responsibility for deciding how to address an organizational driver, differing opinions about specific solutions can lead to contention. When stakeholders are on the same page about the requirement, agreeing on an intervention becomes much easier: proposals can be compared against a shared “target condition,” rather than against competing opinions.

Even if you are the sole person responsible for responding to an organizational driver, it’s useful to clarify the requirement for yourself before deciding how to proceed. Deciding on a course of action is often more straightforward when the general direction and scope for such action are determined first.

When to Determine a Requirement?

Determine a requirement after confirming that the situation you wish to address qualifies as an organizational driver, and that it’s your or your team’s responsibility to deal with it.

Avoid determining requirements for situations you don’t plan to tackle soon, because context and relevance can change, and your efforts might go to waste.

Before investing time in determining a suitable requirement, consider whether there is already a policy in place that covers this kind of thing. Also, check if you already have a policy in place that you can adapt or extend to address this situation.

Even in the case that a suitable requirement is obvious (to you), it’s still often worthwhile to make it explicit by recording it for future reference.

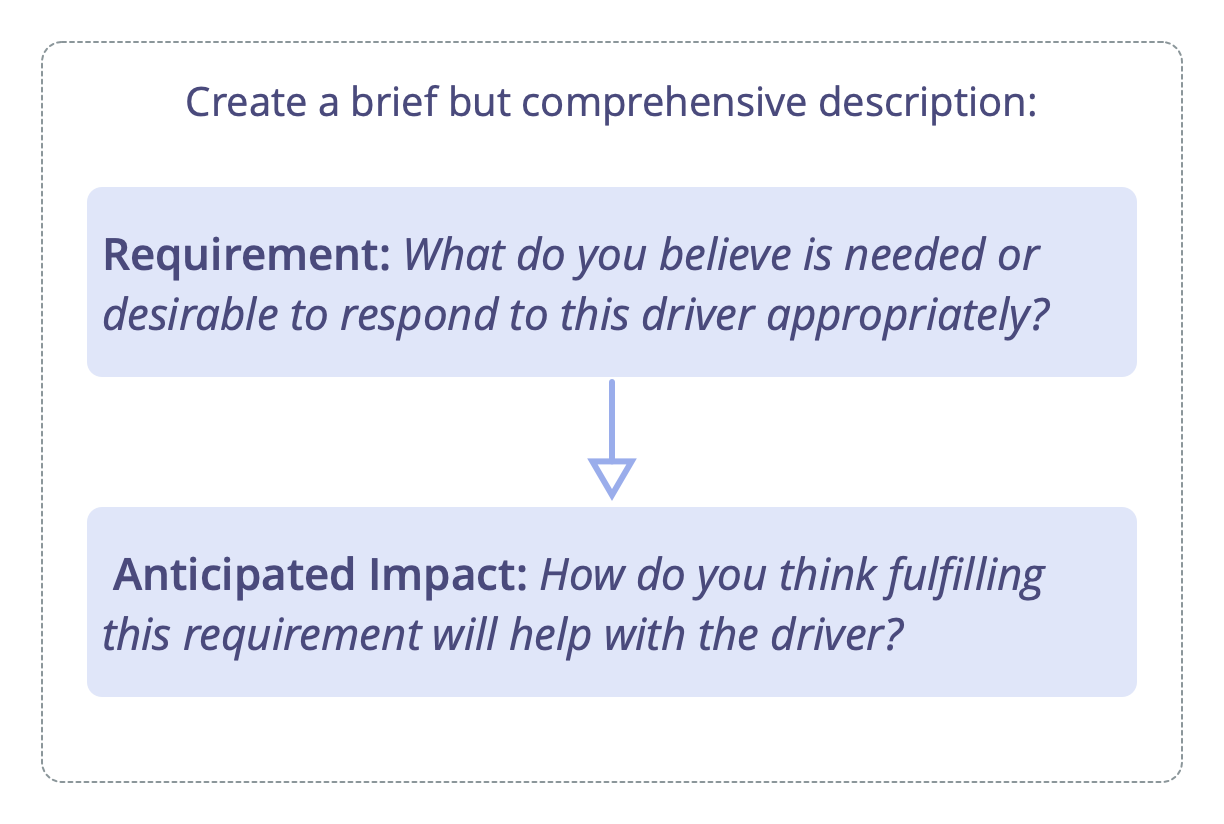

How to Describe a Requirement?

An organizational driver is a present situation that the organization would benefit from addressing. A requirement linked to a driver is a desired future state, in which the present situation is adequately addressed. The requirement defines direction and scope for a suitable intervention.

A simple way to describe a requirement is by explaining:

- Intended outcome(s): Specific, observable results you aim to achieve in relation to a driver.

- Enabling condition(s): Circumstances considered necessary to establish or maintain for achieving or sustaining the intended outcomes.

How much detail is necessary to communicate a requirement depends on context. For simple requirements, it is sufficient to explain them as a single sentence:

<stakeholder> needs <enabling conditions> so that <intended outcomes>.

Examples

- (stakeholder) Employees need (enabling conditions) to gain confidence and competence in applying the new procedure so that (intended outcome) they can carry out their responsibilities independently without needing frequent guidance or correction.

- (stakeholder) We (enabling conditions) need to ensure that team members’ concerns about how we work are heard and addressed (intended outcomes), so that we can address issues early and prevent bigger problems down the line.

- (stakeholder) We (enabling conditions) need to understand recurring themes and patterns in customer feedback (intended outcome) to prioritize necessary and worthwhile improvements.

People familiar with Scrum or other agile methodologies will recognize that the format above is similar to that used for user stories. We use it deliberately: the concept of a ‘requirement’ builds on the idea of user stories, and extends it beyond product development to apply to any kind of purposeful intervention, in organizations and beyond. (see Requirements and User Stories

Often, the stakeholder is implicit, and sometimes it’s only necessary to describe the intended outcomes, or only the enabling conditions, because the other is obvious or implicit.

Examples (variations on one requirement):

- (enabling conditions) Gain confidence and competence in applying the new procedure (intended outcome) so that everyone can carry out their responsibilities independently without needing frequent guidance or correction.

- (stakeholder) Everyone (intended outcome) needs to be able to carry out their responsibilities independently without needing frequent guidance or correction.

- (stakeholder) Employees (enabling conditions) need to gain confidence and competence in applying the new procedure.

How to Determine a Requirement?

A requirement is always determined in relation to a driver, so before doing so, make sure the driver is understood. Write down a description of the driver to keep it in mind.

If the requirement is obvious, name it and go on. There is no need to overthink something if it is known or clear.

Otherwise, start by identifying outcome(s) that are valuable in relation to the driver, and then identify the immediate condition(s) that must be true to realize those outcomes.

- Which outcomes would be valuable in addressing the situation?

- Which enabling conditions need to be in place to achieve these outcomes?

When determining requirements, it’s important to ensure that existing external or standard constraints are considered. Many of these will be considered implicitly during the process, because people already have them in mind, and they naturally shape what they judge to be an appropriate requirement.

After defining a combination of outcome(s) and enabling condition(s), check if the resulting requirement is suitable, effective, and feasible:

- Suitability: Will the outcome address the driver?

- Effectiveness: Are the enabling conditions likely to produce the outcome?

- Feasibility: Can the conditions realistically be established?

Refine the outcomes and enabling conditions (using objections if seeking others’ opinion) until the requirement is good enough.

If even after some deliberation, the full requirement is still not apparent, identify a requirement for the next incremental step. Once that step has been implemented, return to defining the complete requirement.

Note: If you discover later that a requirement turns out to be unsuitable, ineffective, or unfeasible, refine it as needed or start from scratch and determine a new requirement.

Requirements in Complexity

When dealing with a complex situation, the relationship between cause and effect is unclear, and there might be many unknown unknowns.

Further investigation of the situation or experimentation to test assumptions may be the first requirement, and fulfilling that will lead to the emergence of more specific requirements. This process of iteratively defining requirements and then fulfilling them continues until the situation is adequately addressed.

In complexity, it’s also useful to determine requirements collaboratively, to benefit from the diversity of perspectives and experiences of relevant stakeholders or others with expertise.

Balancing Specificity and Scope

When determining a requirement, make a conscious decision about how specific or broad it should be. Each requirement inherently suggests a direction for the intervention that addresses the organizational driver; a more specific one narrows the range of options, while a less specific requirement broadens the possibilities. The desirability of a wider or narrower scope of options varies depending on the situation.

Contradictory suggestions about what is required often indicate that the discussion could have become overly specific. In that case, zooming out to a higher level that encompasses these suggestions can open the way for a broader range of options for designing an intervention.

Clarifying Requirements Through Acceptance Criteria

While a requirement can often be described sufficiently with a single sentence, there is sometimes merit in defining it further. This is especially the case when it would otherwise be difficult later to determine whether that requirement has been adequately fulfilled, because the future state needs to be described in more detail, or the enabling conditions that bring it about, or the relationship between those conditions and the intended outcomes, needs more explanation.

This is typically achieved through acceptance criteria: a set of specific, verifiable properties of the conditions and/or outcomes of a requirement that, when taken together, indicate the requirement is fulfilled.

Acceptance criteria reduce ambiguity by breaking a requirement down into concrete, verifiable aspects. In doing so, they can make the requirement more specific and actionable when doing so is helpful.

They inform the intervention by ruling out those that cannot plausibly satisfy the criteria, and by focusing attention on actions capable of producing the required effects.

It’s especially useful to define acceptance criteria in complicated or complex situations, or when a product or solution needs to be handed over to a customer (within the organization or beyond), because the customer can use them to verify fulfillment without needing to understand the intervention’s technical details.

When defining acceptance criteria, consider the following question:

- What specific, observable indicators would show that the intended outcomes have been adequately achieved?

- What verifiable properties must the enabling conditions have to bring about the intended outcomes?

Sometimes, answering one question or the other is enough to clarify the requirement in a given context.

Once some criteria have been identified, check: Are these criteria taken together sufficient to determine whether the requirement has been fulfilled?

Example: Department Relocation

- Requirement: We need to organize the relocation so that daily operations continue smoothly.

- Acceptance Criteria:

- What specific, observable indicators would show that daily operations continued smoothly during the relocation?

- systems and access remain available

- critical operations meet minimum service levels

- problems that come up are resolved promptly

- What verifiable properties must “organize the relocation” have to bring about the intended outcome?

- Critical operations are identified and protected

- The relocation schedule is aligned with operational needs and communicated with enough time to plan for the relocation

- We know what to do when we hit an unforeseen problem

- Testing proves continuity measures work

- What specific, observable indicators would show that daily operations continued smoothly during the relocation?

In this example, the requirement remains a single, coherent statement of what is needed. The acceptance criteria specify how people will verify that the requirement has been fulfilled in practice.

Not all acceptance criteria need to be made explicit for every requirement. Some standard or “non-functional” criteria may apply across many different requirements, for example:

- product standards

- security or privacy policies

- accessibility standards

- legal or regulatory constraints

Instead of repeating such criteria with each requirement, it is simpler to maintain them as shared standards or policies and reference them where relevant.

When describing acceptance criteria, ensure they are verifiable, relevant, and complete:

- Verifiable: clear pass/fail or measurable thresholds.

- Relevant: it contributes to the requirement’s value in relation to the driver

- Complete: together they cover the full intent of the requirement.

Note: From the perspective of the requirement that is being clarified through acceptance criteria, these acceptance criteria point toward sub-requirements the intervention must fulfill, related to adequately fulfilling the main requirement, typically relating to the enablingg conditions or intended outcomes of that requirement. Acceptance criteria are typically defined as intended outcomes only.

Keep a Record

Record a description of the requirement (for example, in your logbook), and unless it’s obvious, the driver it responds to, along with any acceptance criteria, any context that’s useful to know about, and the key reasons the requirement was chosen. This makes it easier to communicate the requirement and its relevance to others, especially those affected by the intervention and those responsible for carrying it out. It also provides a clear reference point later, when you review the intervention and decide what to improve.