Governance, Operations, Policy

Table of Contents

- How to Distinguish Between Governance and Operations?

- Objectives and Policy

- Steps for Making and Evolving Policies

- Distributing Governance Throughout the Organization

During their daily work, people come across many situations they need to address (organizational drivers) and requirements they need to fulfill. In each case, they need to determine suitable interventions, which may involve operations — doing the work — or governance: creating or evolving decisions about what work will be done (setting objectives) and how (guidelines, strategy, rules, etc.).

Making a clear distinction between operations—the day-to-day work of delivering value to customers — and governance—setting significant objectives and guiding people toward achieving them — ensures that governance matters are addressed in a deliberate, coherent, and incremental manner and, when worthwhile or necessary, through a participatory approach.

Distinguishing between the two is useful because governance requires a different approach and set of activities from those needed to handle day-to-day operations.

Governance the sum of activities involved in setting significant objectives and making and evolving significant decisions (policies) that guide people toward achieving those objectives, for the entire organization or specific people within it.

Operations is doing the work and organizing day-to-day activities within the constraints defined through governance.

A policy is an intervention that is created and evolved through governance; a process, procedure, protocol, plan, strategy, or guideline.

When people think of governance, they often think of corporate governance — the system of rules, practices, and processes for directing and controlling an organization. Traditionally, many of these decisions are seen as the domain of managers and boards of directors, and implemented through hierarchical structures for control and accountability. However, governance as we define and use the term in the context of S3 is broader. Governance occurs at all levels throughout an organization, including within teams and even at the individual level, with many people making and contributing to governance, often without being aware of it. This broader view of governance reveals why it’s valuable for everyone in an organization to understand the concept, how to approach governance, and how it applies to their daily work.

Regardless of how you distribute responsibility for governance throughout the organization, whether it’s more centralized or more distributed, you need clear guidelines and constraints that enable smooth collaboration between teams and individuals and support achieving both long-term and short-term objectives. In S3, we refer to these guidelines and constraints created through governance as policy. Policies guide and constrain people in relation to significant matters such as strategy, priorities, distribution of responsibilities and authority to influence, work processes, and many decisions about products and services.

While decisions with short-term consequences can easily be amended on the spot, making and evolving policies is more consequential because such decisions usually constrain people’s behavior and activities for extended periods of time. To ensure policies become and remain fit for purpose, we recommend a more participatory and deliberate approach to decision-making

As organizations grow and their operations become more complex, developing the capacity for collective sense-making becomes increasingly critical. This involves harnessing diverse perspectives to make and evolve the decisions needed to respond effectively to the various challenges and opportunities they face as they navigate the world’s complexities.

Regular evaluation of outcomes ensures they are adapted, improved, or even discarded as circumstances change and people learn over time.

While doing the work and organizing day-to-day activities (operations) is essential for delivering value to your customers, governance enables operations to be effective and efficient. Consciously and intentionally deciding which objectives to pursue and putting in place policies to achieve those objectives supports everyone throughout the organization in making the best use of their time, energy, and available resources and in working together to fulfill the organization’s purpose most effectively.

How to Distinguish Between Governance and Operations?

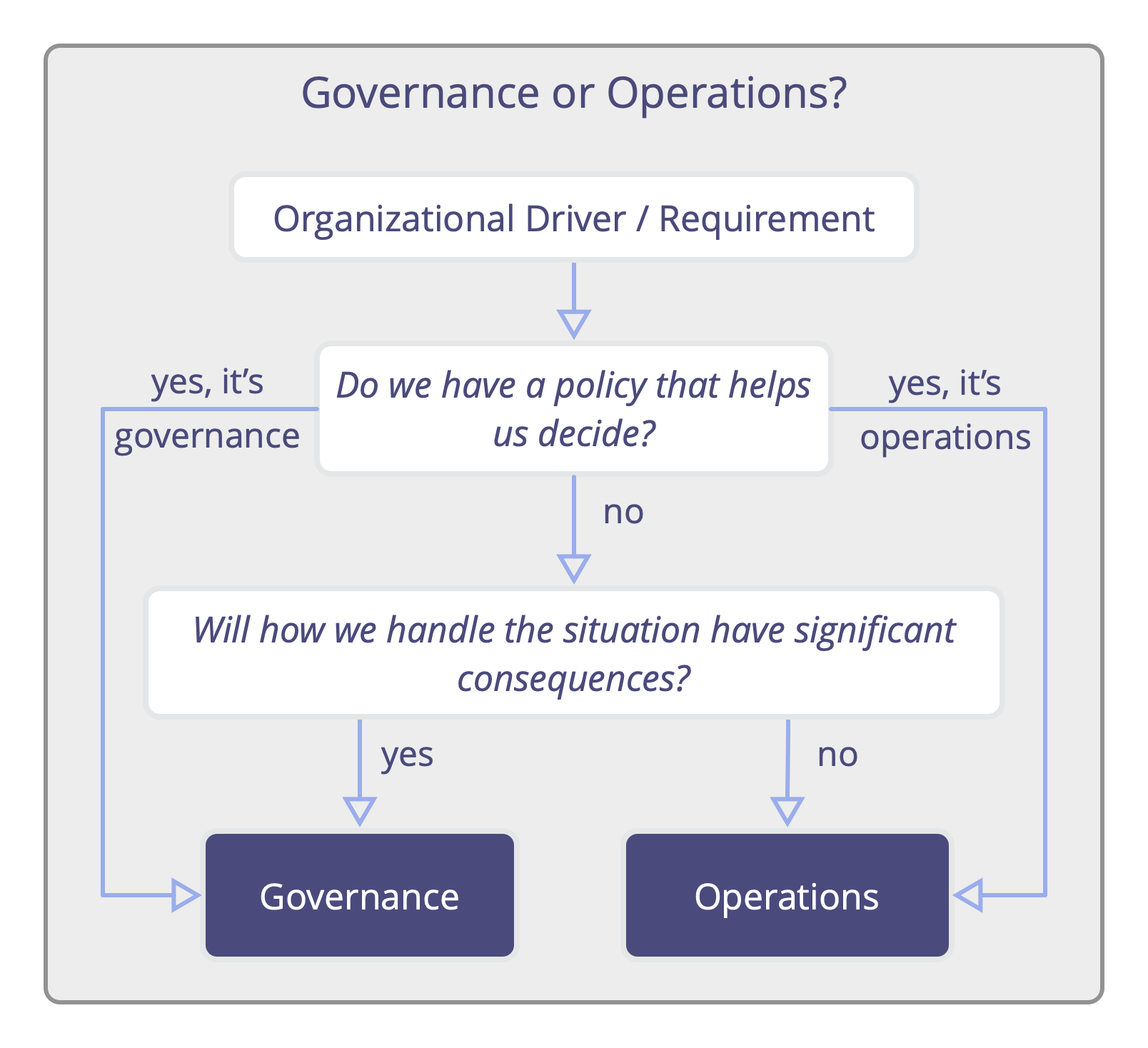

It will usually be clear whether a situation should be handled through governance or operationally. For cases where it’s unclear, first, check if an existing policy helps you decide.

For example, a policy about handling security breaches can inform you whether a new incident can be resolved by implementing existing security protocols (operations) or whether it requires making a new decision with others about how to handle it (governance).

If there is no relevant policy, make a decision whether it is worthwhile to use a formal governance process. Whenever you expect that how you handle the situation may have significant consequences, treat it as governance.

When Is It Worthwhile to Follow a Formal Governance Process?

Worthwhileness is not about whether something counts as governance; rather, it’s about whether it merits going through a formal governance process (however that is defined in your organization, e.g., proposal-forming, policy-making, review scheduling) and deliberately monitoring, reviewing, and if necessary, evolving what has been decided over time.

While all governance decisions govern, not all are processed formally. The practical question is: Is this worth going through a deliberate governance process — documented, reviewed, and evolved — or should we just agree and act?

Indicators that entering a formal governance process is worthwhile:

- The anticipated gain or loss in relation to the situation is significant for the organization.

- The consequences of a specific requirement or intervention you have in mind will be significant.

- The requirement or best approach is unclear.

- The risks are high enough that care, documentation, and review add value.

- The situation you are addressing is ongoing or recurring and would benefit from an agreed, reviewable policy.

- Guidance is needed for others to act effectively.

- The issue affects an entire domain or people in multiple domains.

You can determine significance by looking at factors such as:

- time, effort, and cost required

- opportunity cost or trade-offs

- potential gains or benefits

- exposure to unintended consequences or risks

- duration of the intervention’s impact on the organization

- number of people affected.

If you are in doubt about when to handle situations through a formal governance process, get another opinion. If you find that a certain category of situations is often mishandled, consider creating a policy that helps people act consistently. You can also create policies that guide people in deciding when a specific type of situation should be handled through a formal governance process rather than dealt with informally.

Objectives and Policy

The definition of governance (above) describes two aspects: setting objectives and developing policies that guide people toward achieving those objectives. In the following two sections, we will further clarify what objectives and policies are.

Objectives

An objective is a specific result (or goal) that a person, team, or organization wants to achieve.

Setting objectives applies to both governance and operations. The only distinction is that in governance, the objectives are more significant for the organization.

In organizations, people set and further clarify objectives through the following activities:

- Deciding which situations are relevant and a priority for the organization (or a domain within it) to respond to

- Determining what requirement is suitable to fulfill to address a driver. This clarifies the direction and scope of what will be done.

Alignment and coherence between these decisions are essential: the requirement must be suitable for responding to the driver. Furthermore, since the primary objective of any organization is to fulfill its purpose, all other objectives throughout the organization need to be aligned with that.

Policy

When dealing with matters of governance, requirements are fulfilled through creating and implementing policy.

A policy is an intervention that is created and evolved through governance; a process, procedure, protocol, plan, strategy, or guideline.

Typical examples of Policies include:

- Prioritization of work

- Guidelines and procedures for how people work together

- Distribution of responsibilities and authority to influence by designing domains

- Selecting people to take on responsibility for domains

- Distribution of resources

- Decisions about how to handle dependencies between teams

- Development of organizational, team, or product strategies, etc.

- Consequential decisions about products, services, tools, technology, security, etc.

Each policy is created to fulfill a requirement and, by doing so, to address a driver adequately.

It’s useful to record policies to support their effective review and evolution. When describing policies, at the very least, include the following information:

- Purpose (driver and requirement)

- Intended Outcome(s)

- Policy description (including rationale)

- Who’s responsible for what

- Review date(s) Metrics and Monitoring

Creating Policies

Policies can be created by individuals or groups, depending on the context. Since creating policies is a governance activity often situated within a complex domain, involving relevant stakeholders in co-creation is valuable.

Depending on the context, people might create policies:

- in regular, dedicated governance meetings

- on the fly during the workday, when useful or urgent

- in a one-off meeting to deal with a specific topic

- in other types of meetings, such as product meetings, planning meetings, or retrospectives, etc.

Iterative and Incremental Development of Policies

Developing policies iteratively and incrementally, based on continuous learning, enhances the organization’s ability to remain effective, relevant, and responsive to unforeseen challenges and opportunities.

When aiming for ‘perfect’ policies, people often invest significant time and effort, and once established, the need to change them can trigger resistance. Instead, focus on designing safe-to-fail experiments that you regularly evaluate and evolve based on learning.

This ongoing evolution of policies supports the organization’s ability to adapt, reducing the risk of stagnation and enabling continuous improvement. To ensure this, schedule regular evaluations of policies and resolve any objections promptly when they arise.

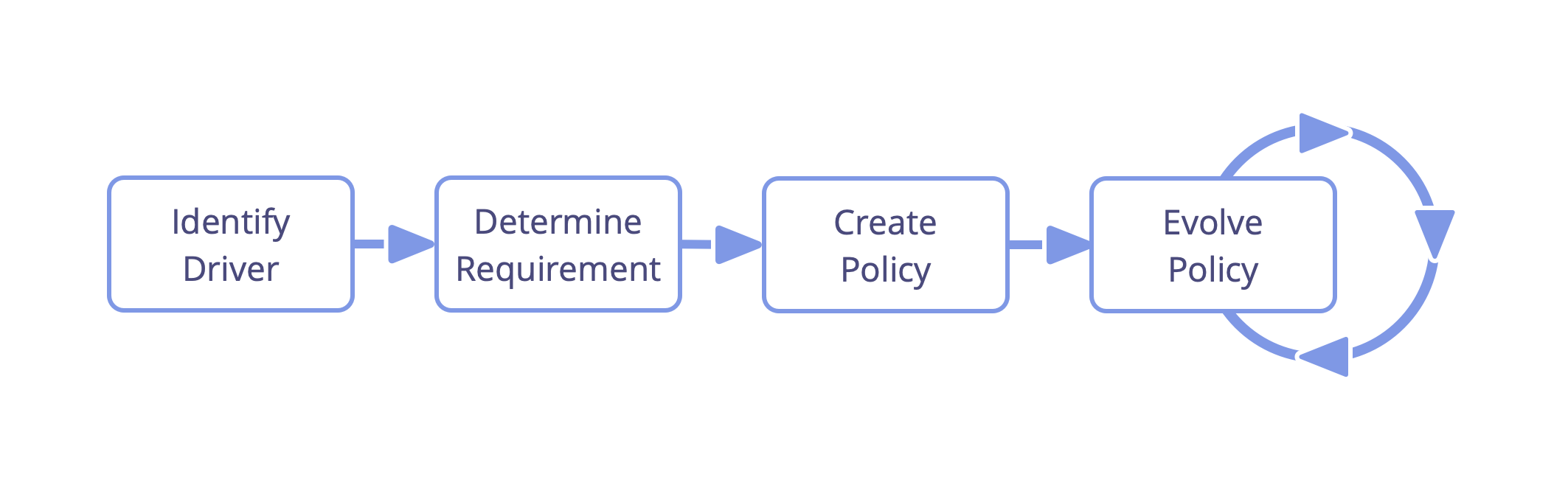

Steps for Making and Evolving Policies

Whether or not you use S3 patterns to address matters of governance in your organization, there are a number of typical stages people who are successful in matters of governance follow to make and evolve effective policies:

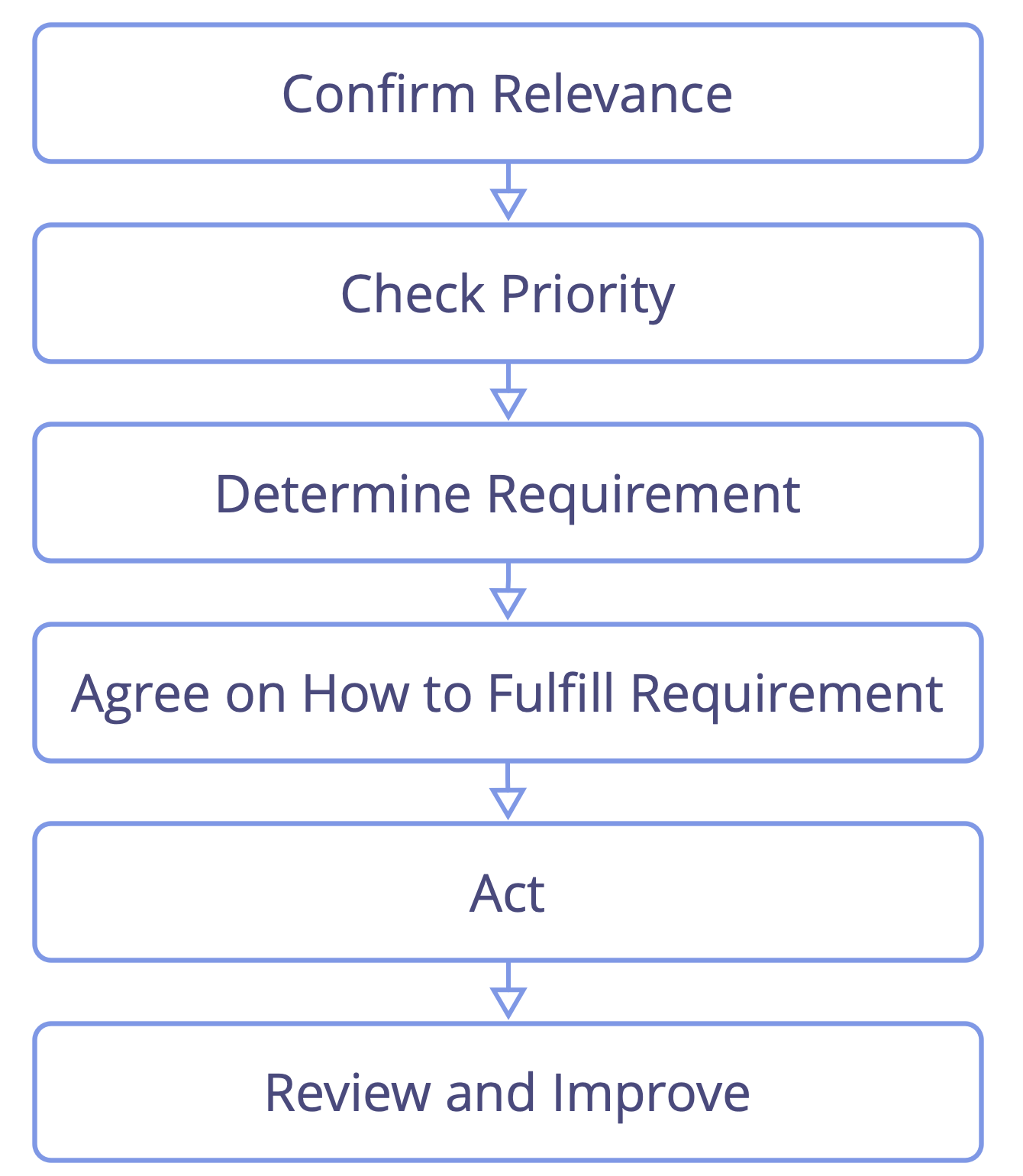

- Confirm the Relevance of the situation to ensure the effort is not wasted

- Determine Priority to ensure drivers are addressed in order of their importance.

- Determine Requirement to decide on the scope and direction of the efforts

- Determine intervention (in this case, a policy)

- Create a Proposal for a policy that describes what will be done, which constraints will be put in place, etc.

- Resolve any Objections that have been identified to ensure the policy is adequate for fulfilling the requirement and responding to the driver

- Evaluate and Policy and Evolve it as necessary to ensure it remains fit for purpose.

You’ll find that similar steps apply to both operations and governance. For more information, see Respond to Organizational Drivers

Check your current governance processes to see if all those steps are included, and in general, take a conscious and intentional approach to how you handle governance of your domain and the whole organization.

Distributing Governance Throughout the Organization

Every organization requires ongoing governance, both for the whole system, and each domain within it.

Due to their complex nature, running organizations effectively requires distributing responsibilities, including responsibility for governance, in a way that enables everyone throughout the organization to work as productively as possible to deliver value related to the domains they are responsible for, while maintaining coherence and effectiveness across the organization.

Each domain within an organization needs to be designed and evolved in a way that those responsible can fulfill its purpose effectively, while ensuring coherence with the organization as a whole. That process includes clarifying who has responsibility and authority for making which governance decisions relating to the domain, who else should be involved, and to what extent.

Designing a domain is itself an act of governance that precedes the existence of the domain and establishes who will be responsible for its governance. Once a domain exists, the delegator may play a more or less active role in its governance. However, they will always retain overall responsibility for evolving the design of the domain, even though they may involve others, especially the delegatees.

For an organization to be effective, domains need to be designed and evolved with consideration for the wider system of domains within which they are embedded. Furthermore, the entire system of domains needs to be continuously evolved to ensure its ongoing effectiveness in fulfilling the organization’s overall purpose. In some contexts, delivery of value is best served by giving delegatees authority to handle aspects of governance relating to their domain autonomously. In other contexts, effective governance requires collaboration across multiple domains, either because it is necessary or beneficial. To determine the right balance of autonomy and dependencies, organizations may need to periodically redesign the distribution of governance across multiple domains, or even across the whole organization.

Who governs a domain?

Each domain in an organization has a governing body: one or more people who are responsible for making governance decisions relating to the fulfillment of the purpose of that domain. Typically, the governing body consists of the delegator (those who created the domain) and often the delegatee(s) who took on responsibility for attending to it.

Depending on how a domain is designed, governance decisions may be made primarily by the delegator, by the delegatee(s), or shared between them. At times, representatives from other domains, outside experts, or other stakeholders may also be involved in the governing body, at least for working on certain topics. Some members of the governing body may be involved in all governance decisions relating to a domain, while others may only be brought in for certain topics or aspects.

In some cases, delegatees are not only responsible for governance decisions within the constraints of the domain, but may also be invited to collaborate with the delegator in developing or evolving the domain’s design. Involving delegatees early in domain design and maintaining their involvement over time is often beneficial. The delegator, however, retains ultimate authority for defining the domain’s purpose and its overall design. (see Clarify and Develop Domains)

The distribution of responsibilities related to governance should be documented so that everyone shares the same understanding. If it’s unclear who is responsible for which decisions, those decisions risk not being made properly or being made inconsistently. “Who” may refer to a specific person, or to a function or role (e.g., a representative of a domain). This information can be captured in a domain description (especially in the sections: Key Responsibilities, Deliverables, Dependencies, External Constraints, and Delegator Responsibilities).

When role keepers or teams have formal responsibility for making and evolving certain governance decisions, they are considered to be self-governing within their domain. By contrast, when they have no formal authority, they simply carry out operational work assigned by their delegator.

In all cases, people in organizations are semi-autonomous. Their freedom to decide and act is limited, not only by the boundaries of their domain, but also by constraints set by the wider organization and the external environment. In many cases, people may be required to pass on information about a situation requiring a decision to others with authority to make it, even if the situation and any decision that follows might affect them (see Navigate via Tension). In organizations that apply the principle of consent, autonomy is further constrained by any objections raised.

Considerations for Effectively Distributing Governance

To determine how much authority for governance to delegate to a role keeper or team, consider the following aspects:

- Distribution of governance between delegator and delegatee(s): What can delegatees handle independently, which matters should the delegator retain responsibility for or participate in, and which require outside expertise?

- Addressing dependencies between domains: For which decisions should people from outside the domain be involved because they are affected, or because collaboration on governance is worthwhile?

Example: A team responsible for the marketing domain has the authority to decide which partnerships and collaborations to pursue to extend market reach. The team manages its own budget, but must clear anything that costs more than 5.000 with the delegator. Any decisions regarding campaign schedules must be made in collaboration with the Product team.

Distribution of Governance Between Delegators and Delegatees

Role keepers and teams often have responsibility for certain governance decisions, such as planning work and developing work processes. However, they may also take on responsibility for more consequential matters such as developing their own strategy, managing their own profit and loss, or even recruiting new team members.

When delegatees get more authority to decide how to address challenges and opportunities in their domain, they tend to take greater ownership over both decisions and outcomes. It also allows them to respond more quickly and with greater scope to create and innovate according to their own abilities and interests, as opposed to waiting on a decision-making hierarchy that can cause unnecessary delays and separate decision-making from the knowledge and experience of those closest to the work and its relevant context.

Which governance matters to delegate depends on both the delegatees’ level of competence and experience in the subject matter, as well as their level of experience with governance decision-making. Where certain domain expertise is lacking, a delegator might remain involved in making certain decisions or bring in others with relevant experience and expertise, until delegatees develop the capacity to make such decisions autonomously.

Making and evolving governance decisions requires a certain skillset, especially in cases where a collaborative approach is required. Understanding the governance process, as well as the various related practices, is essential for delegatees to effectively take on responsibility for governance. A delegator can also bring in a coach or facilitator to help the delegatees develop their capacity for governance decision-making, which will, over time, increase their capacity to effectively handle governance by themselves.

Addressing Dependencies Between Domains

Determining the right balance of autonomy and dependency for each domain requires ongoing evaluation of its design in light of how it contributes to delivering value within the overall system of domains. This balance is specific to each domain and needs to be regularly assessed and evolved — whether by removing unnecessary or unhelpful dependencies to speed up decision-making, or addressing unavoidable (or helpful) dependencies by bringing in outside influence for certain governance decisions.

When distributing governance responsibilities, it’s important to consider which dependencies you create or resolve. Involving others in decision-making saves time, energy, and resources, but it can also introduce cost, delay, or risk. If dependencies are avoidable, it’s worth weighing the benefits against the drawbacks before involving others, or designing the domain so that delegatees have the authority to decide for themselves.

When distributing governance between domains, consider the operational dependencies between domains, the degree of significance of certain decisions, and who will be affected. As a general rule of thumb, governance decisions that impact other domains (e.g., due to dependencies) should be made with consideration for those other domains to ensure those decisions don’t impede their effectiveness.

When individuals or teams lack the authority to make certain decisions for themselves, they should pass that information on to those who do.

If trade-offs involve more than two domains, resolving them requires considering the wider network of governance dependencies as well. Some domains form closely related subsystems that depend on ongoing collaboration, while others can operate with minimal interaction. The right balance of autonomy and dependency requires evaluating each domain’s role in delivering value within the broader system.

Autonomy and coherence may appear contradictory, but in practice, they are complementary. Both need to be balanced and adjusted continually to maintain effectiveness across the organization. (See also: Enable Autonomy and Collaborate on Dependencies).