A Practical Guide for Evolving Agile and Resilient Organizations with Sociocracy 3.0

What is Sociocracy 3.0?

Sociocracy 3.0 – a.k.a. “S3” – is social technology for evolving agile and resilient organizations at any size, from small start-ups to large international networks and multi-agency collaboration.

Inside this practical guide you’ll discover a comprehensive collection of tried and tested concepts, principles and practices for improving performance, engagement and wellbeing in organizations.

Since its launch in 2015, S3 patterns have been helping people across a diverse range of organizational contexts to get the best out of collaboration: from start-ups to small and medium businesses, large international organizations, investor-funded and nonprofit organizations, families and communities.

Using S3 can help you to achieve your objectives and successfully navigate complexity. You can make changes one step at a time, without the need for sudden radical reorganization or planning a long-term change initiative:

- Simply start with identifying your areas of greatest need and select one or more practices or guidelines that help.

- Proceed at your own pace, and develop your skills and competences as you go.

Regardless of your position in the organization, you’ll find many proven ideas that are relevant and helpful for you.

Sociocracy 3.0 is free, and licensed under a Creative Commons Free Culture License.

How does Sociocracy 3.0 help?

S3 is a transformational technology for both individuals and the whole organization that will help you figure out how to meet your organization’s biggest challenges, take advantage of the opportunities you face and resolve the most persistent problems.

Sociocracy 3.0 is designed to be flexible and supports experimentation and learning. You can take whatever you need, adapt things to suit your context and enrich your existing approach.

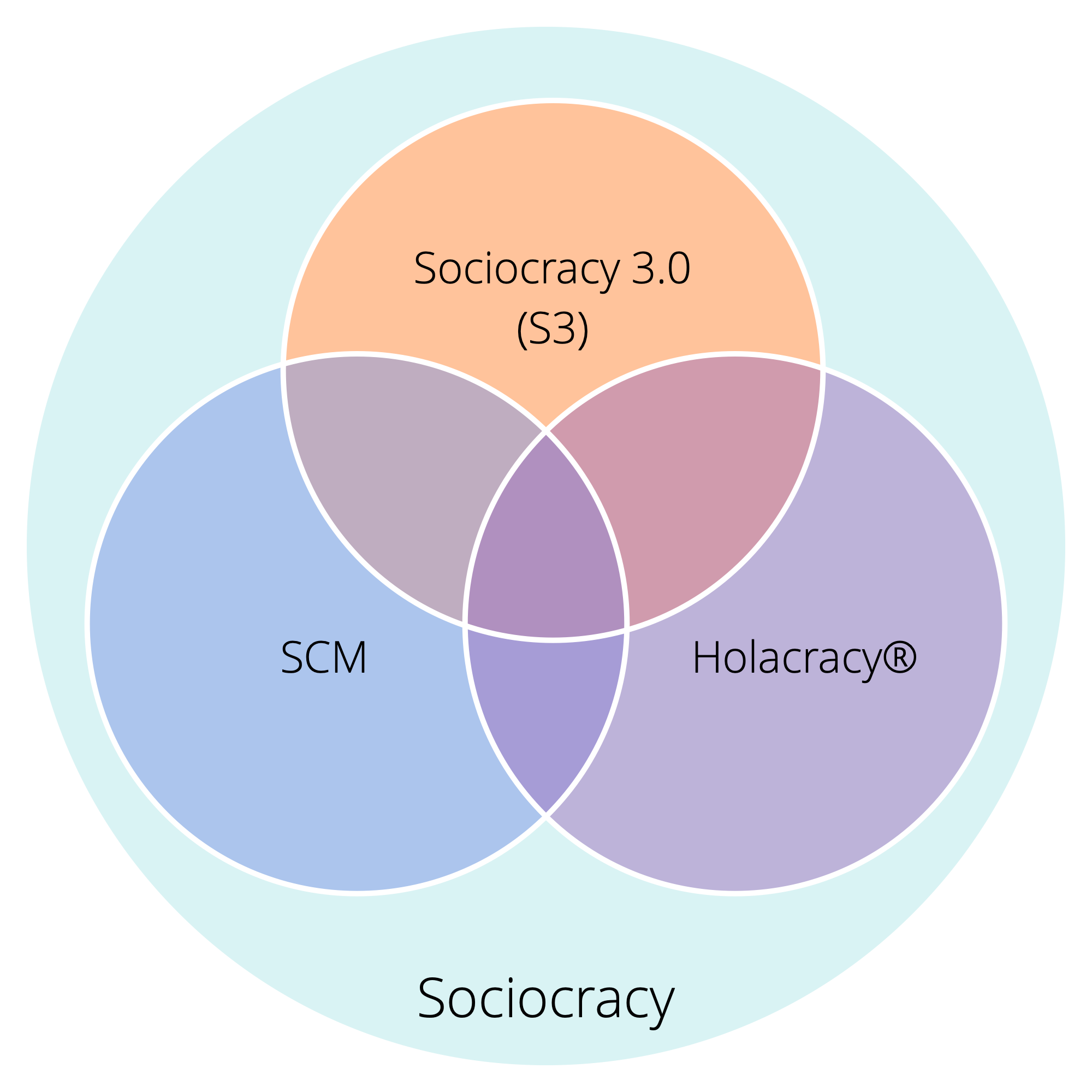

S3 integrates core concepts and practices found in agile methodologies, lean management, Kanban (and KMM), Design Thinking, Teal Organizations and the family of sociocracy-based governance methods (SCM/Dynamic Governance, Holacracy® etc.). It’s complementary and compatible with any agile or lean framework, including but not limited to Scrum and its various scaling frameworks.

A Pattern-Based Approach to Organizational Change

S3 offers a pattern-based approach to organizational change.

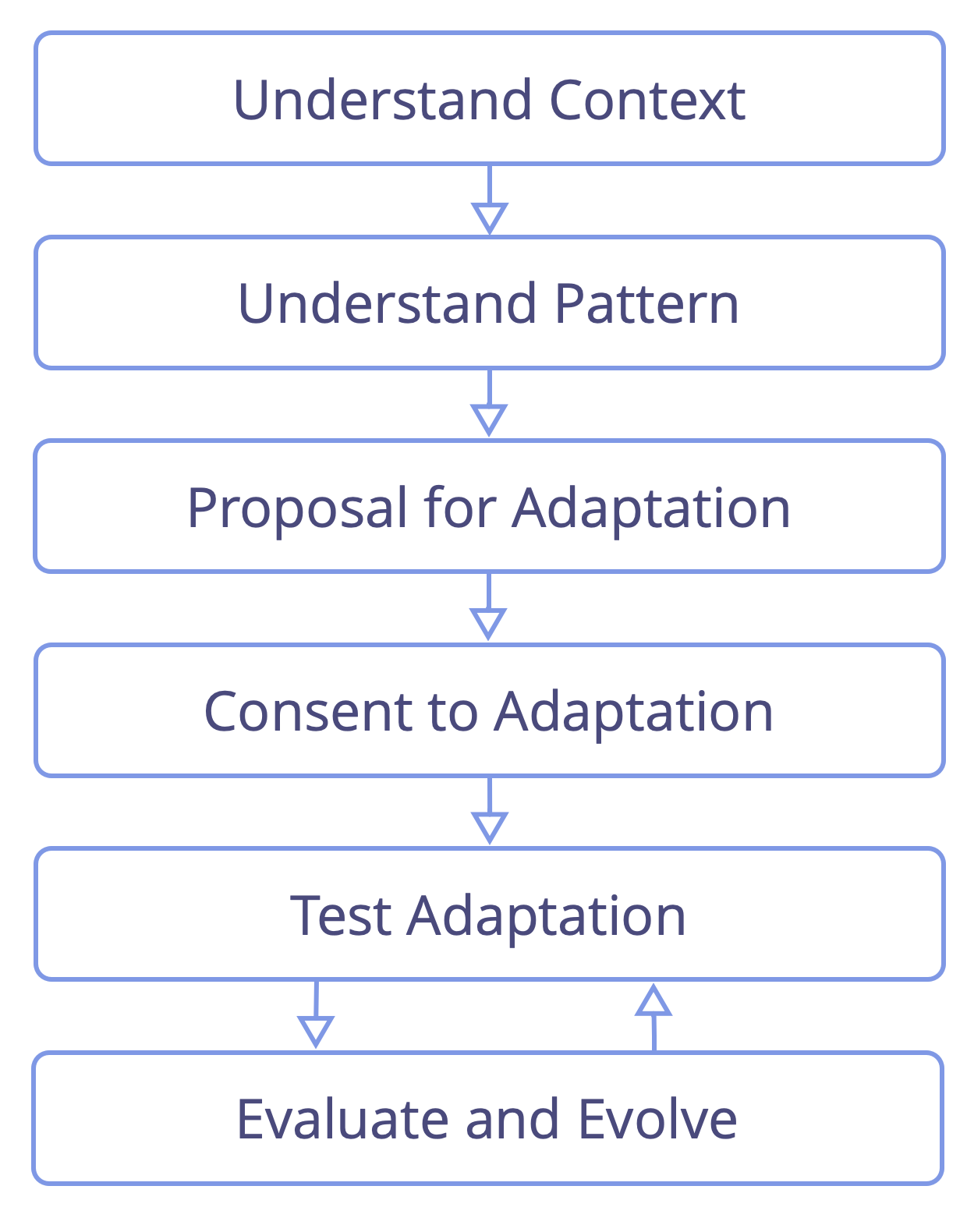

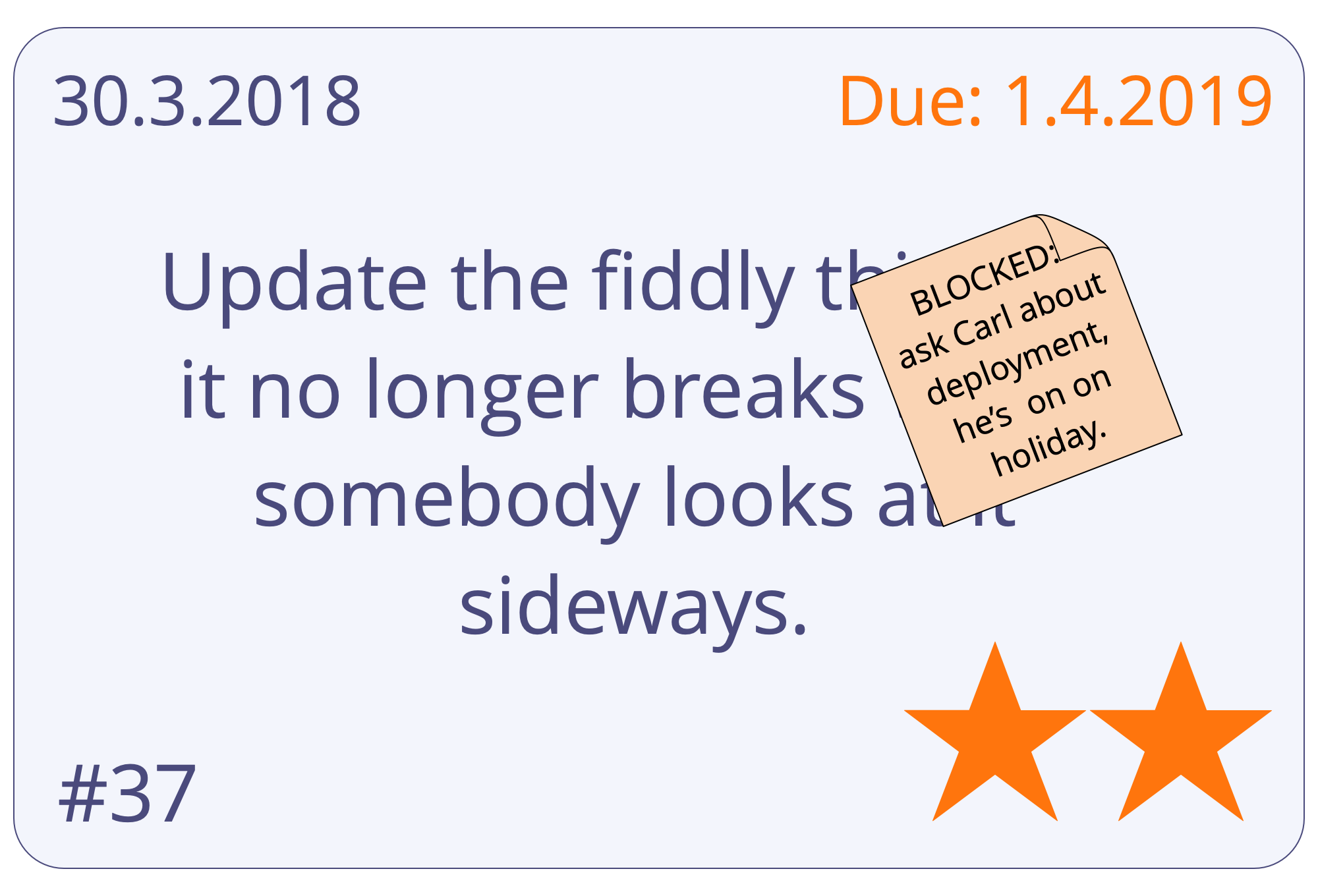

A pattern is a process, practice or guideline that serves as a template for successfully responding to a specific kind of challenge or opportunity. S3 patterns are discovered through observing people working together in organizations to solve problems and respond to opportunities they face. When you find that your habitual ways of doing things fail to bring about the outcomes you expected or hope for, you can look to S3 for patterns that might help.

Patterns are modular and adaptable, can be used independently, and are mutually reinforcing, complementing one another when used in combination. S3 patterns can be evolved and adapted to address your specific needs.

In this guide, the patterns are grouped by topic into eleven categories to help you more easily identify those that are useful to you:

- Sense-Making and Decision-Making

- Evolving Organizations

- Peer Development

- Enablers Of Co-Creation

- Building Organizations

- Bringing In S3

- Defining Agreements

- Meeting Formats

- Meeting Practices

- Organizing Work

- Organizational Structure

By providing a menu of patterns to choose from according to need, S3 encourages an organic, iterative approach to change without a huge upfront investment. It meets people where they are and helps them move forward pulling in patterns at their own pace and according to their unique context.

What’s in this guide?

Inside this practical guide book you’ll discover:

- Useful concepts that will help you make more sense of your organization and communicate effectively about where change is needed.

- An organic, iterative approach to change that meets people where they are and helps them move forward at their own pace and according to their unique context and needs.

- Seven core principles of agile and sociocratic collaboration

- A coherent collection of 70+ practices and guidelines to help you navigate complexity, and improve collaboration:

- Simple, facilitated formats that support teams in drawing on the collective intelligence of the group and incrementally processing available information into continuous improvement of work processes, products, services and skills.

- Group-practices to help organizations make the best use of talent they already have, through people supporting each other in building skills, accountability and engagement.

- Simple tools for clarifying who does what, freeing people up to decide and act for themselves as much as possible, within clearly defined constraints that enable experimentation and development.

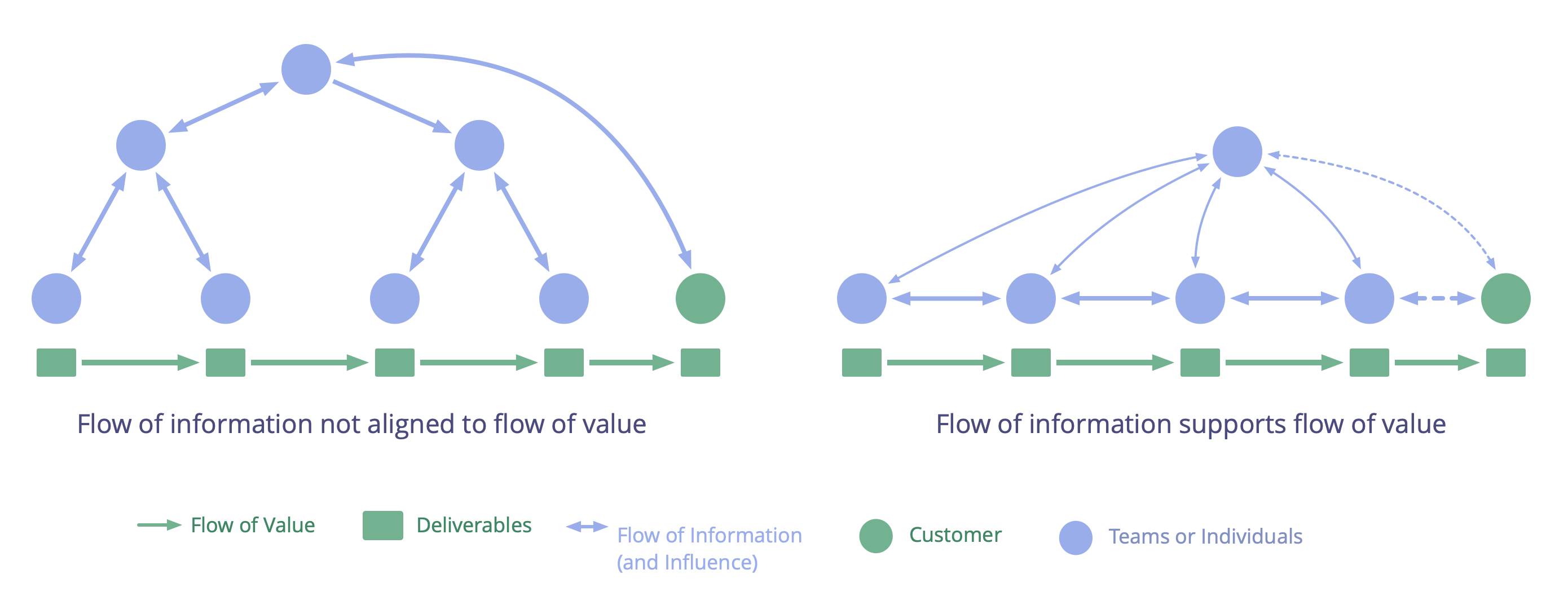

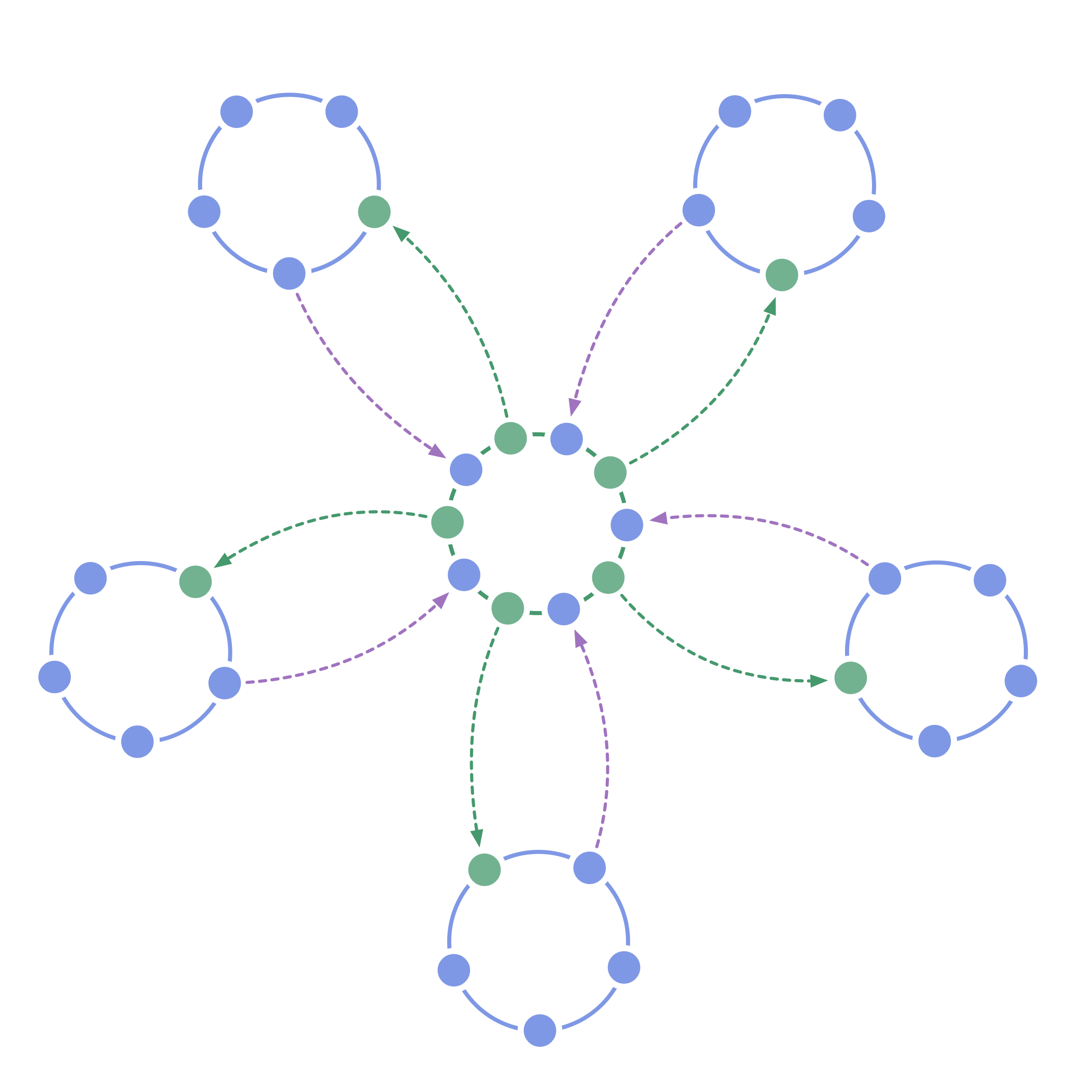

- Patterns for growing organizational structure beyond hierarchies into flexible, decentralized networks where the flow of information and influence directly supports the creation of value.

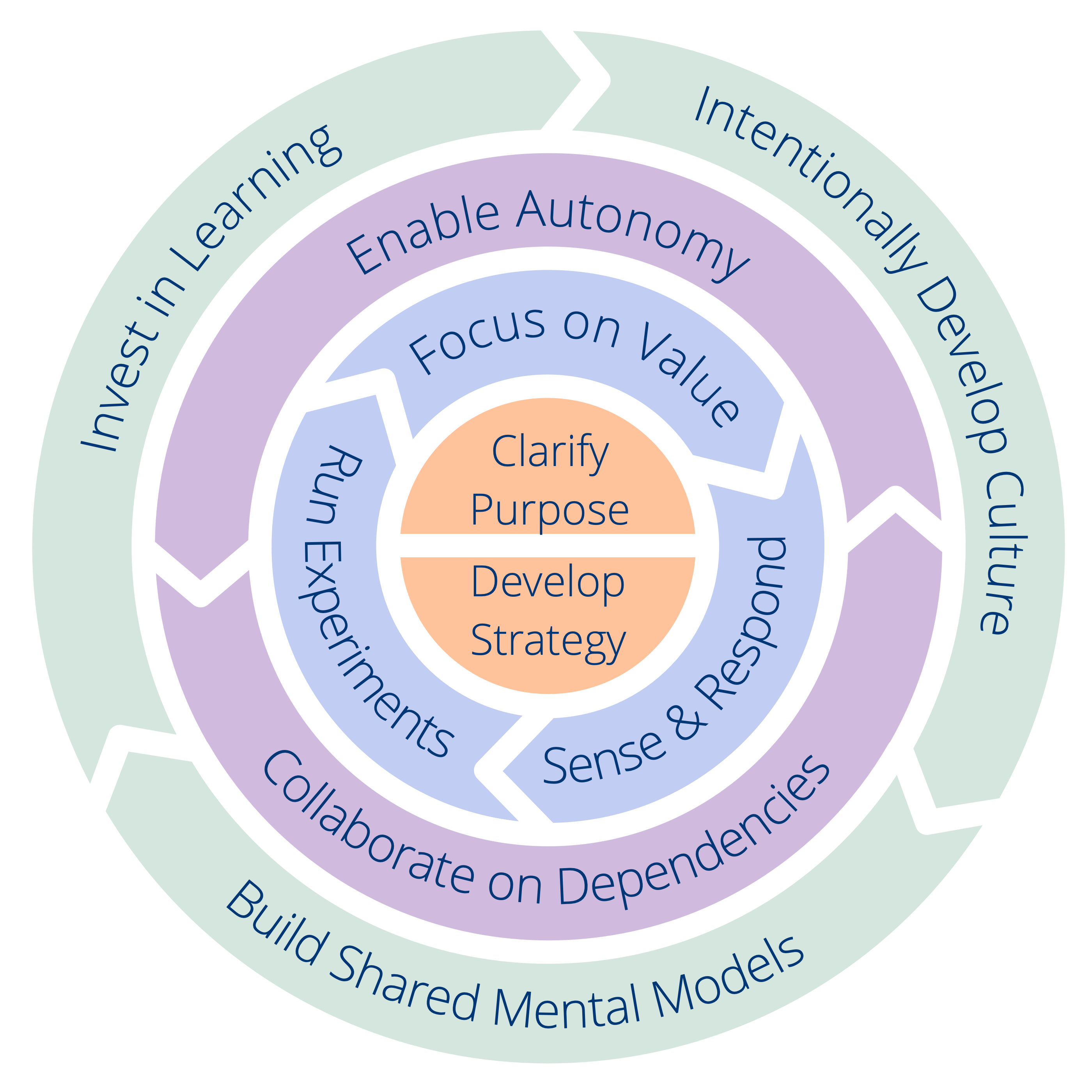

- The Common Sense Framework, a tool for making sense of teams and organizations and figuring out how to get started with S3.

- A glossary with explanations for all the terms you might be unfamiliar with.

This practical guide to Sociocracy 3.0 is written and published by the three co-developers of Sociocracy 3.0.

True to the mindset behind S3, this book will always be a work in progress that grows and changes as we learn from people who are experimenting with S3 in organizations around the world. Since we started out in 2015, we have released several updates per year and we’ll continue to do so in the years to come.

Even though several sections in this book are brief and may still be rough around the edges, the content and explanations have been sufficient for many people to get started with S3 and achieve positive change in their organizations. We hope you’ll find it useful too.

Influences and History of Sociocracy 3.0

The literal meaning of the term sociocracy is “rule of the companions”: socio — from Latin socius — means “companion”, or “friend”, and the suffix -cracy — from Ancient Greek κράτος (krátos) — means “power”, or “rule”.

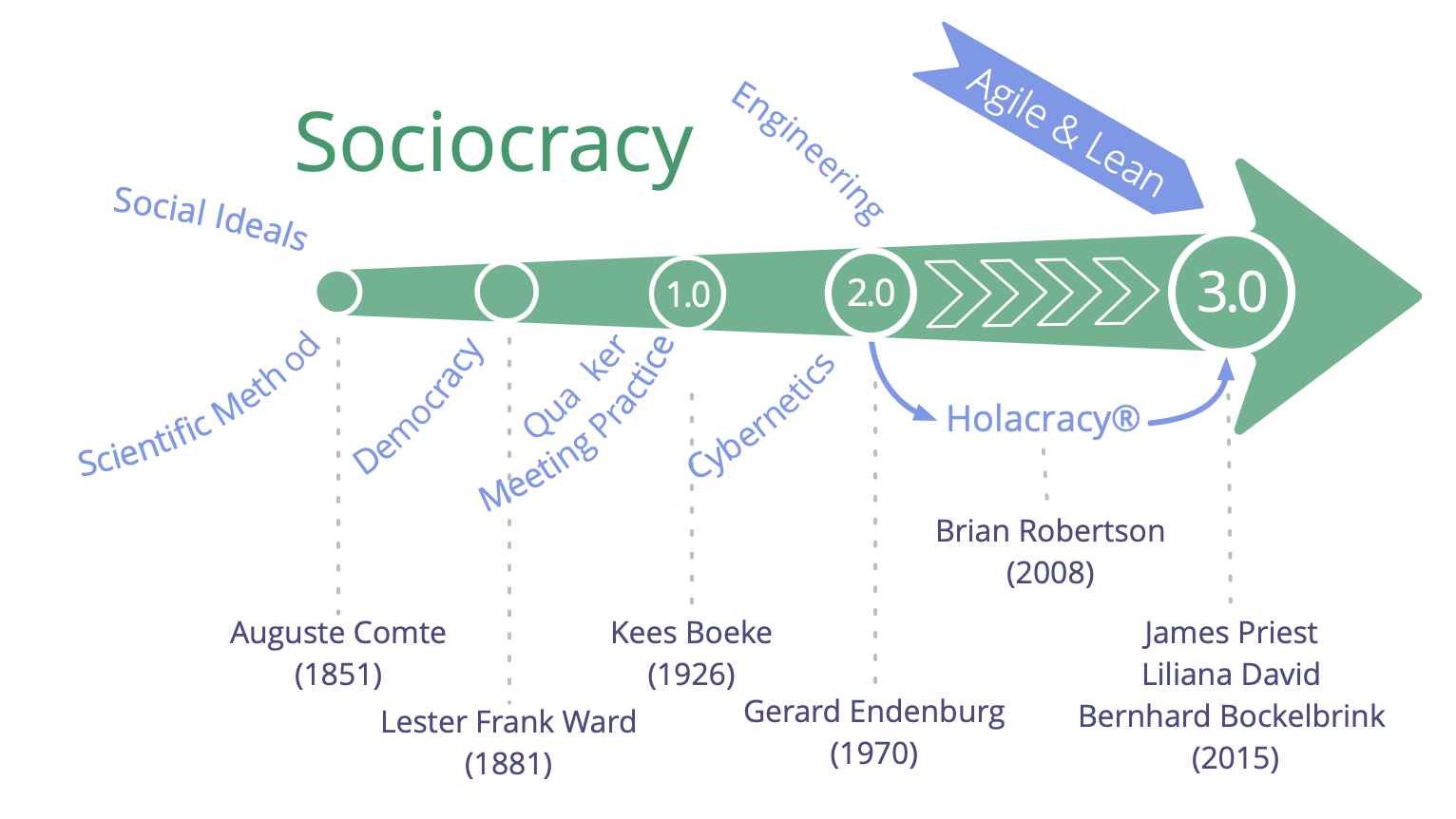

The word sociocracy can be traced back to 1851, when Auguste Comte suggested applying a scientific approach to society: states would be governed by a body of scientists who are experts on society (which he termed “sociologists”). In his opinion, this future, although not yet achievable, would be inevitable.

A few decades later, Lester Frank Ward, used the word ‘sociocracy’ to describe the rule of people with relations with each other. Instead of having sociologists at the center, he wanted to give more authority and responsibility to the individual, he imagined sociologists in a role as researchers and consultants.

In 1926, the Dutch reformist educator and Quaker Kees Boeke, established a residential school based on the principle of consent. Staff and students were treated as equal participants in the governance of the school, all decisions needed to be acceptable to everyone. He built this version of sociocracy on Quaker principles and practices, and described sociocracy as an evolution of democracy in his 1945 essay “Democracy as it might be”.

Gerard Endenburg, also a Quaker and a student in Boeke’s school, wanted to apply sociocracy in his family’s business, Endenburg Elektrotechniek. He created and evolved the Sociocratic Circle Organisation Method (SCM) (later becoming the “Sociocratic Method”), integrating Boeke’s form of sociocracy with engineering and cybernetics. In 1978 Endenburg founded the Sociocratisch Centrum in Utrecht (which is now the Sociocratic Center in Rotterdam) as a means to promote sociocracy in and beyond the Netherlands. Since 1994 organizations in the Netherlands using SCM have been exempt from the legal requirement to have a worker’s council.

During the late 1990s and early 2000s, several non-Dutch speaking people came across sociocracy, but it wasn’t until 2007 when Sharon Villines and John Buck launched their book, “We the People”, that sociocracy became widely accessible to the English speaking world, and from there has begun to migrate into several other languages.

Sociocracy has proven to be effective for many organizations and communities around the world, but it has yet to become viral.

In 2014 James Priest and Bernhard Bockelbrink came together to co-create a body of Creative Commons licensed learning resources, synthesizing ideas from Sociocracy, Agile and Lean. They discovered that organizations of all sizes need a flexible menu of practices and structures — appropriate for their specific context — that enable the evolution of a more sociocratic and agile approach to achieve greater effectiveness, coherence, fulfillment and wellbeing. The first version of Sociocracy 3.0. was launched in March 2015.

Liliana David joined the team soon after. Together they regularly collaborate to make S3 available and applicable to as many organizations as possible, and provide resources under a Creative Commons Free Culture License for people who want to learn, apply and tell others about Sociocracy 3.0.

The Sociocracy 3.0 Movement

As interest in Sociocracy 3.0 grows there is a fast growing community of people from a variety of backgrounds — pioneering consultants, coaches, learning facilitators, and people applying S3 into their various contexts — who share appreciation for the transformational potential of Sociocracy 3.0 to help organizations and their members thrive. Many kindly dedicate some of their time to experimenting with and sharing about S3, and who collaborate to learn from one another and document experiences to inform the ongoing development and evolution of the S3 and its various applications.

Why “3.0”?

Sociocracy as a form of governance has been referred to since 1851. Subsequently it has been developed and adapted by many different people and organizations, including Gerard Endenburg, The Sociocracy Group (TSG) and Brian Robertson (HolacracyOne).

Yet, outside the Netherlands sociocracy has until recently remained largely unknown.

We love sociocracy because we see organizations and their members thrive when they use elements of it to enrich or transform what they currently do.

We also love agile, lean, Kanban, the Core Protocols, Non-Violent Communication, and many other ideas too. We believe that the world will be a better place as more organizations learn to pull from this cornucopia of awesome practices that are emerging into the world today, and learn to synthesize them with what they already know.

Therefore we decided to devote some of our time to develop and evolve Sociocracy, integrating it with many of these other potent ideas, to make it available and applicable to as many organizations as possible.

To this end, we recognize the value of a strong identity, a radically different way of distribution, and of adapting the Sociocratic Circle Organization Method to improve its applicability.

The Name

The name “Sociocracy 3.0” demonstrates both respect to the lineage and a significant step forward.

It also helps avoid the perception of us misrepresenting the Sociocratic Circle Organization Method (SCM) as promoted by The Sociocracy Group (TSG), The Sociocracy Consulting Group, Sociocracy For All (SoFA), Governance Alive, and many others.

The New Model of Distribution

Sociocracy 3.0 employs a non-centralized model for distribution. This is a paradigm shift in the way sociocracy is brought to people and organizations, and one that many people can relate to.

We support “viral” distribution through two key strategies:

- Sociocracy 3.0 is open: We want to encourage growth of a vibrant ecosystem of applications and flavors of sociocracy, where people share and discuss their insights and the adaptations they are making for their specific context. To this end Sociocracy 3.0 puts emphasis on communicating the underlying principles and explicitly invites the creativity of everyone to remix, extend and adapt things to suit their needs.

- Sociocracy 3.0 is free: To eliminate the barrier of entry for people and organizations we provide free resources under a Creative Commons Free Culture License to learn, practice and teach Sociocracy 3.0. Everyone can use our resources without our explicit permission, even in a commercial context, or as a basis for building their own resources, as long as they share their new resources under the same license. We expect and support other organizations, consultants, coaches, learning facilitators and trainers to follow our example and release their resources too.

The Evolution of the Sociocratic Circle Organization Method

Maybe we need to make this explicit: Sociocracy 3.0 is not targeted specifically at the existing community of people exploring or using the Sociocratic Circle Organization Method (SCM). SCM is already well developed and of those people who use it, many appear to be mostly happy with it.

Yet from our direct experience, for most organizations, the methodology is either insufficient or inappropriate for addressing many of their needs. With Sociocracy 3.0 we actively work on addressing these limitations and inadequacies by developing new patterns and eliminating what stands in the way.

Reducing Risk and Resistance

Sociocracy 3.0 meets organizations where they are and takes them on a journey of continuous improvement. There’s no radical change or reorganization. Sociocracy 3.0 provides a collection of independent and principle-based patterns that an organization can pull in one by one to become more effective. All patterns relate to a set of core principles, so they can easily be adapted to context.

Shifting Focus from Vision to Need

Sociocracy 3.0 moves primary focus away from attempting to realize a vision, toward understanding the current reality and determining what is required to achieve an organization’s objectives. Organizations which are already need-driven, value driven or customer-centric, find this immediately accessible.

Condensed to the Essentials

When looking at the norms, the Sociocratic Circle Organization Method may look big and scary. By focusing on the essentials only, Sociocracy 3.0 offers a more lightweight starting point to adapt and build on as necessary.

This doesn’t mean to say it’s all easy: choosing to pull in Sociocracy 3.0’s patterns requires an investment in learning and unlearning. This is why it’s important to only pull in what you need, because there’s no point to changing things if what you are doing is already good enough.

Integration With Agile and Lean Thinking

The Sociocratic Circle Organization Method is an “empty” method when it comes to operations and creating a culture of close collaboration. Many organizations already implement or show preference for lean and agile thinking for operations and collaboration. We believe this is a great idea, so Sociocracy 3.0 is designed for easy adoption into lean and agile organizations.

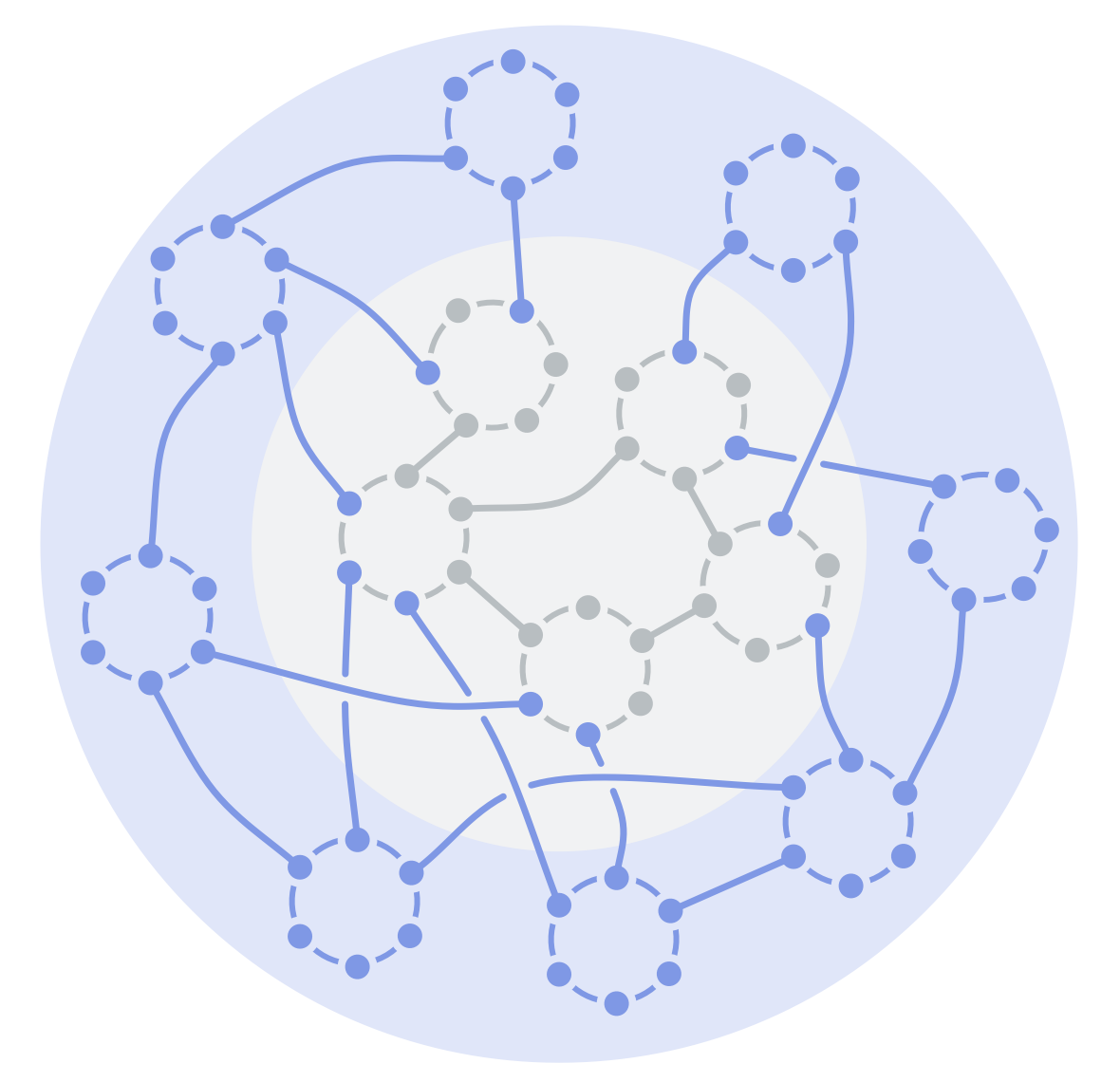

A New Way to Evolve Organizational Structure

The organizational structure according to the Sociocratic Circle Organization Method is modeled on a hierarchy of domains. We see an increasing emergence of collaborative multi-stakeholder environments and the need for a wider variety of patterns for organizational structure. Evolution of organizational structure happens naturally when the flow of information and influence in an organization is incrementally aligned to the flow of value. Sociocracy 3.0 provides a variety of structural patterns that can be combined to evolve structure as required and in a flexible way.

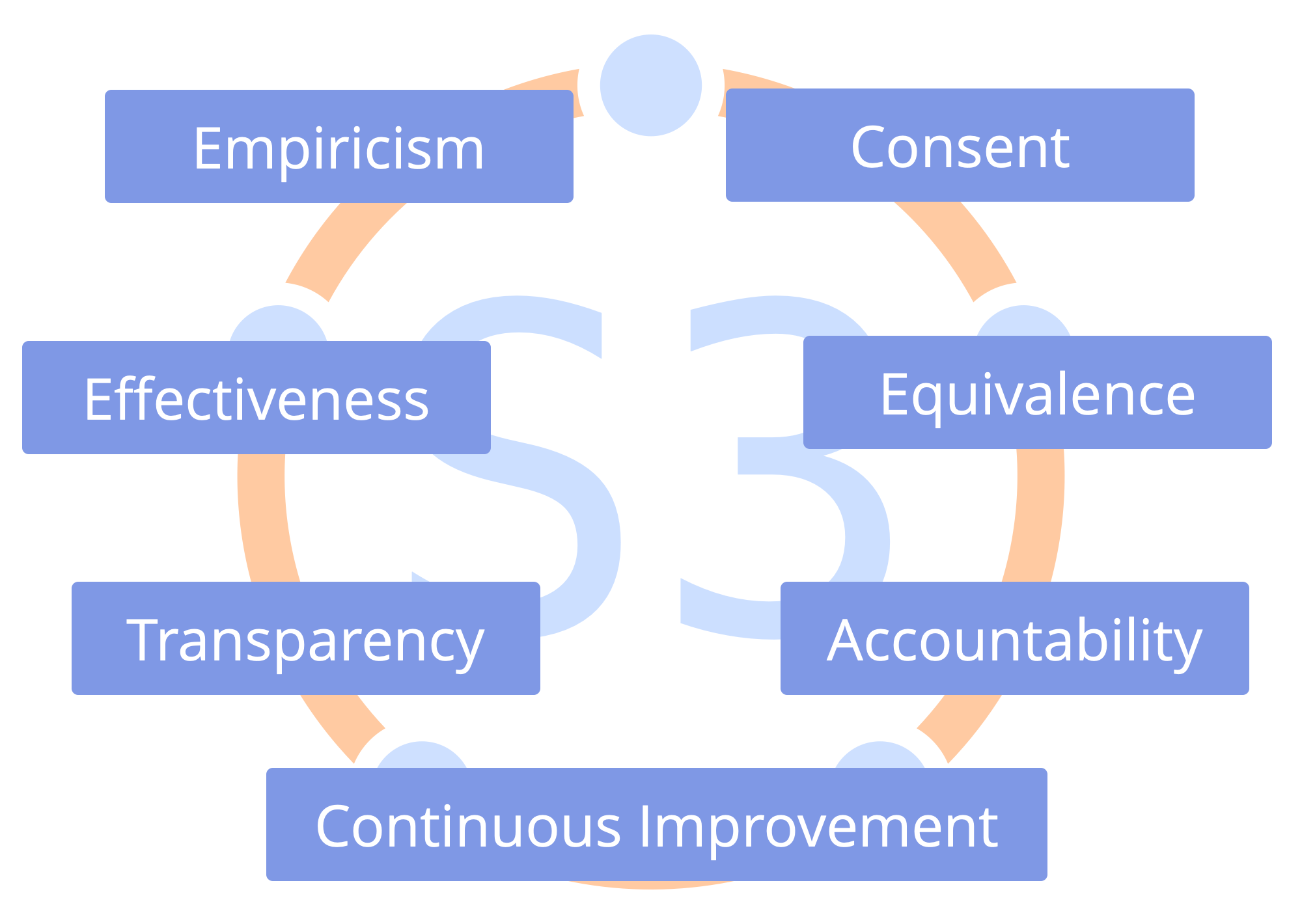

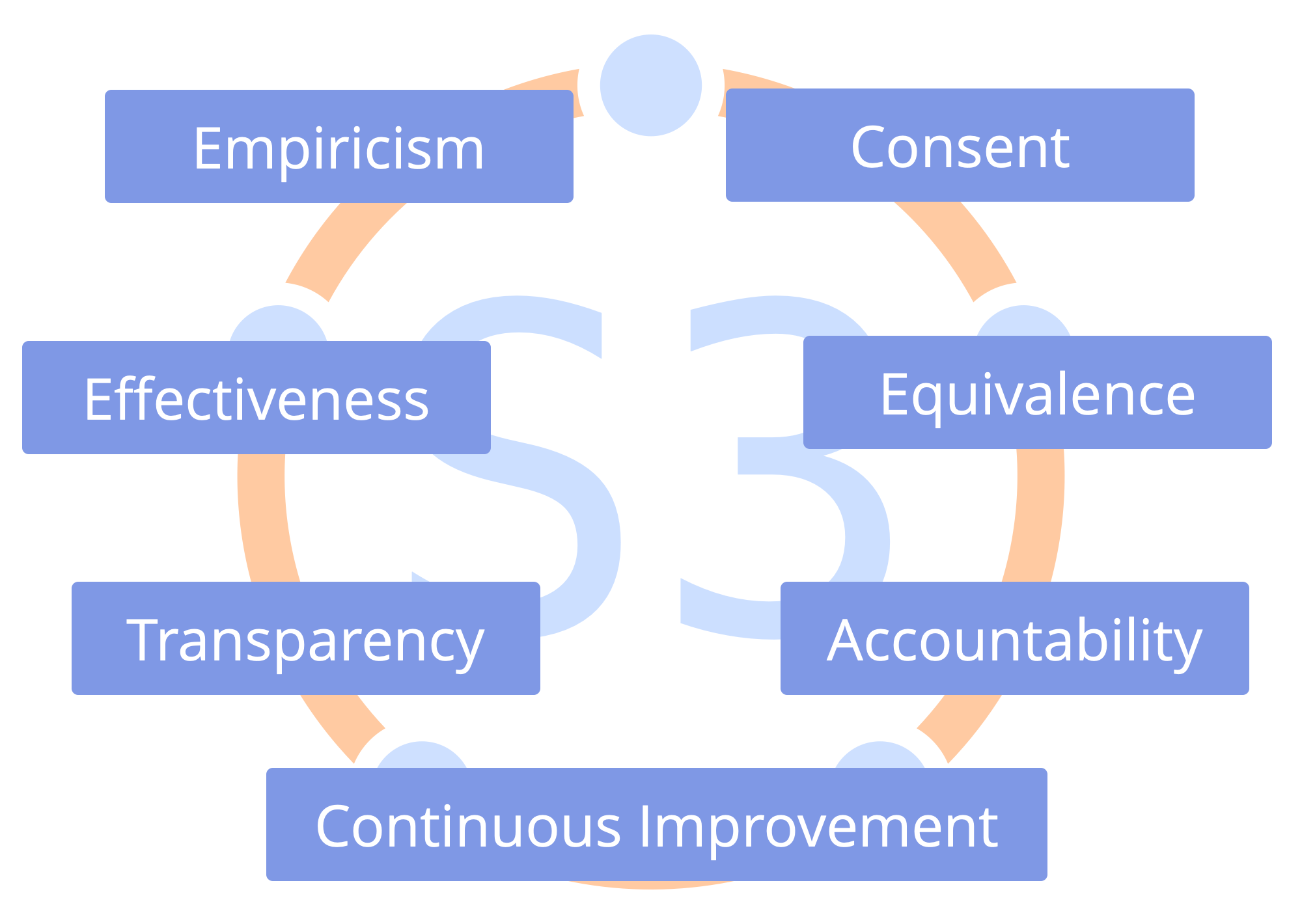

The Seven Principles

Sociocracy 3.0 is built on seven foundational principles which enable sociocratic and agile collaboration. Since the seven principles are reflected in all of the patterns, understanding these principles is helpful for adopting and paramount to adapting Sociocracy 3.0 patterns.

Practicing Sociocracy 3.0 helps people appreciate the essential value that these core principles bring – both to individuals and to organizations – and supports their integration into organizational culture.

The Principle of Effectiveness:

Devote time only to what brings you closer towards achieving your organization’s overall objectives, so that you can make the best use of your limited time, energy, and resources.

The Principle of Consent:

Raise, seek out and resolve objections to proposals, policies and activities, to reduce the potential for decisions leading to undesirable consequences and to discover worthwhile ways to improve.

The Principle of Empiricism:

Test all assumptions you rely on through experiments and continuous revision, so that you learn fast, make sense of things, and navigate complexity as effectively as you can.

The Principle of Continuous Improvement:

Regularly review the outcomes of your actions, then make incremental improvements to what you do and how you do it based on what you learn, so that you can adapt to changes when necessary, and maintain or improve effectiveness over time.

The Principle of Equivalence:

Involve people in making and evolving decisions that affect them, to increase engagement and accountability, and utilize the distributed intelligence to achieve and evolve your objectives.

The Principle of Transparency:

Record all information that is valuable for the organization and make it accessible to everyone in the organization, unless there is a reason for confidentiality, so that everyone has the information they need to understand how to do their work in a way that contributes most effectively to the whole.

The Principle of Accountability:

Respond when something is needed, do what you agreed to do, and accept your share of responsibility for the course of the organization, so that what needs doing gets done, nothing is overlooked, and everyone does what they can to contribute toward the effectiveness and integrity of the organization.

The Principle of Effectiveness

Devote time only to what brings you closer towards achieving your organization’s overall objectives, so that you can make the best use of your limited time, energy, and resources.

The principle of effectiveness invites us to think consciously about what we do and how we do things. It calls for the intentional consideration of the consequences of our actions, both now and across time, on our organizations but also on the wider environment and the world at large.

Pursuing effectiveness requires that we act with intent to minimize waste, remove impediments and, where possible, conduct ourselves in ways that over time, lead to the greatest value creation possible, through the synergy of our creativity, resources, energy and time.

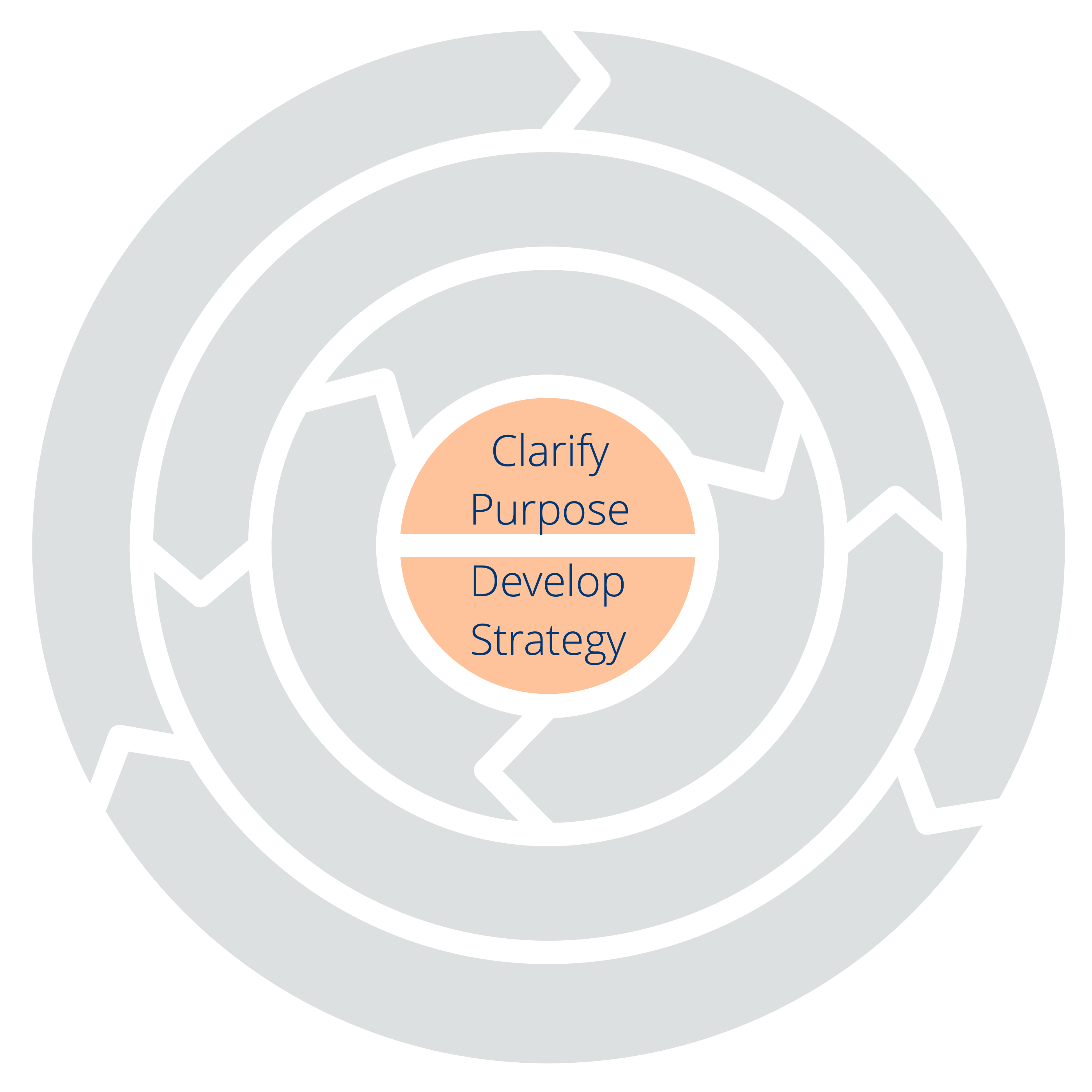

Clarify the Why

Being effective begins with getting clear about why you want to do something and establishing an approximate idea of what it is you want to achieve. Defining why the organization exists and the objectives it’s trying to achieve helps everyone understand more about what they are working toward and about how they can contribute in a meaningful way. Without this clarity, it’s hard for individuals to contextualize their work in the bigger picture. It’s also harder to qualify and quantify what brings value and in which ways.

Keep Your Options Open

There might be many ways to go about achieving your objectives and sometimes your first choice might fail to meet the need. Keep your options open to avoid getting stuck in a particular trajectory as you learn about ways to improve. Avoid converging too soon and take an iterative approach whenever you can. In complexity, find ways to test any hypotheses quickly, run multiple small experiments if possible, and travel light so that you can pivot fast.

Aim for Being Effective in an Efficient Way

Effectiveness is about achieving the desired result, while efficiency is about doing things with the least waste of your effort, resources and time. It is entirely possible to do the “wrong” thing very efficiently, so before optimizing for efficiency, ensure the outcome is what you intended. Only then look for worthwhile improvements to produce the same outcome in a more efficient manner.

Consider the Bigger Picture, Monitor, Evaluate and Learn

Be on the lookout for possible side-effects and unintended consequences before, during and after any interventions you make. Consider direct and indirect costs and negative externalities and be prepared to evolve or change your activities or objectives, based on what you learn.

There are scales of effectiveness (and efficiency) that can only be appreciated if we consider the wider context and consequences of our actions across time. Sometimes our activities might achieve the outcomes we intended in the short term but with unfavorable consequences and hidden costs that only reveal themselves across time. For example, large scale, industrial agriculture produces huge yields very efficiently but over the long-term it leads to a critical depletion of topsoil and increasing dependency on fertilizers, insecticides and weedkillers. This can be a case of a short term gain but for long term pain.

In complex environments it is sometimes hard to figure out what effectiveness would actually mean. Consider the perspective of others, even if you are making a decision for yourself. Make the most of experience and expertise distributed throughout your organization and reach out to people with alternative points of view. Running your ideas past others can help you to avoid consequences that you’d rather avoid, and identify worthwhile ways to improve.

Decide how you will measure effectiveness, and if you’re collaborating with others, develop and maintain a shared understanding of what this will mean. Having established a clear “why” and defined the outcome you intend to achieve, consider how you will measure results in a way that allows you to see how you’re progressing (and whether anything you are doing is useful at all!)

Effectiveness can sometimes only be determined in retrospect. Pay attention to and reflect on the consequences of your actions, and then use what you learn to improve your effectiveness next time.

Be Mindful of Dependencies and Constraints

Aim to free everyone up to be able to act as autonomously as possible and do what you need to do to free yourself up as well. Make any necessary dependencies between certain individuals and teams explicit, and get together to co-create and evolve a coherent system to deal with them, so that you can still deliver value fast when dependencies cannot be avoided.

Clarify any constraints in which you need to operate. What are the internal and external expectations, guidelines or rules? How do the implicit or explicit values of your organization and the wider context in which you are operating, enable or limit the decisions and actions you make? How will you operate within any specific boundaries? Who do you need to communicate with if you see an argument for changing something, or for making an exception to a rule?

Prioritize and Choose Wisely

Set priorities and stick to them unless you become aware of a reason to change. Distractions, context switching and a lack of breaks or slack time will inevitably lead to waste.

As well as getting clear on what you WILL do, be clear on what NOT to do as well and aim to resolve impediments as they arise.

The Principle of Consent

Raise, seek out and resolve objections to proposals, policies and activities, to reduce the potential for decisions leading to undesirable consequences and to discover worthwhile ways to improve.

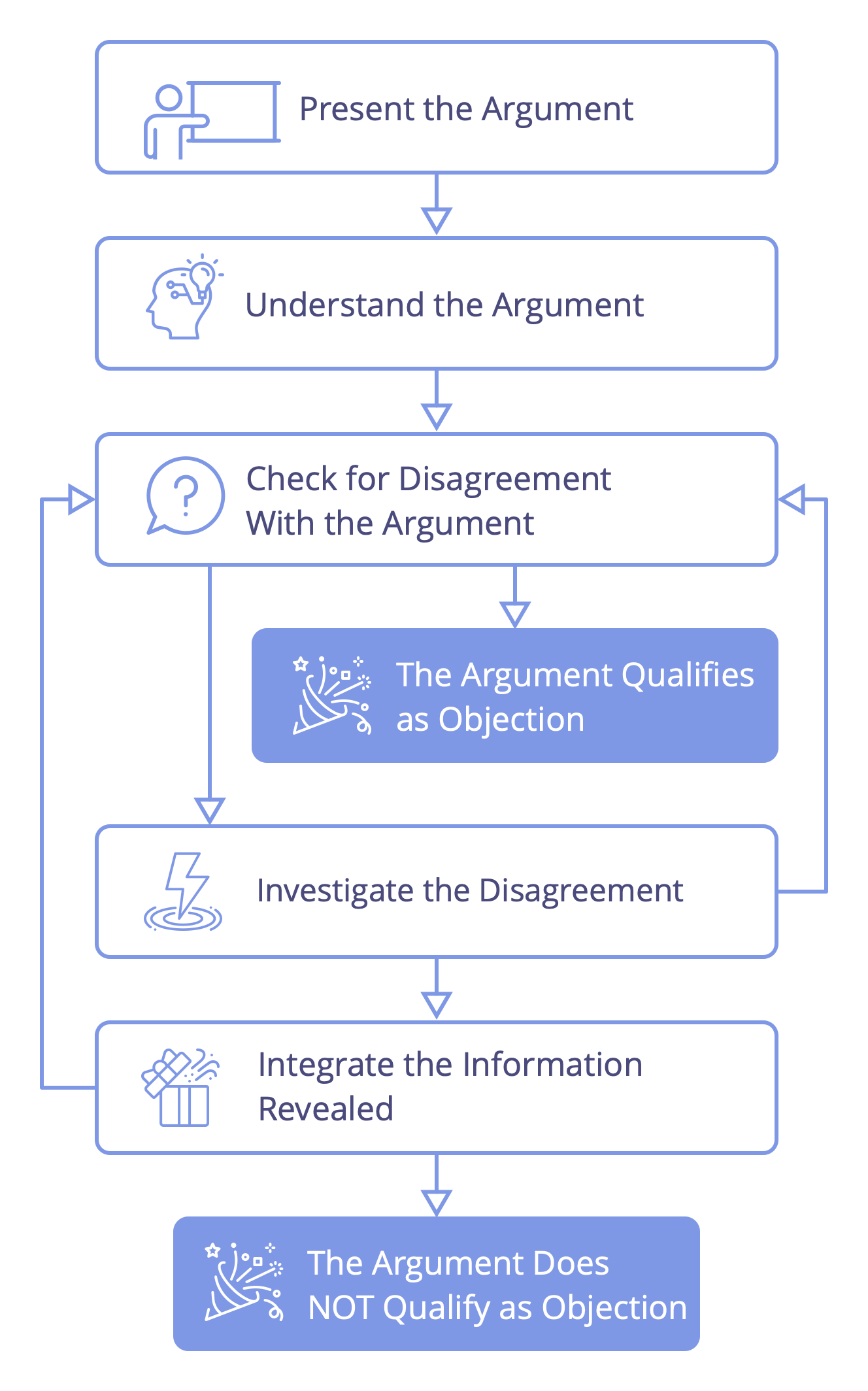

Deliberately seeking objections is a way to tap into the collective intelligence distributed throughout an organization and benefit from insights we might otherwise miss. Examining proposals, decisions, and activities through the lens of different people’s perspectives helps to identify reasons why proceeding in a specific way could lead to consequences that would be better avoided, and if there are worthwhile ways to improve things.

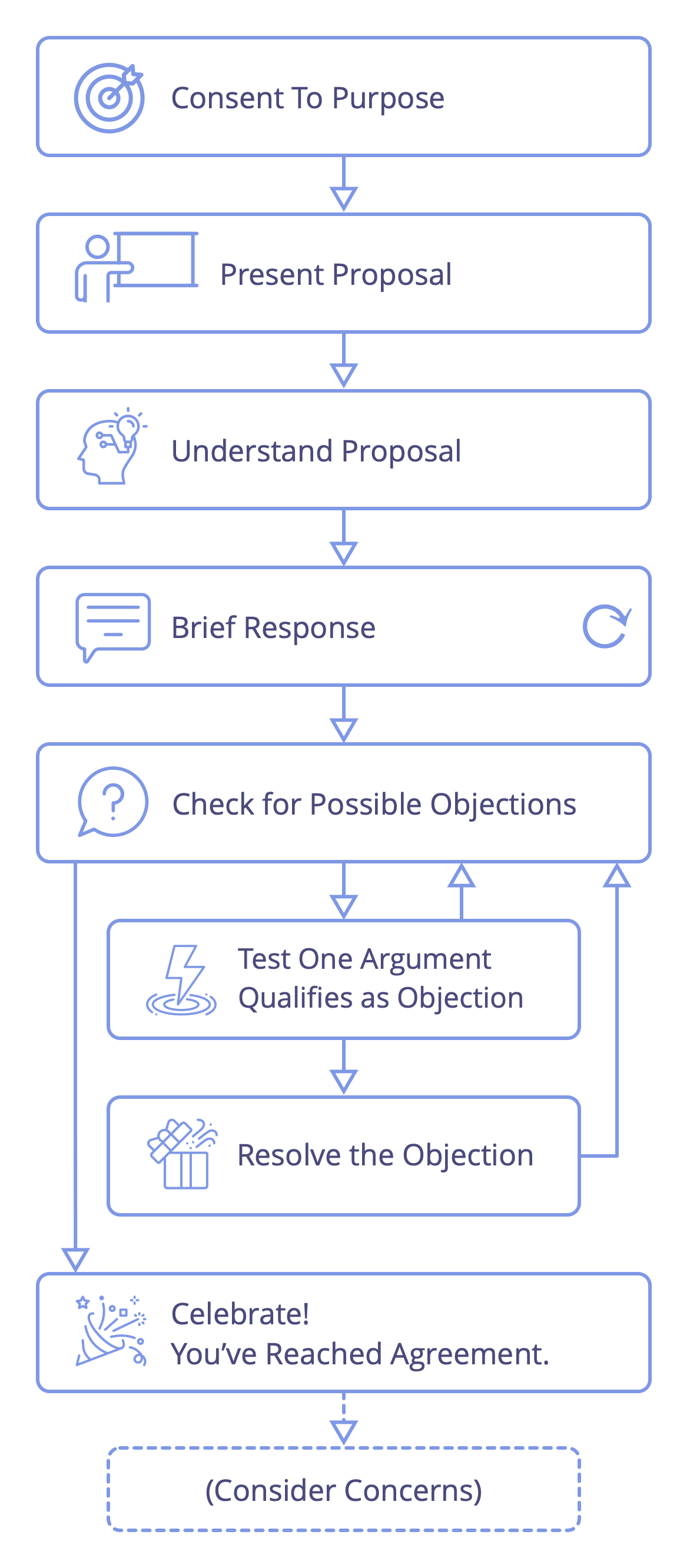

Adopting the principle of consent invites a change of focus in decision-making, shifting intent from trying to reach an agreement - “can everyone agree with this?” — toward the practice of deliberately checking for objections — are there any arguments that reveal why this is not good enough, safe enough, or that there are worthwhile ways to improve?

Consent does not mean everyone is actively involved in making every decision, as this would be ineffective. It does, however, require adequate transparency and mindfulness on the part of decision-makers to inform and involve people who would be impacted (to varying degrees), or to invite those who can bring relevant experience or expertise (see the Principle of Equivalence).

Invite Dissent

When dealing with complicated or complex matters, considering different perspectives, experience, and expertise is a simple yet effective way to develop a coherent shared understanding, out of which more effective decisions can be made.

Developing a culture that welcomes dissenting opinions and where people consider those opinions to discover any value they can bring generates greater engagement, psychological safety, and support for decisions.

Shift the Supremacy from People to Sound Arguments

When comparing the available paradigms for decision-making, the essential difference lies in where the ultimate authority for making a decision is placed. In autocratic systems, supremacy lies with an individual or a small group. In a system governed using majority voting, supremacy lies with the majority (or those who can convince the majority of their position). In a system aspiring toward consensus with unanimity, supremacy lies with whoever decides to block a proposal or existing decision. In all three of these cases, a decision is made regardless of whether the motive of those actors is aligned with the interest of the system or not.

When a group or organization chooses to abide by the principle of consent, supremacy shifts from any specific individual or group to reasoned arguments that reveal the potential for undesirable consequences that would be better avoided or worthwhile ways to improve. This way, people — regardless of their position, rank, function, or role — are unable to block decisions based solely on opinion, personal preference, or rank, and they can be held to account in the case that they do. Consent invites everyone to at least be reasonable, while still leaving space for individuals to express diverse perspectives, opinions, and ideas.

Distinguish Between Opinion or Preference, and Objections

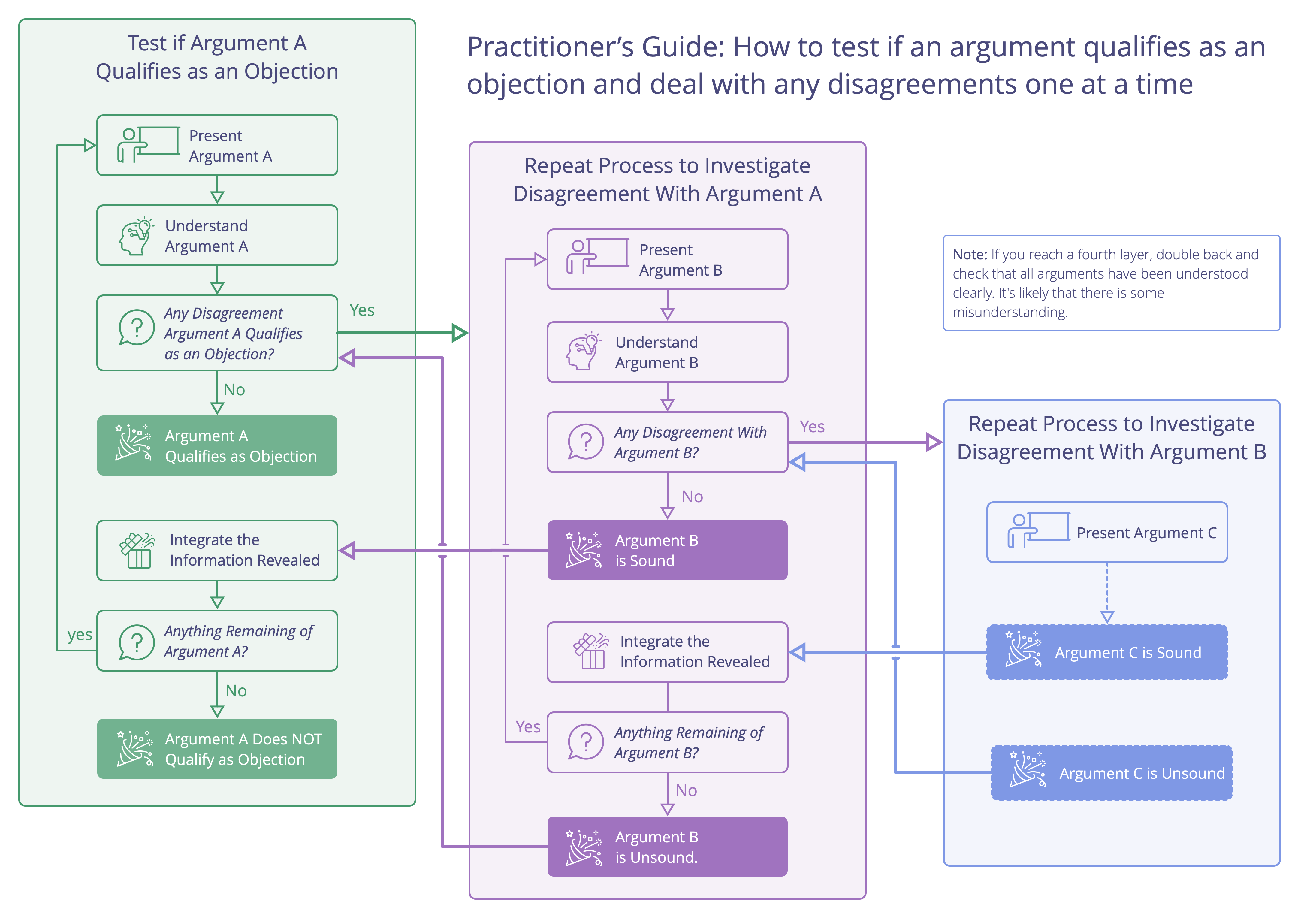

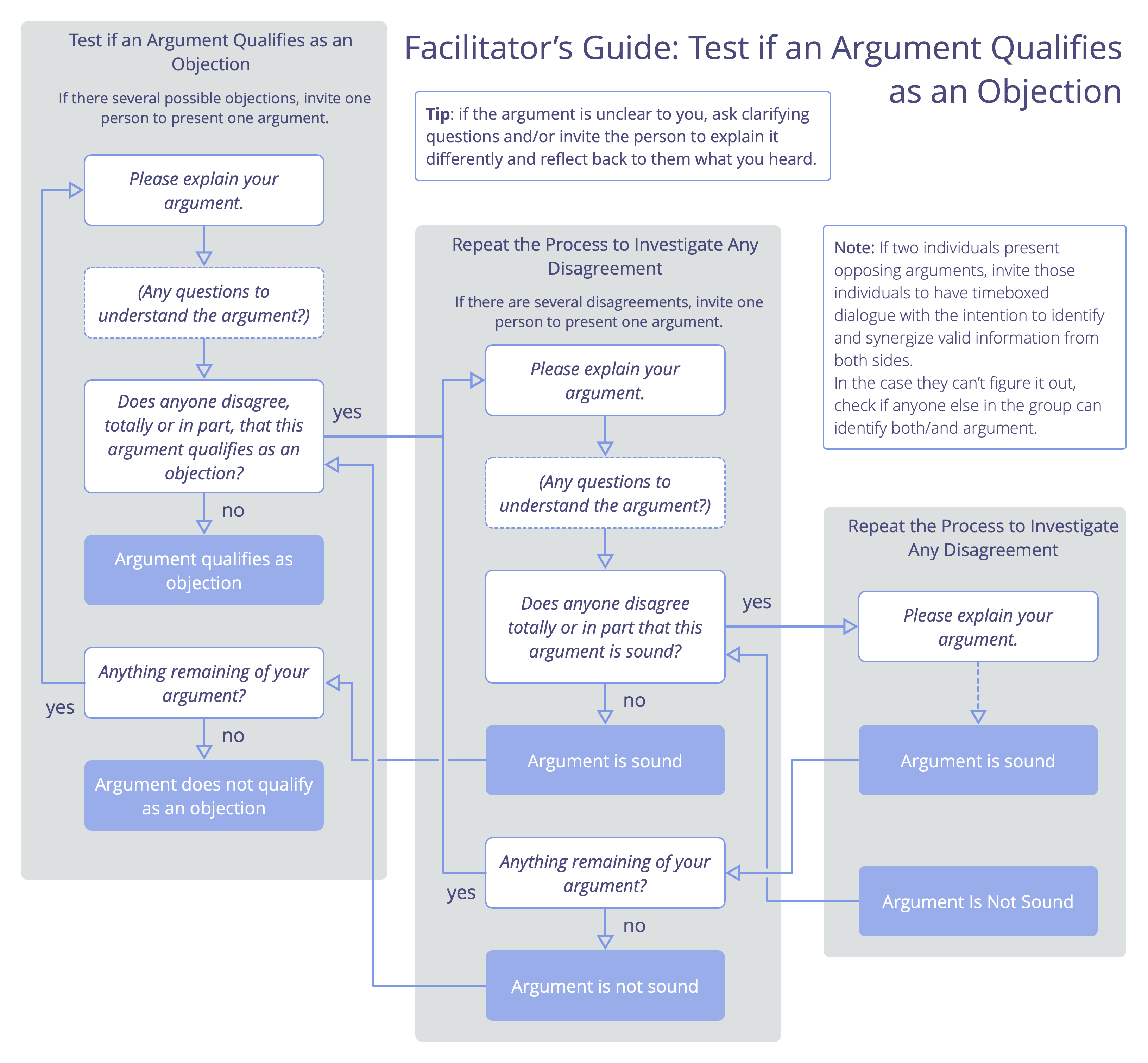

Consent draws on the intelligence distributed throughout an organization, not only by inviting people to raise possible objections, but by inviting people to then examine those arguments, rooting out any that are unfounded, evolving those they discover to be only partly true, and revealing those that are valid objections. So it’s typically a good idea to test if arguments qualify as objections and only act on those that do. This helps avoid wasting time on arguments based merely on opinions, personal preference, or bias.

Arguments that qualify as objections — at least as far as stakeholders can tell — help a group in directing their effort toward making changes in those areas where it’s necessary or worthwhile to adapt and improve. Incremental improvement based on discovery and learning is built into consent and is an inevitable consequence of adopting the principle.

Adopting the principle of consent shifts the aim of decision-making toward identifying a solution that’s good enough for now, and where there are no obvious worthwhile improvements that would justify spending more time. This approach is far more effective than trying to arrive at a consensus with unanimity, where the aim is often to accommodate everyone’s personal preferences and ideas.

Integrate Learning from Objections

Objections inform people of things that can be improved. Resolving objections typically means evolving (proposed) policies and changing activity in ways that render that argument void. Sometimes, however, having considered an objection, it might be realized that on balance and for some reason or other, it’s more advantageous to leave what was objected to unchanged. Ultimately, considering an objection and determining what, if anything, is worthwhile doing to resolve it involves weighing up pros and cons, both in relation to the specific situation a proposal, an existing decision, or an activity is intended to address, but also in the context of the organization as a whole. In complexity, there are typically no perfect or entirely correct decisions, only those that (for now at least) appear good enough for now and safe enough to try. Often, all that is needed is a good enough next step, which allows us to learn empirically and adapt and evolve the decision over time.

This approach of incremental learning draws on the diversity of knowledge, experience, and expertise distributed throughout an organization. It helps to shift from a paradigm rooted in binary thinking and polarization (either/or) to a continual process of synergy (both/and), which over time fosters stronger relationships between peers as well.

The Contract of Consent

Adopting the principle of consent in a team, or the organization as a whole, has implications for how people approach decision-making, dialogue, and activity. Consider making this implicit contract of consent explicit, to support members of the organization to adopt and apply the principle of consent:

- In the absence of objections to a proposal or decision, I intend to follow through on what’s been agreed to the best of my ability.

- As I become aware of them, I will share any possible objections to proposals, decisions, or current activities with those directly responsible for them.

- I’ll actively seek out and consider objections to proposals, policies, and activities that I’m responsible for, and I’ll work to resolve those objections if I can.

- I’ll actively consider policies that are due for review that I’m affected by or responsible for, to check for any possible objections to the prospect of continuing with that policy in its current form.

The Principle of Empiricism

Test all assumptions you rely on through experiments and continuous revision, so that you learn fast, make sense of things, and navigate complexity as effectively as you can.

Empiricism — the foundation of the scientific method — is an essential principle to embrace if we’re to navigate effectively in a complex world. Not only are the environments in which organizations operate complex but an organization is in itself a complex adaptive system. Knowledge about an organizational system and its interactions is often tentative and highly dependent on context.

Empiricism can help us to increase certainty and reduce self-delusion, so that we can make the best use of our time. In our attempts to make sense of things and to have a sense of certainty about what is happening, why it’s happening, what should happen next and what’s needed to achieve that, we often draw conclusions without checking if the assumptions they are built on are true and accurate. In complexity, what we perceive as causation can often turn out to be mere correlation or coincidence, and the outcomes of interventions we make will always lead to some consequences we couldn’t predict.

Observing and probing systems, and making use of experimentation to inform an iterative approach to change, supports ongoing learning and helps an organization continuously develop to remain effective and responsive to change.

Clarify Your Hypothesis

A hypothesis is a tentative explanation of a relationship between a specific cause and effect that is both testable and falsifiable. It provides a starting point for experiments that prove or disprove that hypothesis.

In the context of organizations, you might develop hypotheses about how a change to a work process or to the organizational structure would improve effectiveness or reduce cost. Or about how rescheduling a meeting would increase engagement, or making a certain change to a product would attract a new customer segment while keeping existing customers happy, and so on.

When faced with uncertainty, it helps to make any questions and assumptions you have explicit and describe a clear hypothesis that allows for answering those questions and validating if your assumptions are true. A vague or ambiguous description will make assumptions hard or even impossible to test, and trying to test too many assumptions at once, might set you up on a long path where you learn little of value. Less is often more.

One vital skill to develop when designing experiments is the ability to distinguish between established knowledge and mere assumptions. By acknowledging what you don’t know yet and what you assume to be more or less true, you can identify questions and assumptions around which to build a hypothesis.

In complex domains, a hypothesis-driven approach relies on experiments to validate or disprove hypotheses, so that you can find viable ideas or falsify them fast. Making sense of things through experimentation, not only enables you to more effectively achieve what you need or desire but it can also help you to validate assumptions you have about which objectives are worthwhile pursuing to start with.

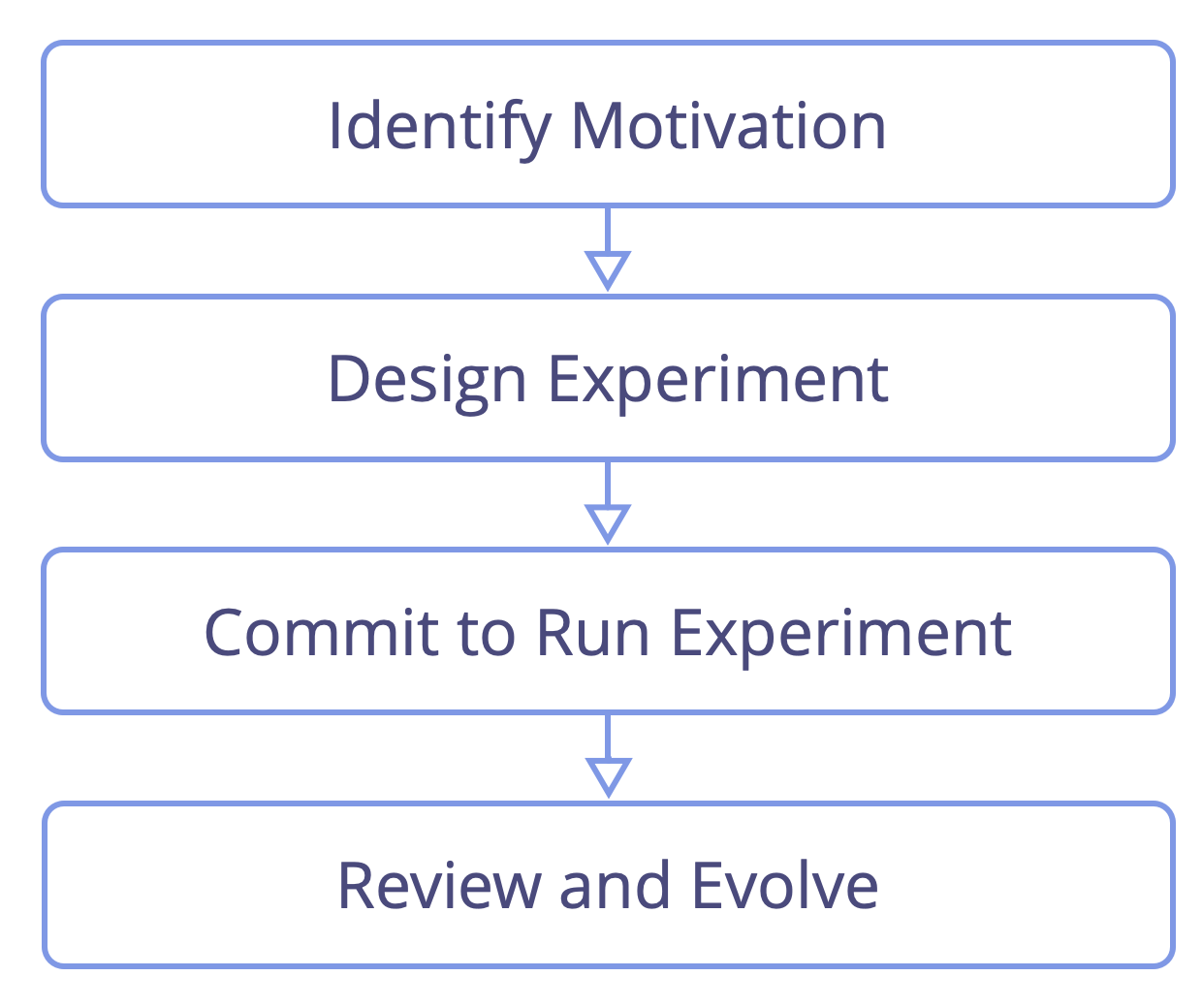

Design Good Experiments

An experiment is a controlled test designed to prove or disprove a hypothesis. Experiments provide you with validated learning about how to better respond to the challenges and opportunities you face. Outcomes often provide you with the opportunity to refine your hypothesis, or even develop new hypotheses that you can then test with further experiments.

Before you start an experiment, it’s important to fully define and document it. In the context of an organization, a good experiment will consist of a list of things you need to do, and if helpful, how you need to do them, as well as a list of variables you will track before, during and/or after the experiment.

Define and document specific thresholds for success and failure of the experiment related to your variables and add details about this to your evaluation criteria. In particular, consider what you would accept as evidence that your hypothesis is false. While an experiment is running, avoid making changes to it, and if you do change something, document those changes, otherwise your measurements may become meaningless. It is vital that you measure before starting the experiment to ensure that the threshold for success is not already met because you made an error in your experiment’s design.

Treat Decisions as Experiments

In a complex system, it is impossible to predict all of the ways in which that system will react to a particular intervention of change. Because of this you can apply the concept of experimentation to the way you approach decision-making as well. It’s valuable to view all significant operational and governance decisions you make as experiments, and to document the intended outcome and evaluation criteria in each case. Make one decision at a time, starting with what appears to be an appropriate or logical starting point and evolve those decisions iteratively, based on what you learn.

The Principle of Continuous Improvement

Regularly review the outcomes of your actions, then make incremental improvements to what you do and how you do it based on what you learn, so that you can adapt to changes when necessary, and maintain or improve effectiveness over time.

Whereas the principles of Empiricism and Consent reveal opportunities for learning, Continuous Improvement relates to what we do with what we learn. Continuous Improvement applies to how we conduct our operations, but also to governance. Everything from the evolution of strategies, policy, processes and guidelines, to the development of products, services, competencies and skills, attitudes and behavior, chosen values and tools, all can be continuously improved.

####Take an Iterative Approach to Change

Evolution is often more effective and more sustainable than revolution which is rarely necessary or worthwhile unless you fail to continuously improve a system when it’s needed. Especially in a complex environment, making many changes to a system at the same time can lead to a mess that is difficult to fix. Consequences resulting from larger interventions are often hard to measure effectively, especially in complexity, and the relationship between cause and effect will be difficult, if not impossible to determine and evaluate.

Instead, consider changing things incrementally whenever you see an opportunity for a small and worthwhile improvement, significantly reducing the need for a large intervention. This will help you to effectively adapt to changing environments, keep your organization and systems fit for purpose, and prevent things from descending into a state that is costly or even impossible to repair.

Even when a large change is needed, go step by step, figuring out how things need to be and adjust what you’re doing based on what you learn. With small changes, assumptions can be tested quickly and failure is more manageable. When a small experiment fails, you can learn fast and if necessary, use what you learn to develop a better experiment. When a large experiment fails, a lot of time and effort might be spent without learning much at all.

Be aware that if you change several things at the same time, you might not be able to determine which of them lead to the effects you see, so aim for one or only a few concurrent changes at a time.

Monitor, Measure and Change Things Based on What You Learn

Define the intended outcome you expect a change will lead to and be clear on how you will evaluate whatever occurs. When making changes, be clear about the specifics of what you want to improve. What positive consequences do you want to amplify and what negative consequences do you want to dampen?

Monitor the consequences of your actions and reflect on what you learn. Pay attention to what actually happens and whether or not the results of your interventions reflect your assumptions and intentions. This will help you keep track of whether or not your changes led to improvements at all.

Remember that even if things don’t turn out as you expect sometimes, this doesn’t necessarily mean that the results are negative. Sometimes things turn out differently to how we’d assumed or intended. All outcomes help us learn. Be open to whatever happens, consider the pros and cons of any unintended consequences that emerge and acknowledge when it would be beneficial to do things differently, or to aim for different results.

The Principle of Equivalence

Involve people in making and evolving decisions that affect them, to increase engagement and accountability, and utilize the distributed intelligence to achieve and evolve your objectives.

Equivalence is important in organizational systems, precisely because people are not equal in a variety of ways, and depending on the context.

Equivalence increases engagement by giving people affected by decisions the opportunity to influence those decisions to some degree.

By including people in making and evolving a decision that affects them, they gain a deeper understanding of the resulting decision, the situation it’s intended to address, and the pros and cons that have been weighed in the process. It also helps to keep systems more open and transparent and reduces the potential for information vital to the decision being overlooked or ignored. Depending on the level of involvement, people might also have the opportunity to shape things according to their preference, and in any case, participation in the decision-making leads to a greater sense of ownership over what is decided.

People are more likely to take responsibility for following through on decisions when they are involved in making them. This is further reinforced when ensuring affected parties have influence in adapting those decisions later, should they discover reasons why a decision is no longer good enough, or if they discover a viable way to improve something.

Developing decisions collaboratively fosters a stronger sense of ownership and commitment among stakeholders. In contrast, decisions made by others may be supported or appreciated to varying degrees by those affected, depending on individual perspectives and preferences.

Some decisions will affect a large group of people, e.g., an entire department, or even the organization as a whole. Including those affected in the decision-making process will yield benefits that reach far beyond the decision in question. People will build connection, trust, and a greater sense of community and belonging. For effectively involving a large number of stakeholders in the decision-making process, you can use a variety of group facilitation techniques and online tools.

Delegate Responsibility and Authority to Influence

To become or remain effective, organizations of any size benefit from distributing work and the authority to influence decisions relating to that work. Doing so helps to avoid unnecessary dependencies, so that people can create value unimpeded, without getting bottlenecked, waiting on a decision-making hierarchy or on the input of others who are more distant from the work.

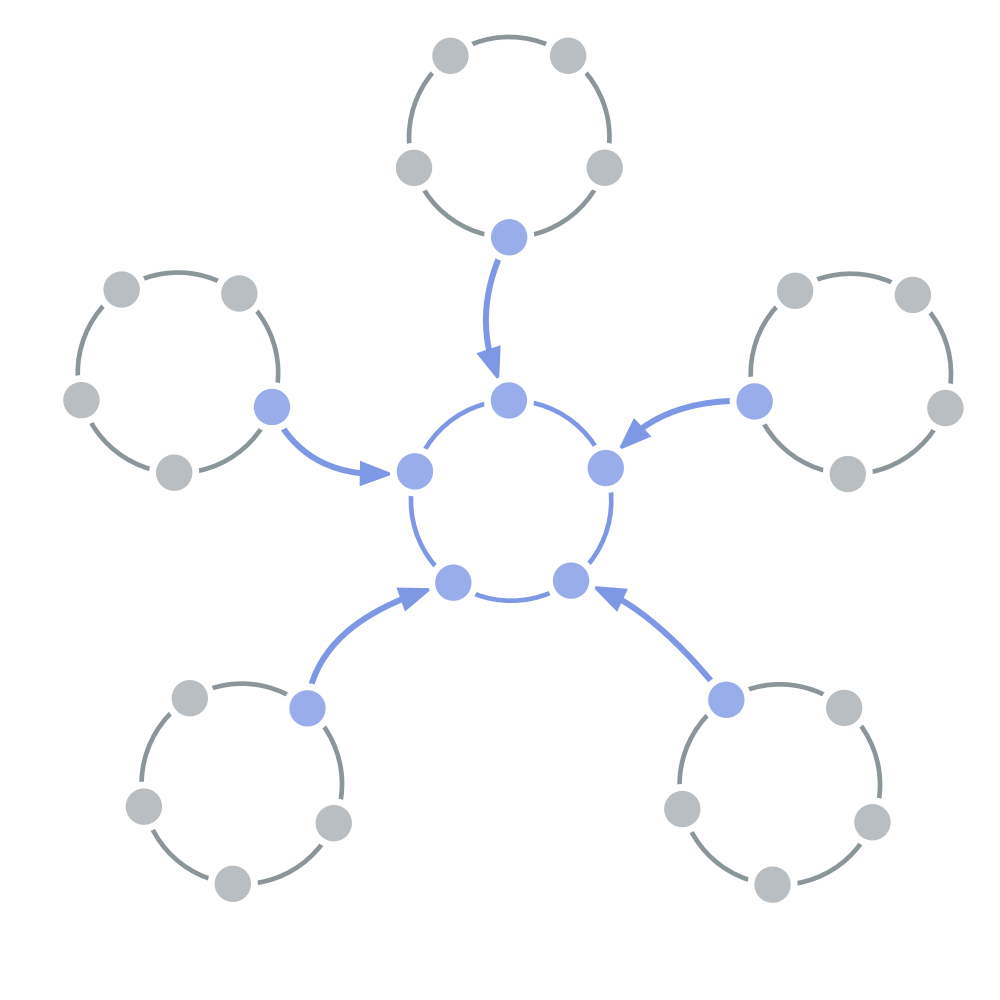

For making or evolving policies that affect a large number of people, however, involving everyone fully from end-to-end, requires a lot of time and rarely makes sense. In such cases, delegating the responsibility to a smaller group with relevant experience and expertise helps keep the process efficient. But then, by also keeping all affected parties informed about progress and involving them in procedures to the degree that is worthwhile, it’s possible to draw on a wider field of collective intelligence that can help improve the effectiveness of decisions as well. At the very least, possible objections from all stakeholders can still be quickly identified by checking for possible objections to proposals or in-principle agreements, and resolving those arguments that qualify. This helps to build and maintain a sense of ownership over those decisions, and reduces the potential for resistance and or resentment to grow.

Furthermore, periodically rotating who takes a lead in decision-making helps build trust, accountability, and a more widely shared understanding of the context in which decisions are being made, because a growing number of people will gain experience in that role.

Consider Who Should Be Involved and How

Everyone throughout an organization is impacted by all decisions to some degree, because each decision will impact the whole in some way. Equivalence in decision-making doesn’t mean everyone needs to be involved in every decision all of the time. Nor does it mean that everyone has to have the same amount of influence in every context where they are affected. Equivalence means ensuring that those affected by decisions are at least able to influence those decisions, on the basis of arguments that reveal unintended consequences for the organization that are preferable to avoid, and/or worthwhile ways for how things can be improved. Put another way, the minimum requirement for equivalence to exist is to hear and consider any possible objections raised by people affected by decisions, and work to ensure that those objections are resolved.

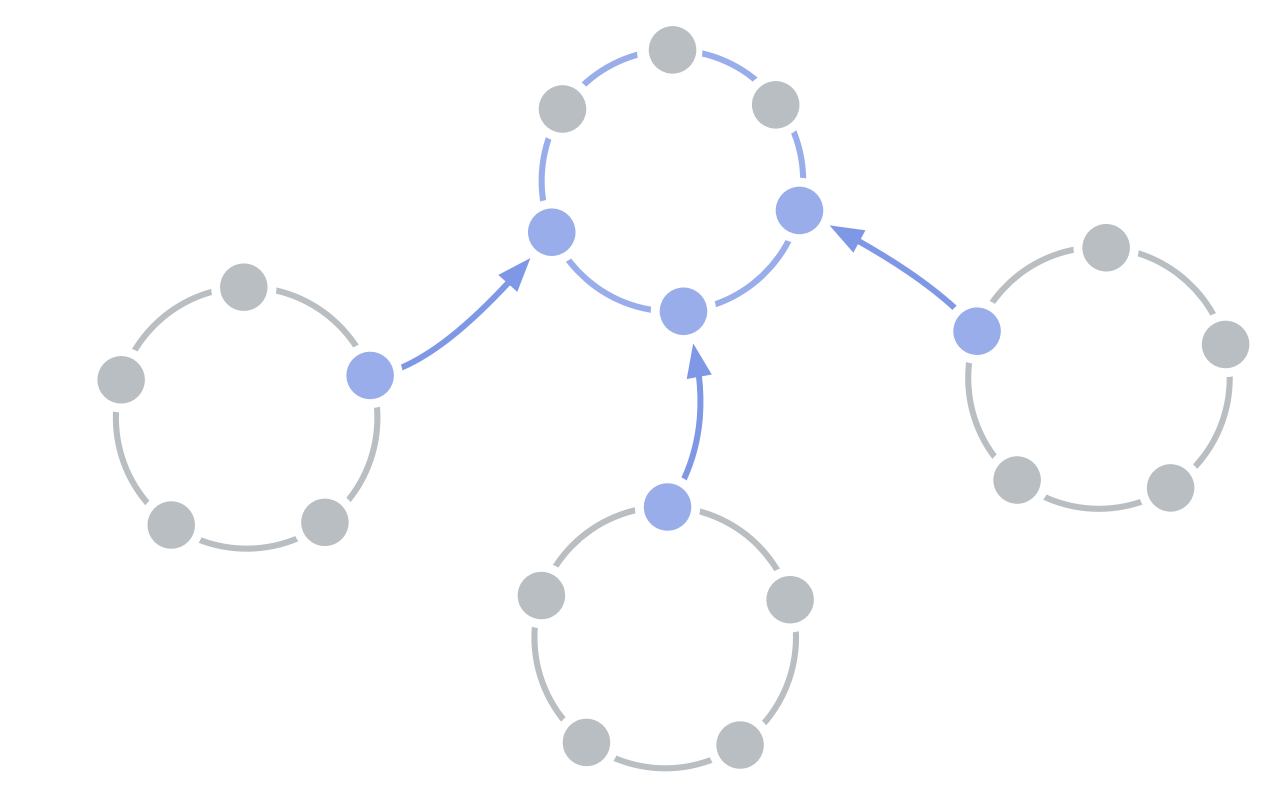

The degree of worthwhile involvement is context-dependent. At one end of the spectrum, it might be enough that decisions affecting others are made initially by an individual or a smaller group and that these decisions are then tested for any objections from those affected afterwards. On the other end of the spectrum, equivalence could manifest as a fully collaborative process where those affected participate in decision-making from end-to-end. A middle road is a participatory approach that keeps people informed about progress and invites specific input at various stages along the way.

Equivalence needs to be balanced with Effectiveness, enabled through Transparency and constrained by Consent, for it to function at its best. It’s valuable to weigh up the benefits of more or less involvement, versus the cost in terms of resources, energy and time.

For any decision of significance, it’s good to ask yourself who, if anyone, should be involved, and to what degree? Consider those who will be directly or indirectly impacted and those who will have responsibility for acting on what you decide. While not directly related to Equivalence, it might also be prudent to consider those who are not obviously affected by a decision, but who could contribute with their influence, experience, and expertise.

Make the necessary information available

For people to contribute in an effective way, they need access to relevant information relating to the decision in question. It’s helpful to develop a system for visualizing important decisions and broadcasting about them to others. Visibility and the option for open dialogue about what’s going on in the organization help to build shared understanding, which, in turn, contributes toward more effective decisions being made.

Invest in Learning and Development

When involving people in decision-making, everyone understanding what objections are — and how they are distinct from concerns, opinions, or preferences — will help people contribute to decisions in more meaningful and effective ways. Put in place ways to gather any possible objections that people raise and develop a system to easily make them available to the people directly responsible for making and evolving those decisions.

In the case where people are responsible for making and evolving policies together on a regular basis, invest in everyone developing the necessary competence and skills. This includes learning basic communication skills and developing fluency in whichever decision-making processes you use.

Invite External Influence

Some decision-making will be improved through including a range of perspectives and expertise. When looking for people with a worthwhile perspective to bring, consider the wider organization and your external environment too. Who has valuable expertise or experience from elsewhere in the organization, and who are your customers, investors, and other stakeholders? All of these people are affected in some way by the consequences of the decisions you make. As well as being open to considering their suggestions and points of view, there might be times when actively inviting their opinion or involving them in certain decisions you need to make will inform you of better ways to achieve your goals.

The Principle of Transparency

Record all information that is valuable for the organization and make it accessible to everyone in the organization, unless there is a reason for confidentiality, so that everyone has the information they need to understand how to do their work in a way that contributes most effectively to the whole.

Transparency in an organization helps people understand what’s going on, what to expect and why things are done the way they are. It reduces uncertainty, supports trust and trustworthiness and fosters accountability.

Adequate transparency means that people either have direct access to the information they need, or that they at least know where to go or who to ask, to get access to it. Transparency helps everyone understand when they can safely and effectively decide and act for themselves and when they need to involve others to respond to dependencies they share.

Transparency supports us to learn from, and with each other. It helps to reduce the potential of small problems growing into big ones because we are more likely to spot mistakes and negative unintended consequences more promptly.

Transparency facilitates the ongoing development and maintenance of a coherent and adaptive learning organization. Having access to relevant information helps us to quickly identify important needs and changes and respond fast.

Clarify Motivation for (More) Transparency

Transparency is a means to an end, not an end in itself, so if you’re looking to increase transparency in your organization, take the time to clarify the reasons why. What are the challenges you are trying to solve by introducing more transparency and/or what are the opportunities you wish to pursue?

Introduce more transparency into your organization as a way to support learning and to free people up, not as a way to control them. Use it as a way to improve performance, not leave people feeling unsafe to do anything because they are anxious about being watched. Transparency can enable co-creation and innovation but in a context where failure is treated as negative, rather than an opportunity to learn, it will impede people’s willingness to take risks and experiment.

Consider Reasons for Confidentiality

Be clear about information that is inappropriate to share. While secrecy can be associated with illicit or dubious affairs, there are many legitimate reasons for confidentiality in organizations. Sometimes secrecy is necessary, for example, protection of people’s personal data and affairs, security of assets or protection of intellectual property that helps an organization achieve its goals.

Identify What Information Is Valuable to Record and Share

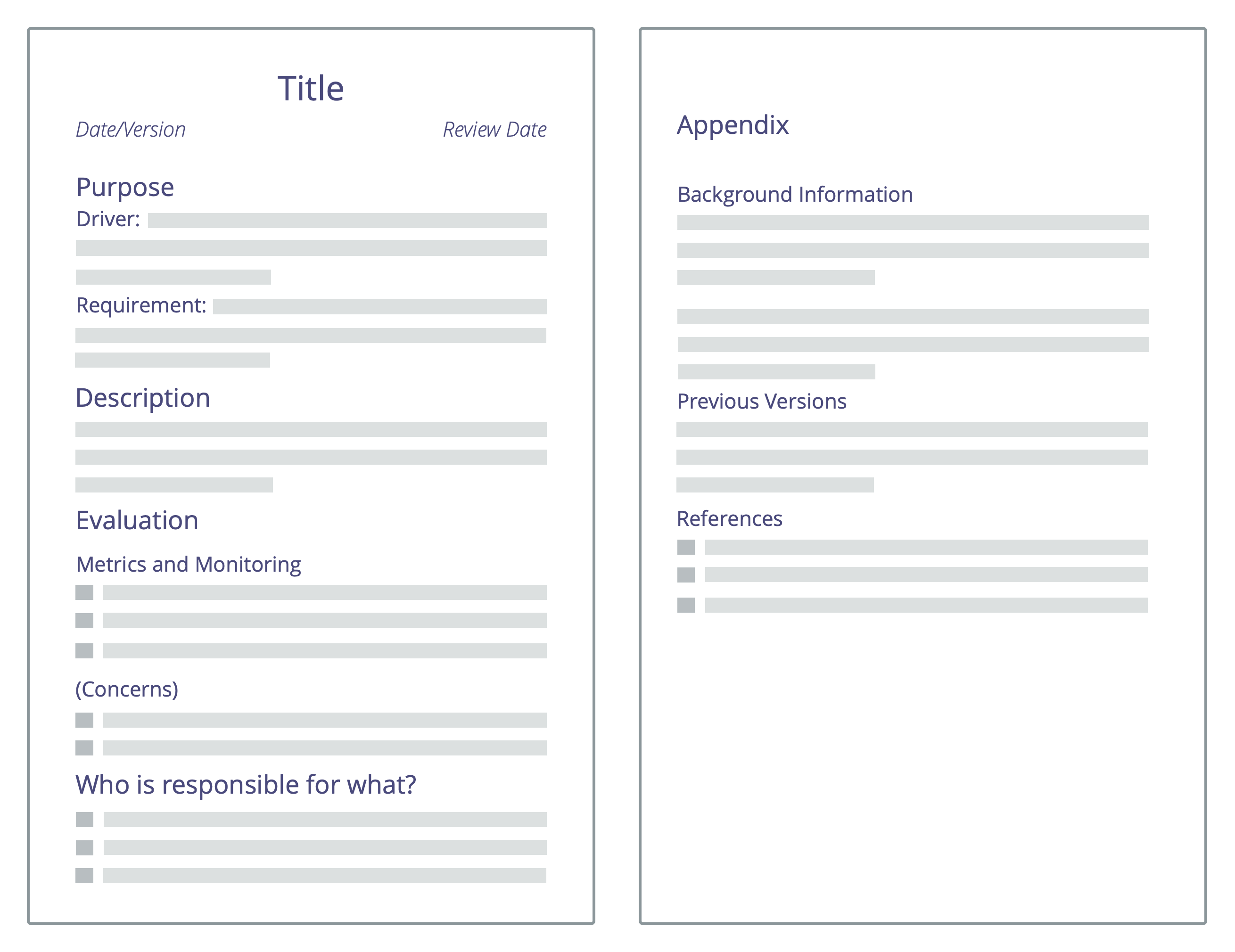

Consider carefully what information is worthwhile to record. Valuable information worth recording typically includes:

- decisions that have been made, along with the information they were based upon, who made them and the reasons why they were made

- any information that supports people to make effective decisions, such as details about the context, possibilities explored and any important constraints

- information that helps with evaluating progress and outcomes, including evaluation criteria, metrics, descriptions of intended outcomes and details of any hypotheses upon which decisions are being made

- information that reduces uncertainty and supports the development of trust, such as finances and future plans

- useful insights and learning

- meeting minutes

Create and Maintain a Coherent System for Recording Information

Documenting relevant information in a way that is coherent and accessible is an ongoing task that relies on everyone in the organization playing their part. Developing a system for recording and sharing information and keeping it up to date takes time and effort. Choose tools that make it simple to create, update, and cross-reference records, as well as to search and retrieve information when it’s required. Make clear which information is recorded and updated, by whom and when, and structure records accordingly. Take the time to regularly check through your records, ensure your system remains helpful and keep an archive of historical information for reference.

The Principle of Accountability

Respond when something is needed, do what you agreed to do, and accept your share of responsibility for the course of the organization, so that what needs doing gets done, nothing is overlooked, and everyone does what they can to contribute toward the effectiveness and integrity of the organization.

Whenever we are part of a system (e.g. an organization, a community, family or state) the consequence of our actions or inaction will impact others in that same system for better or worse. Therefore we carry a certain amount of responsibility for the wellbeing of the system.

In particular, when we choose to become part of an organization, we enter into a transactional relationship with others, where we can expect to receive something in exchange for taking care of one or more specific needs the organization has.

The promise we make to take responsibility for things that need doing, creates a dependency between us and those who depend on the fulfillment of that promise.

Acknowledge Shared Accountability

The consequences of our action or inaction will affect the organization in some way, so by becoming part of an organization we are taking some responsibility for the wellbeing of the whole. Many responsibilities within an organization are hard to anticipate, are undefined and are undelegated. Therefore when members of an organization recognize that they share accountability for the organization as a whole, they are more inclined to step up, bring attention to important issues, and take responsibility for things when needed. Problems and opportunities are more likely to be acknowledged and dealt with and you reduce the risk of developing a culture of looking the other way, or worse, a culture of blame.

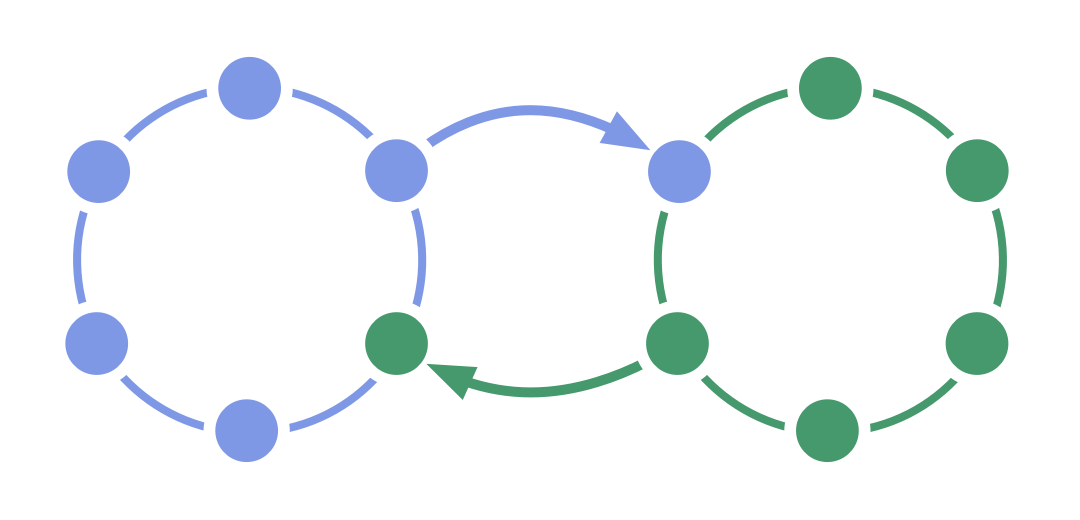

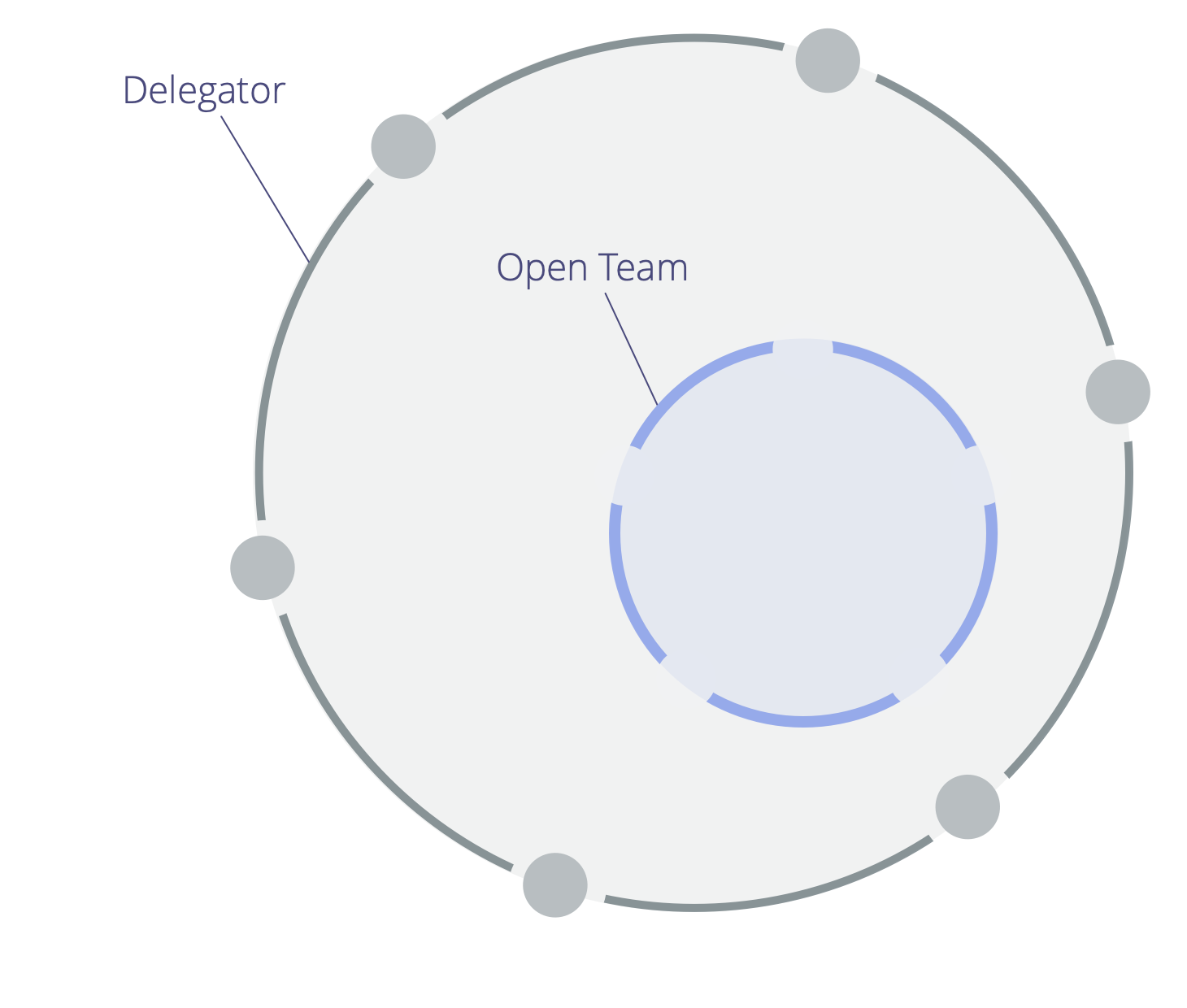

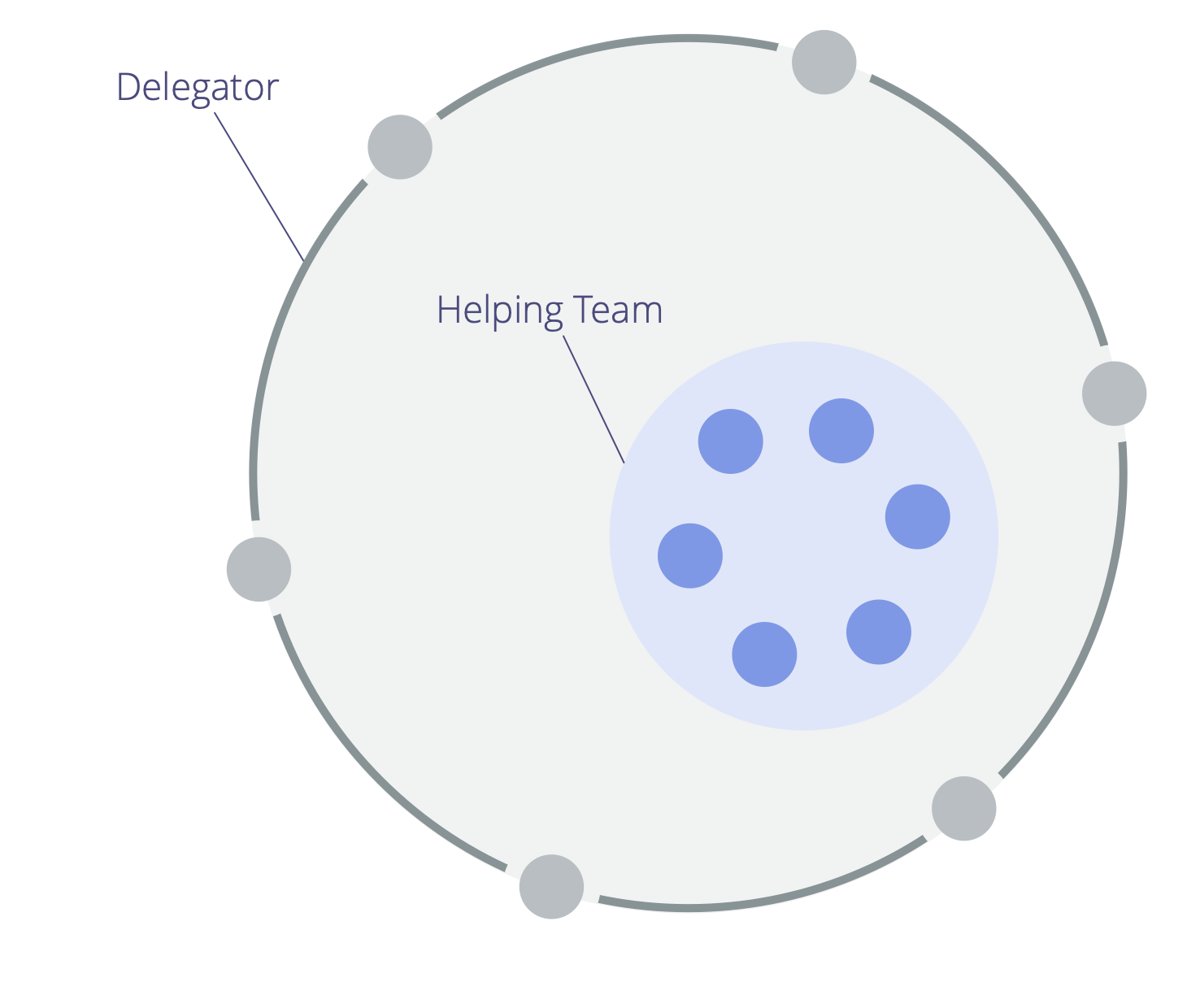

Many responsibilities are typically distributed throughout an organization by way of delegation, meaning that people take responsibility for specific work and decision-making. Whenever a responsibility is delegated by one party (the delegator) to another party (the delegatee), accountability for results is shared between both parties. This is because either parties’ choices and actions (or inaction) will impact results. Furthermore the delegator is accountable for their decision to delegate these responsibilities, and for their decision about whom to delegate them to.

While it’s typically productive for delegatee(s) to take the lead in deciding how to take care of their domain, regular communication between delegator and delegatee(s) provides a broader scope of perspective which in turn, supports strategic development and the effective execution of work.

When people consider themselves accountable only for those things that impact their immediate sphere of responsibility, many of the things that would require attention but have not been delegated to anyone in particular, or that appear to be someone else’s problem to solve, would get missed.

Whenever you see an important issue, make sure it’s taken care of, either by bringing it to the attention of others who will deal with it, or by dealing with it yourself.

Make the Hierarchy of Accountability Explicit

Most organizations have a hierarchy of delegation and therefore a hierarchy of accountability. This means that accountability for outcomes is distributed throughout the organization, while overall accountability for the integrity of the organization rests with whomever takes legal responsibility for that organization as a whole. In many organizations today, this generally points back up a leadership hierarchy to wherever the buck stops. However, in other contexts, like a community for example, overall accountability lies equally with everyone who is involved.

Whatever your particular organizational context, making the hierarchy of accountability explicit is useful because it reveals the relationship between delegator and delegatee(s).

Move From “Holding to Account” to Self-Accountability

The principle of accountability applies to everyone. It promotes a shift from being held to account by someone — which often leads to a culture of fear and blame — towards a culture of self-accountability where everyone acknowledges the impact of their actions and inaction on others, and on the system as a whole, and acts accordingly. In your relationships with others, it relates to making and following through on commitments you make, managing expectations, doing what you agree to and answering for when you don’t.

Create Conditions That Enable Accountability to Thrive

Merely clarifying what people can and cannot do is not enough to encourage a culture where accountability is embraced. In fact, alone, this can have the opposite effect. To increase the level of self-accountability in an organization there are various factors that can help:

- Involvement: the more that people are able to influence decisions that affect them, the greater their sense of ownership will be, and the greater the likelihood that they will share a sense of accountability for the results (see also: The Principle of Equivalence)

- Access to information: when people have the opportunity to find out what is going on in the organization and why certain decisions are made, they can figure out how they can best contribute to the whole and be an active and artful member of the organization (see also: The Principle of Transparency)

- Safety to disagree: when people are free to express their opinions and learn how to listen and disagree in constructive ways, the organization can rely on a broader scope of perspectives, experiences and expertise, and people will feel more psychologically safe and in control. (see also: The Principle of Consent)

Make Implicit Responsibilities Explicit

When responsibilities are unclear, it can lead to mistaken assumptions about who is responsible for what, double work, people crossing important boundaries, or failing to take action in response to important situations. At the same time, when clarifying responsibilities, it’s important to avoid over-constraining people because doing so limits their ability to make important decisions, innovate and act. This leads to a reduction in their willingness to accept accountability.

Too much specificity or too much ambiguity around the scope of authority people have to influence can lead to hesitation and waste. And in the worst case it can mean that important things don’t get dealt with at all.

Clarifying domains provides a way of explicitly delineating areas of responsibilities and defining where the edge to people’s autonomy lies.

Encourage Self-Accountability

To encourage a culture with a high level of self-accountability, do your part in creating a working environment where people voluntarily take on the following responsibilities:

- Act within any constraints governing the domains you are responsible for. This includes policies related to the organization itself, to the teams you are part of, and to the roles you keep.

- Act in accordance with any explicitly defined organizational values.

- Be transparent and proactive in communicating with those you share accountability with, if you realize that adhering to what you have previously agreed to is no longer the most effective course of action.

- Find others who can help you if you discover you’re unable to take care of your responsibilities.

- Break agreements when you are certain the benefit to the organization outweighs the cost of waiting to amend that agreement first. In such cases, take responsibility for any consequences, including following up as soon as possible with anyone who is adversely affected.

- Speak up if you believe that a proposal, policy or activity can be improved in a worthwhile way, by raising possible objections with whomever is responsible for any of these things, as soon as you become aware of them.

- Be proactive in attending to situations that could help or harm the organization, either by dealing with them yourself directly, or by finding and informing the people who can.

- Aim to give your best contribution, both through the work you are doing and in how you cooperate or directly collaborate with others.

- Take responsibility for your ongoing learning and development, and support others to do the same.

Key Concepts for Making Sense of Organizations

Whether you’re in a position of leadership and influence or simply looking to make a meaningful contribution in your organization, building and maintaining a common understanding with your colleagues about how the organization works is highly valuable for building and maintaining effectiveness and making the best use of everyone’s time.

This chapter offers a foundational introduction to several concepts that are applicable, no matter what kind of organization you are involved with. Together, they form a straightforward yet powerful conceptual model that will help you and your colleagues make better sense of what’s happening in your organization, communicate more clearly, and work together efficiently and effectively to respond to the numerous opportunities, demands, and challenges you face. Learning about these concepts is a worthwhile investment of time, no matter what context you are working in. Understanding these concepts is also a necessary prerequisite for understanding and getting the best out of many of the patterns in S3.

The key concepts in S3 are:

- Organization

- Purpose

- Intervention

- Organizational Driver

- Requirement

- Domain

- Governance

- Operations

- Policy

- Complexity

- Objection

This introduction provides an overview of these concepts: You’ll learn what each concept is about, how they interrelate, and why they are useful. In the sections that follow, we’ll go deeper into each one to help you understand more about their relevance and how you can use them to improve organizational effectiveness and perhaps even your life! Developing a thorough understanding of these concepts will help you get the best out of Sociocracy 3.0 and this Practical Guide.

At its core, an Organization is a group of people collaborating toward a common Purpose. In the pursuit of fulfilling the purpose, people make Interventions that ultimately lead to the delivery of products and services intended to meet the needs or desires of the customers they serve.

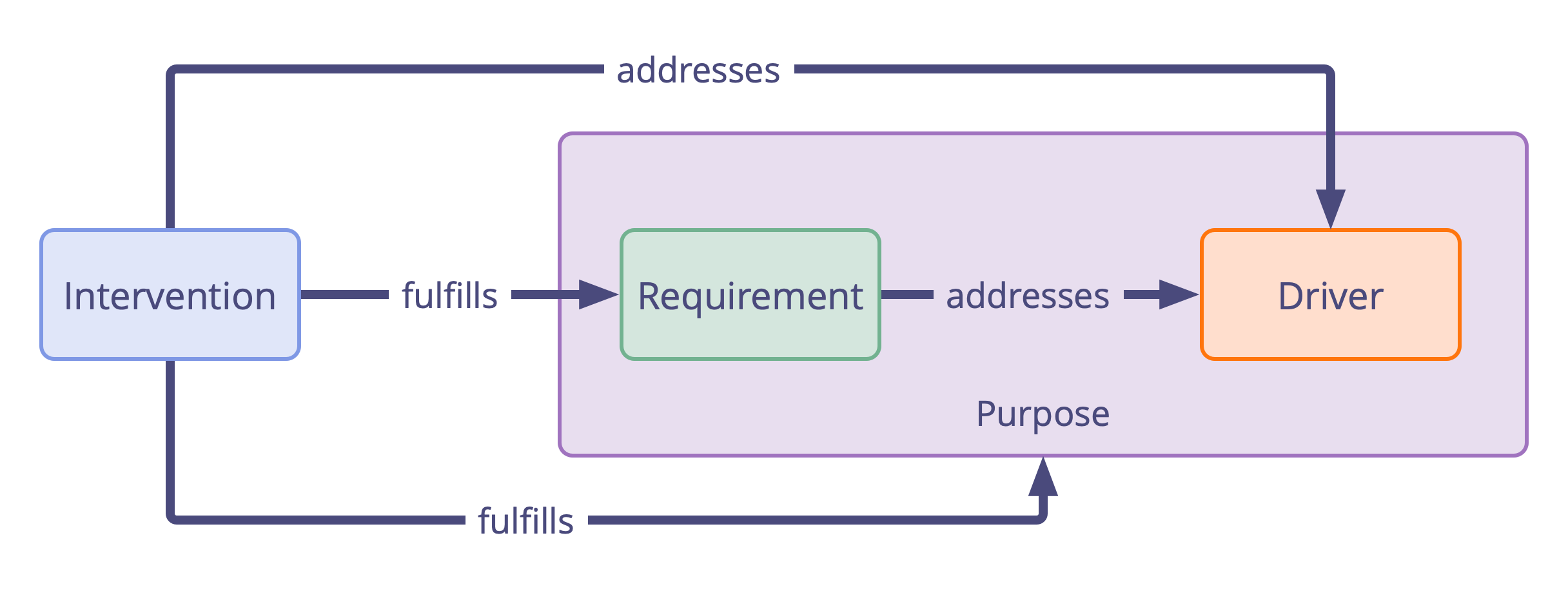

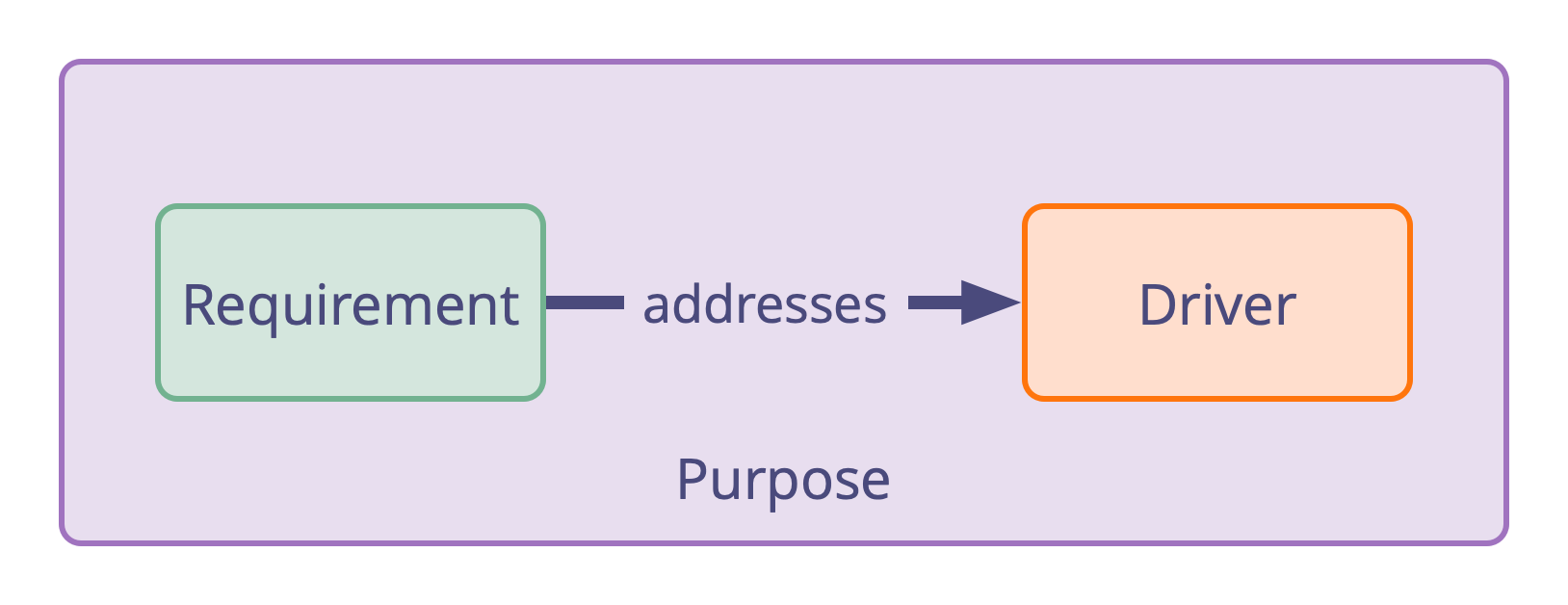

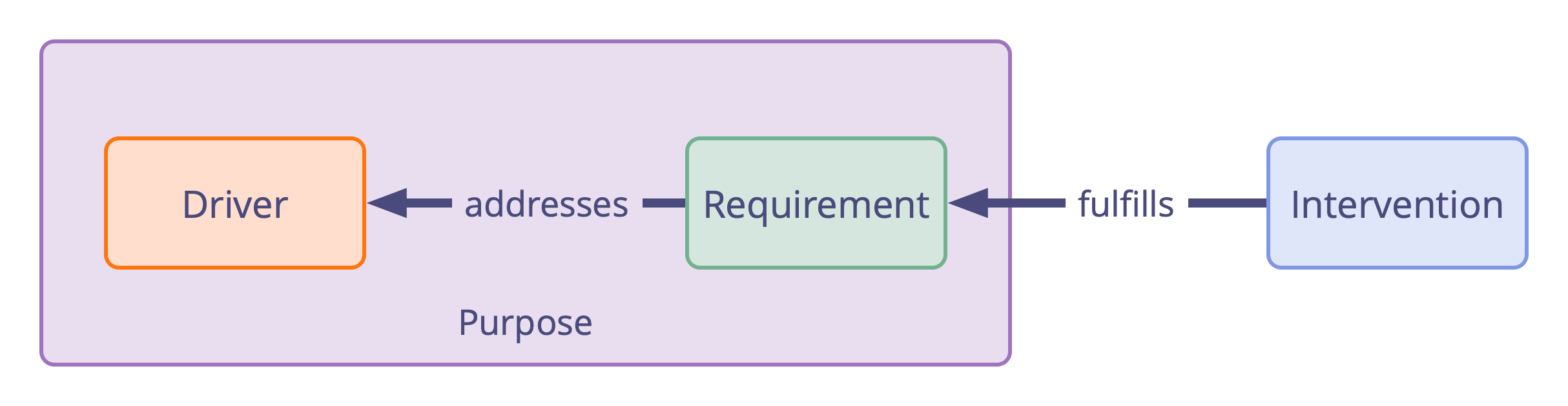

To describe purpose, we use two concepts: Organizational Driver and Requirement.

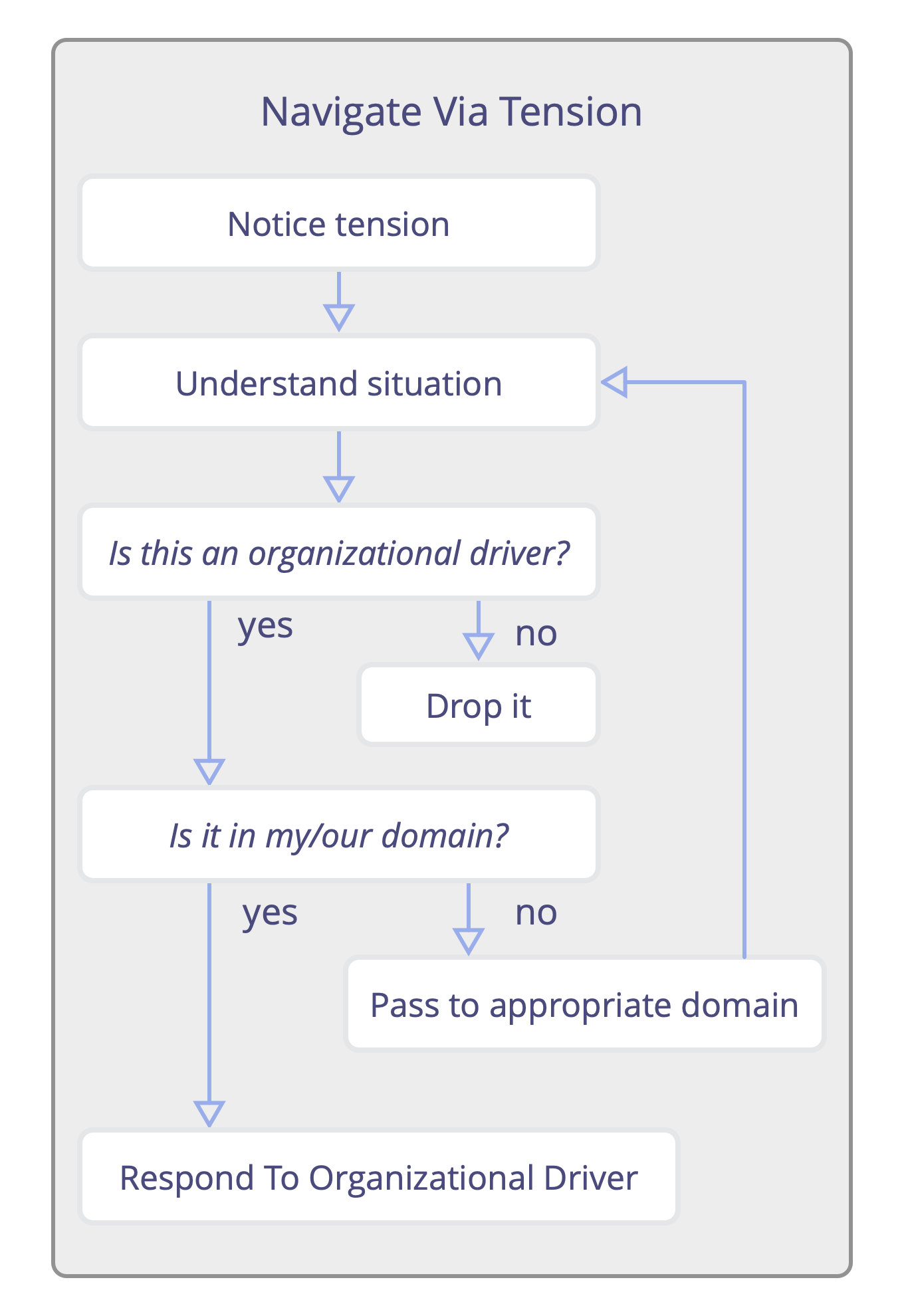

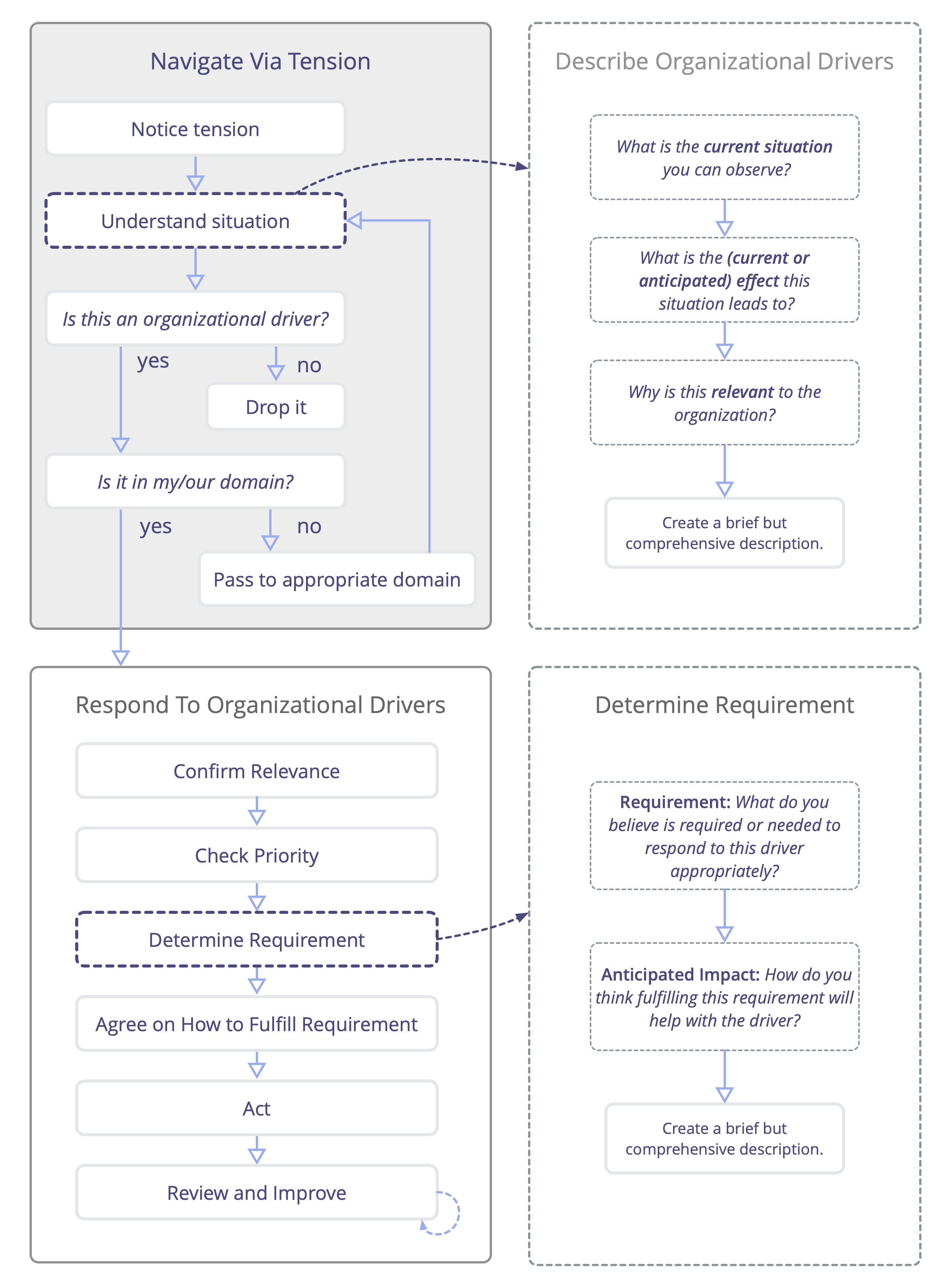

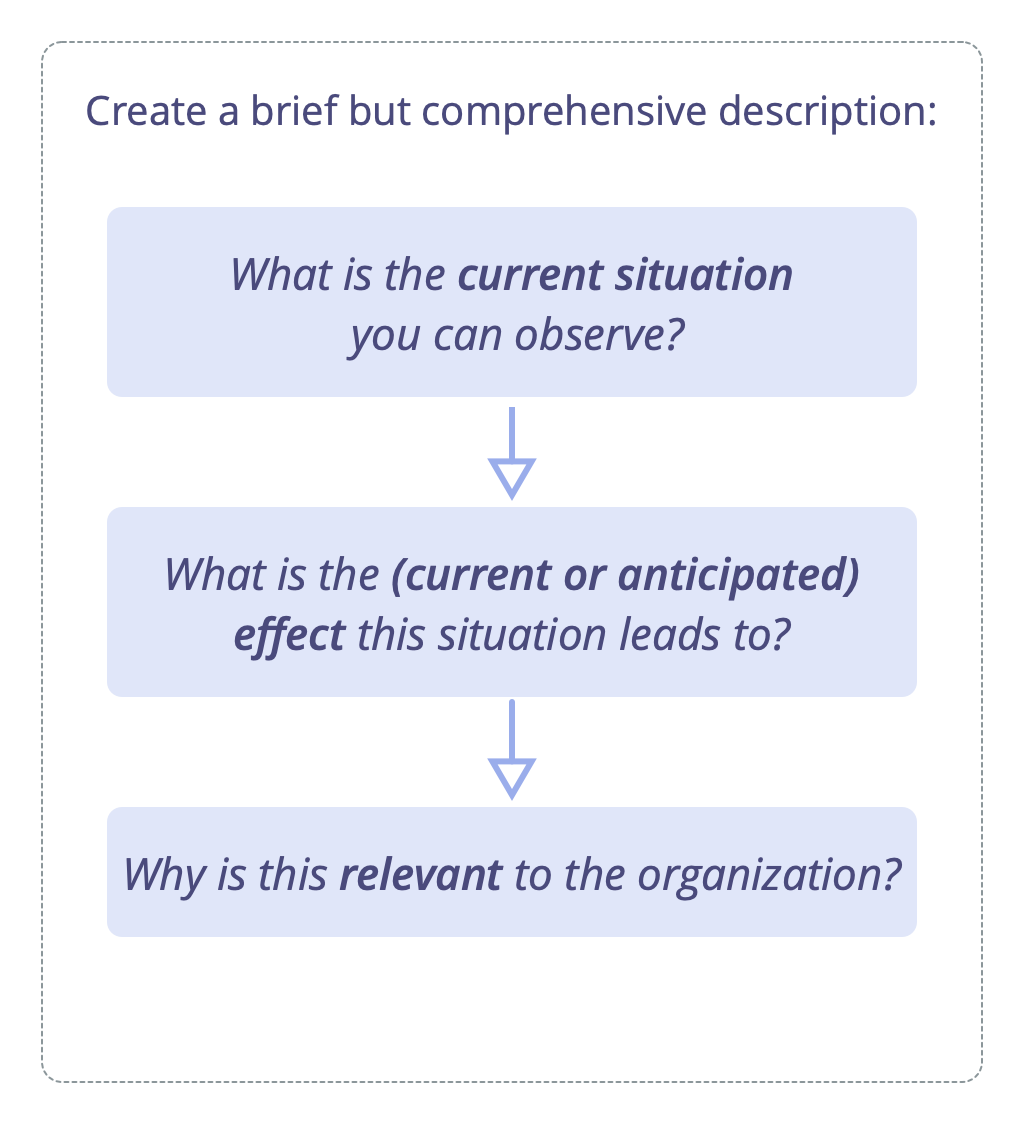

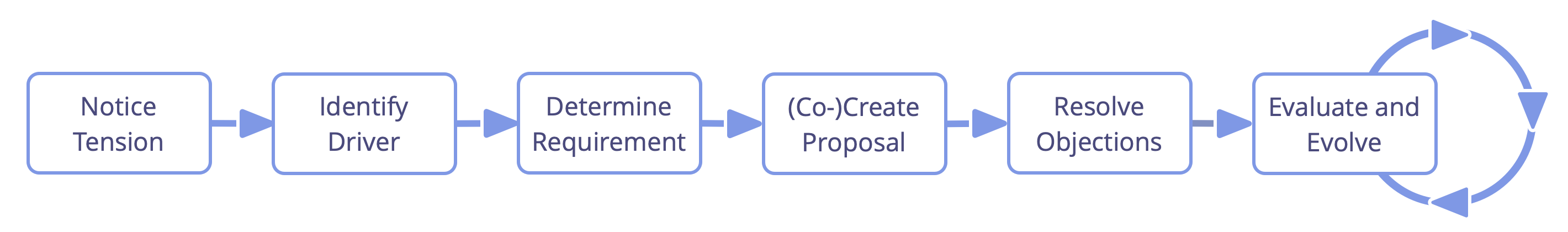

In their daily work, people face numerous situations that may be necessary or beneficial to respond to. It’s good practice to verify which situations are relevant for fulfilling the organization’s purpose, establish who has the responsibility and/or expertise to deal with them, and prioritize responding to them relative to other situations that are important. In Sociocracy 3.0 (S3), we refer to these situations as Organizational Drivers. By acknowledging organizational drivers and learning to articulate them clearly, you can improve shared understanding and communication regarding the numerous challenges and opportunities you face, which in turn can support effective prioritization and decision-making.

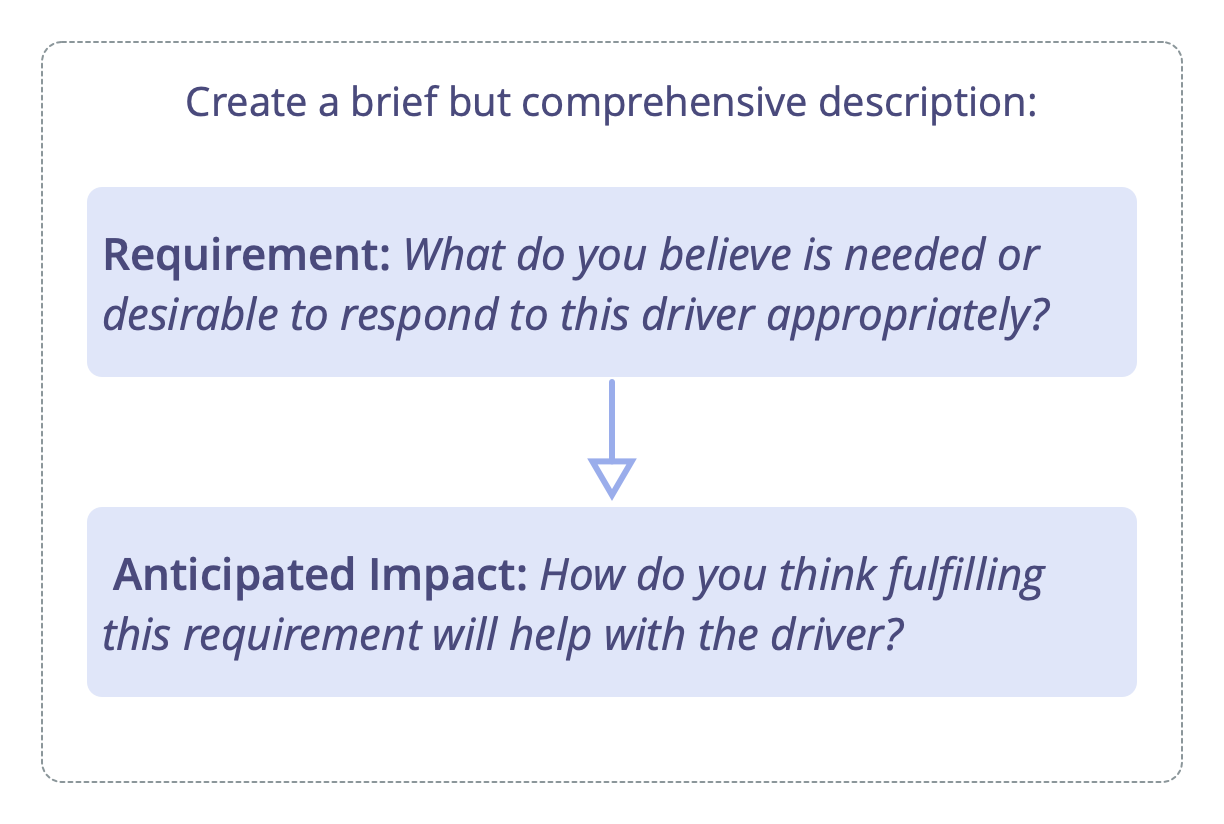

Once a priority driver has been identified, we suggest taking an additional step before making an intervention that addresses the situation — determining the Requirement: something you consider necessary or desirable to respond to the driver, either adequately or as a suitable incremental next step.

For some drivers, the corresponding requirement might be obvious, either because the situation is straightforward to deal with or because you have an existing policy in place that provides guidance on that. On all other occasions, determining the requirement will help clarify the general direction and scope for a suitable intervention while still leaving options open for creative thinking and exploration of various ideas for a specific intervention.

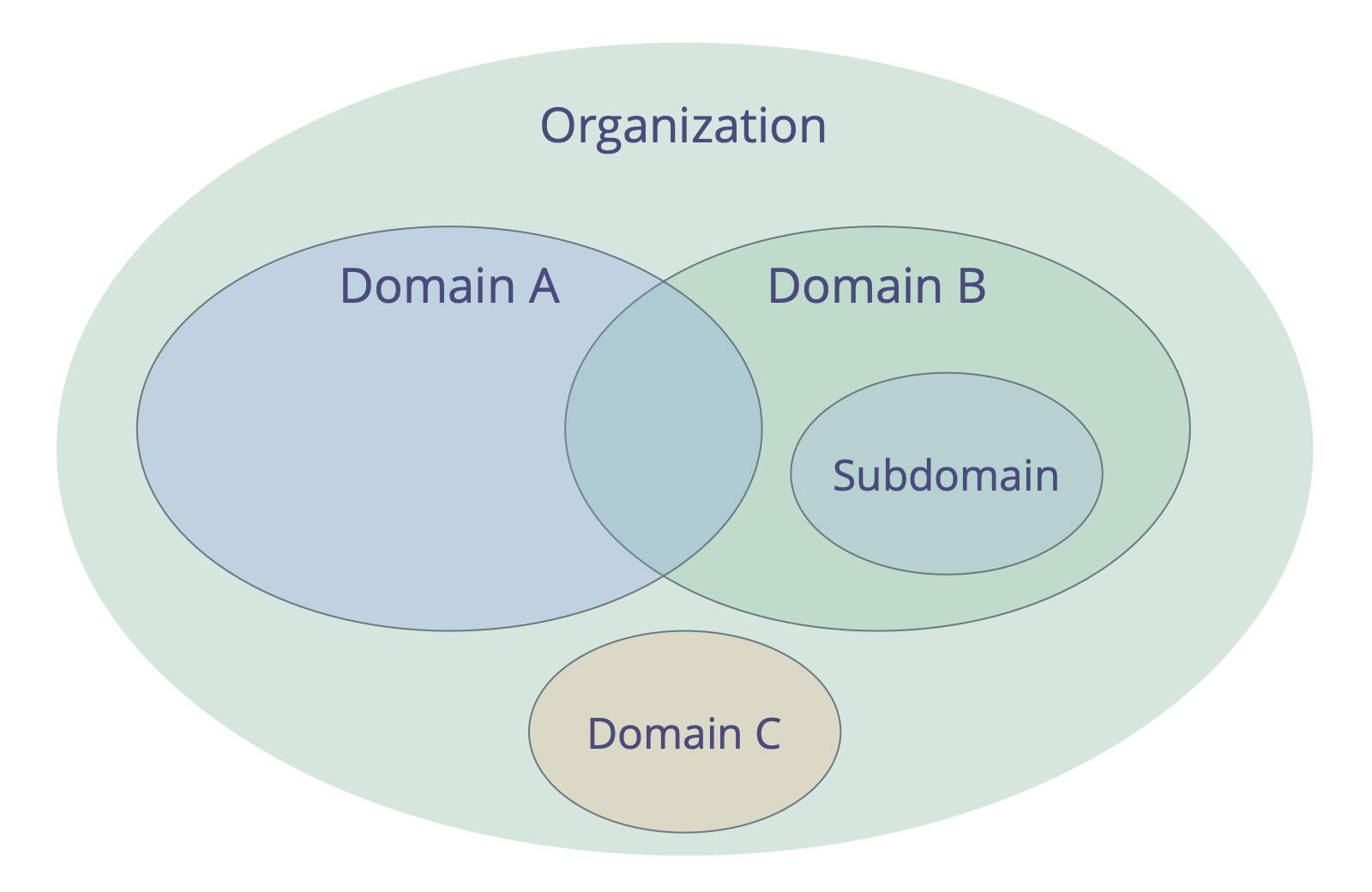

As people start working on fulfilling the overall purpose of the organization, they break down the work into smaller pieces, each of which has its own sub-purpose. Responsibility for fulfilling certain sub-purposes can be distributed among people as distinct areas of responsibility and authority. We refer to these areas as Domains. By dividing work into domains and clearly distributing responsibilities, organizations can clarify expectations, make the best use of people’s skills and experience, and ensure that important work gets addressed. This cohesive approach supports alignment with the organization’s purpose, contributing to its overall effectiveness and resilience while avoiding unnecessary dependencies and maintaining coherence throughout the system as a whole.

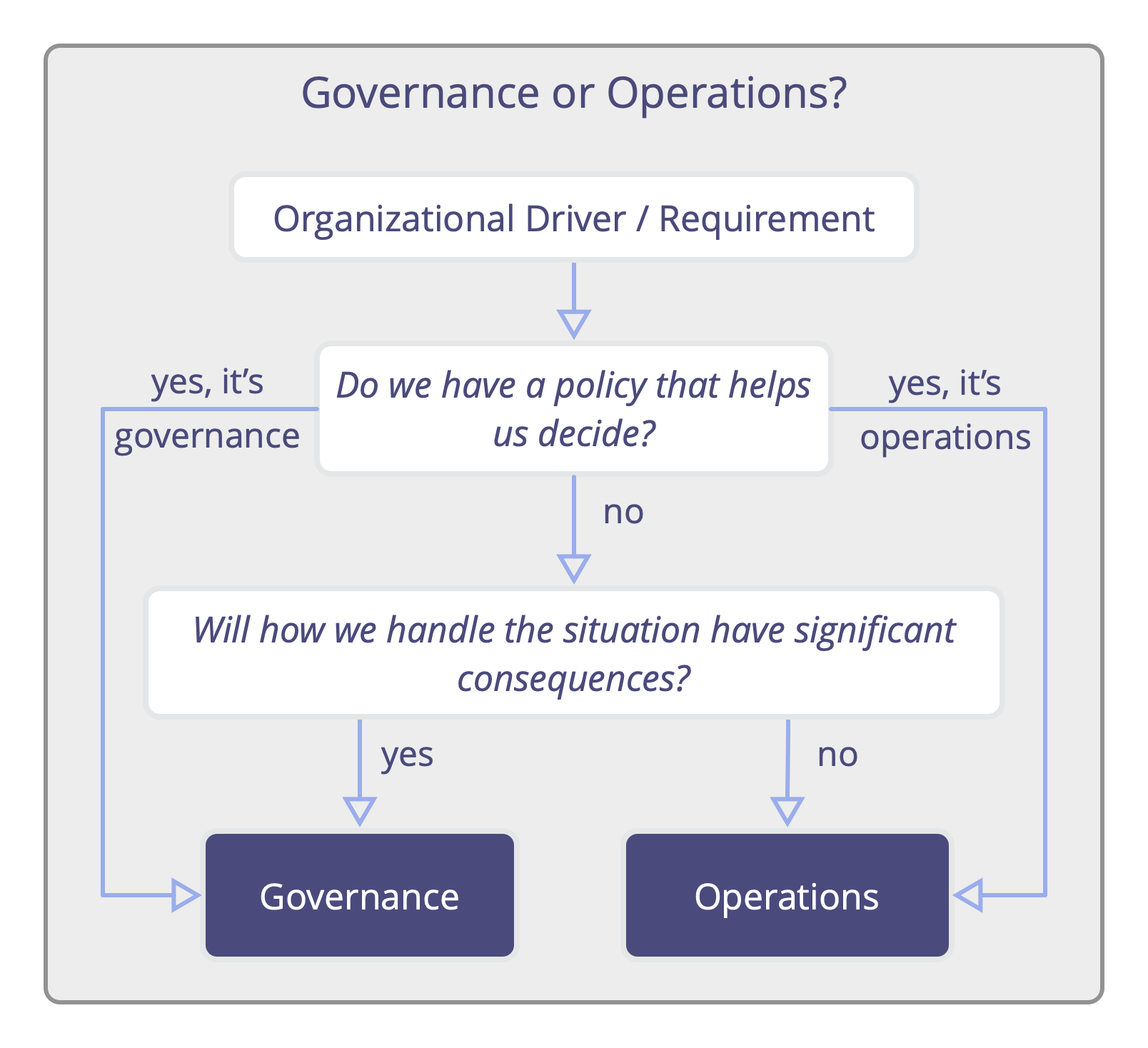

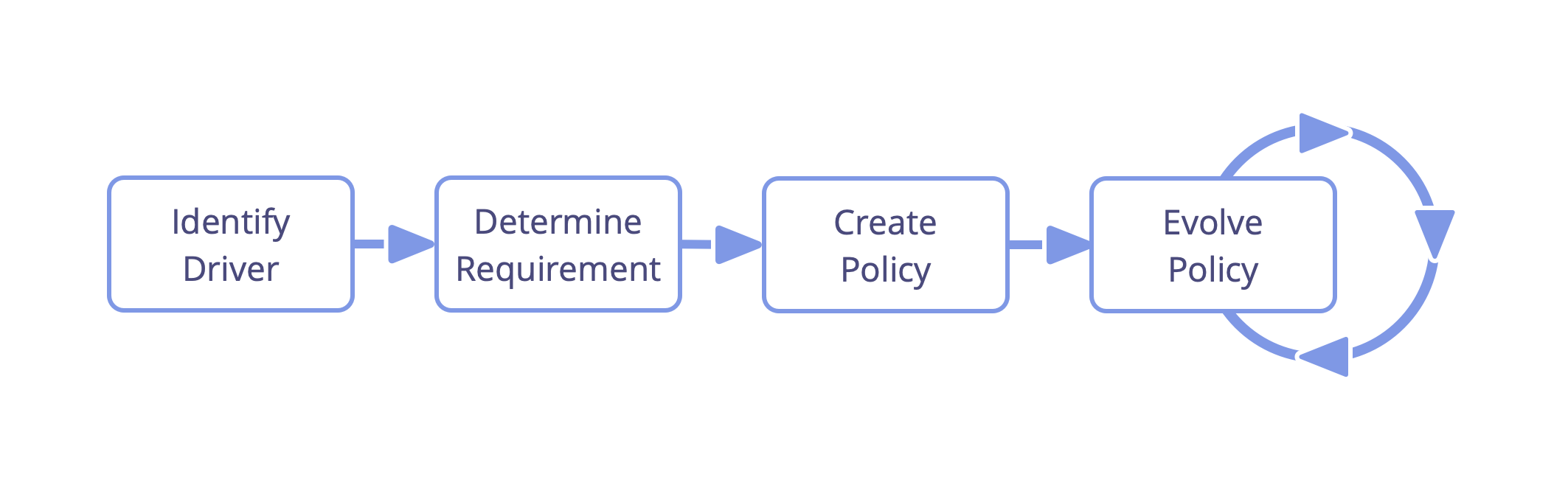

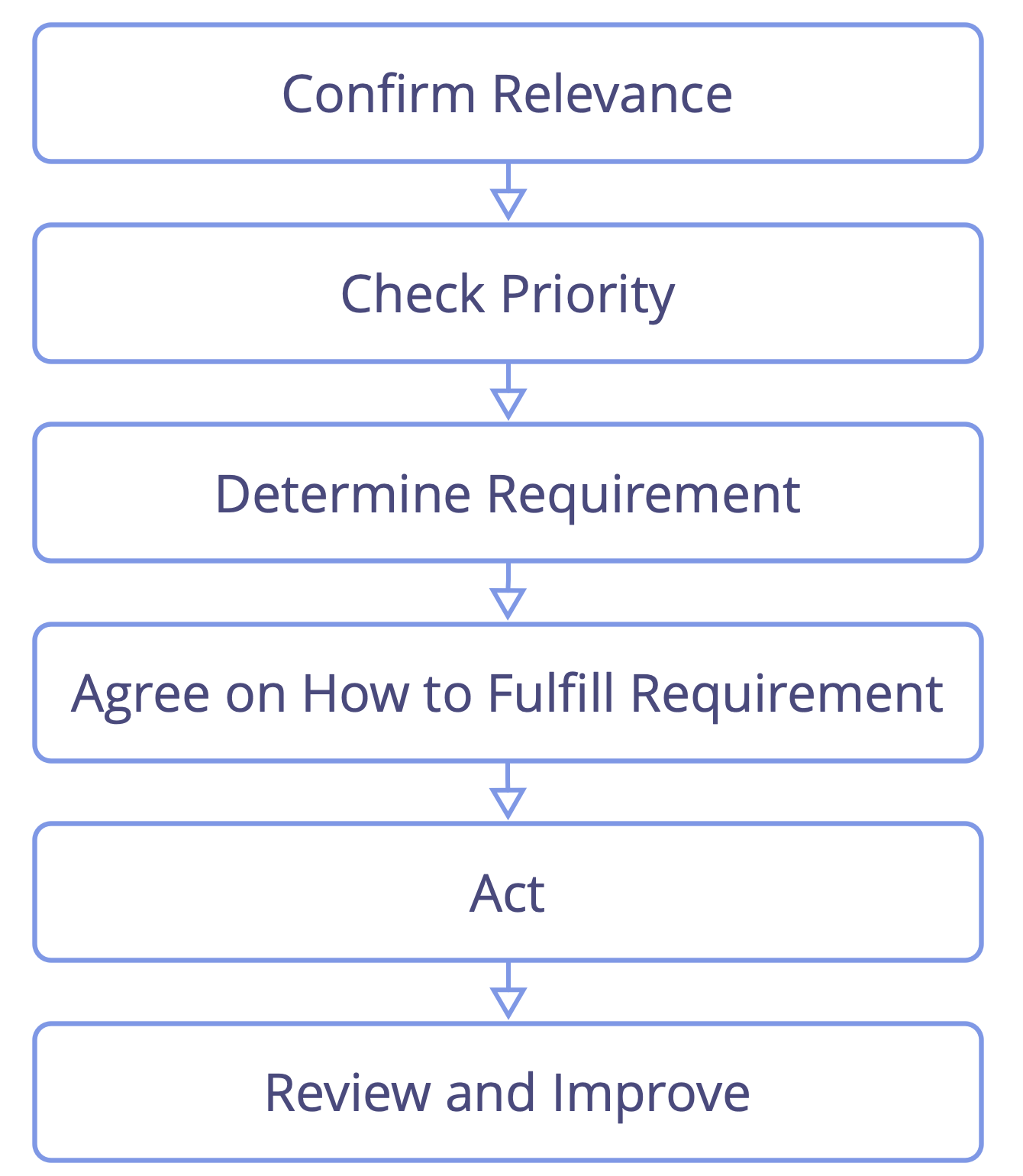

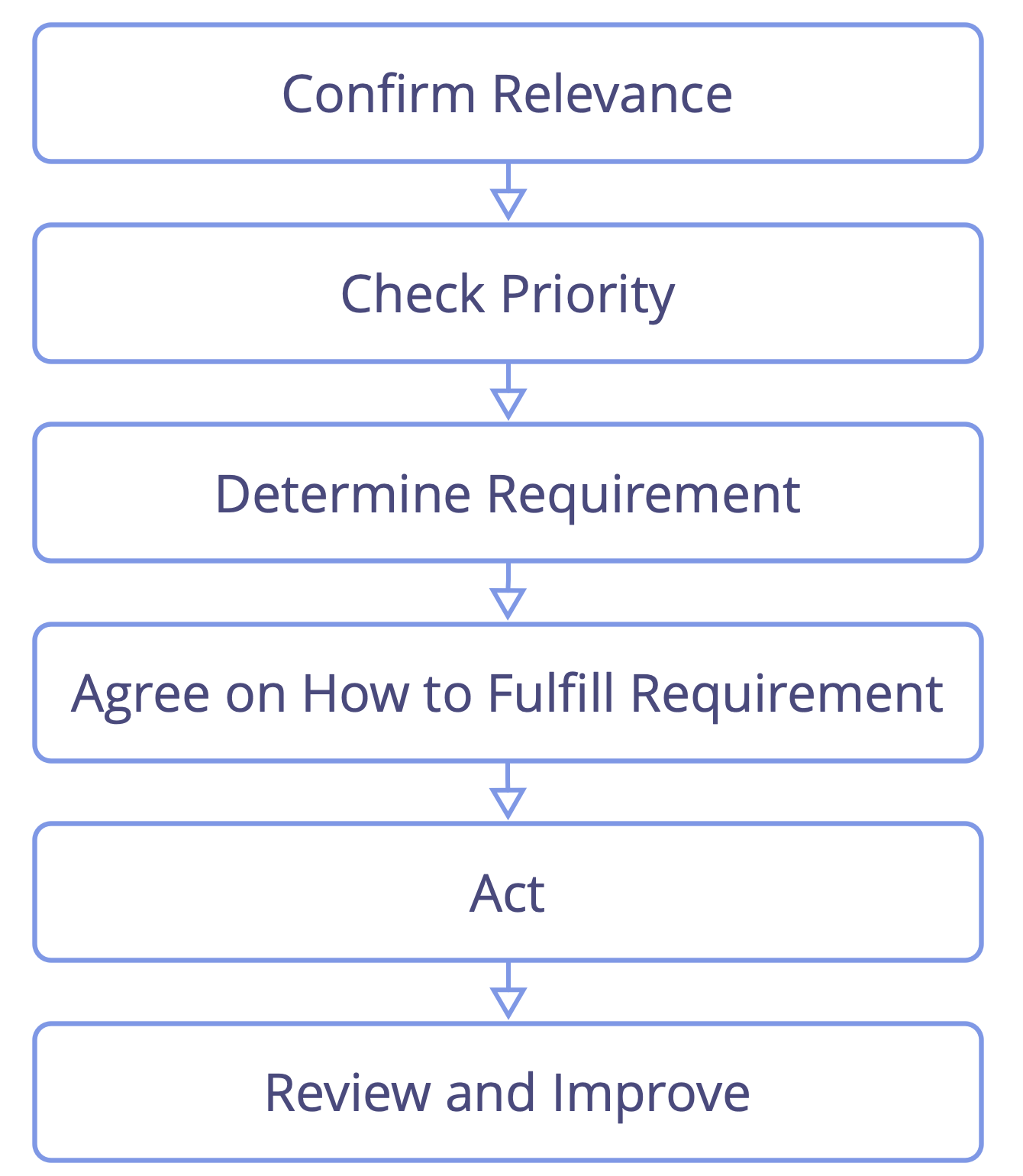

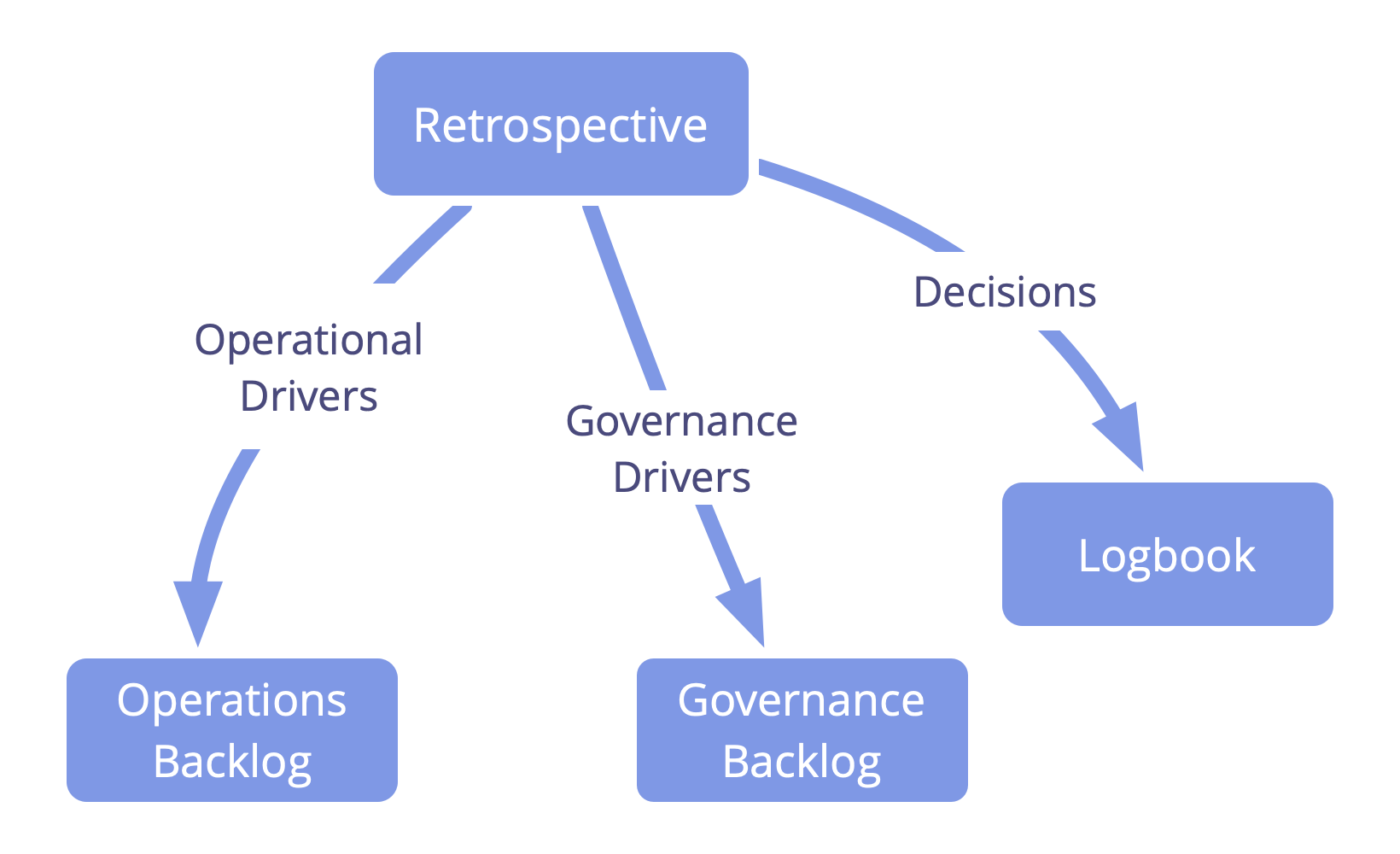

To deal with many of the requirements they are responsible for, people simply need to complete one or more tasks. We refer to these daily activities as Operations. Fulfilling more significant requirements, however, necessitates developing Policies (strategies, plans, guidelines, etc.) Policies are a specific type of intervention that govern how people should go about fulfilling a requirement. We refer to the activity of setting significant objectives — for the entire organization or specific people within it — and of making and evolving significant decisions that guide people toward achieving those objectives as Governance. Deciding on and evolving policies are the main activities of governance.

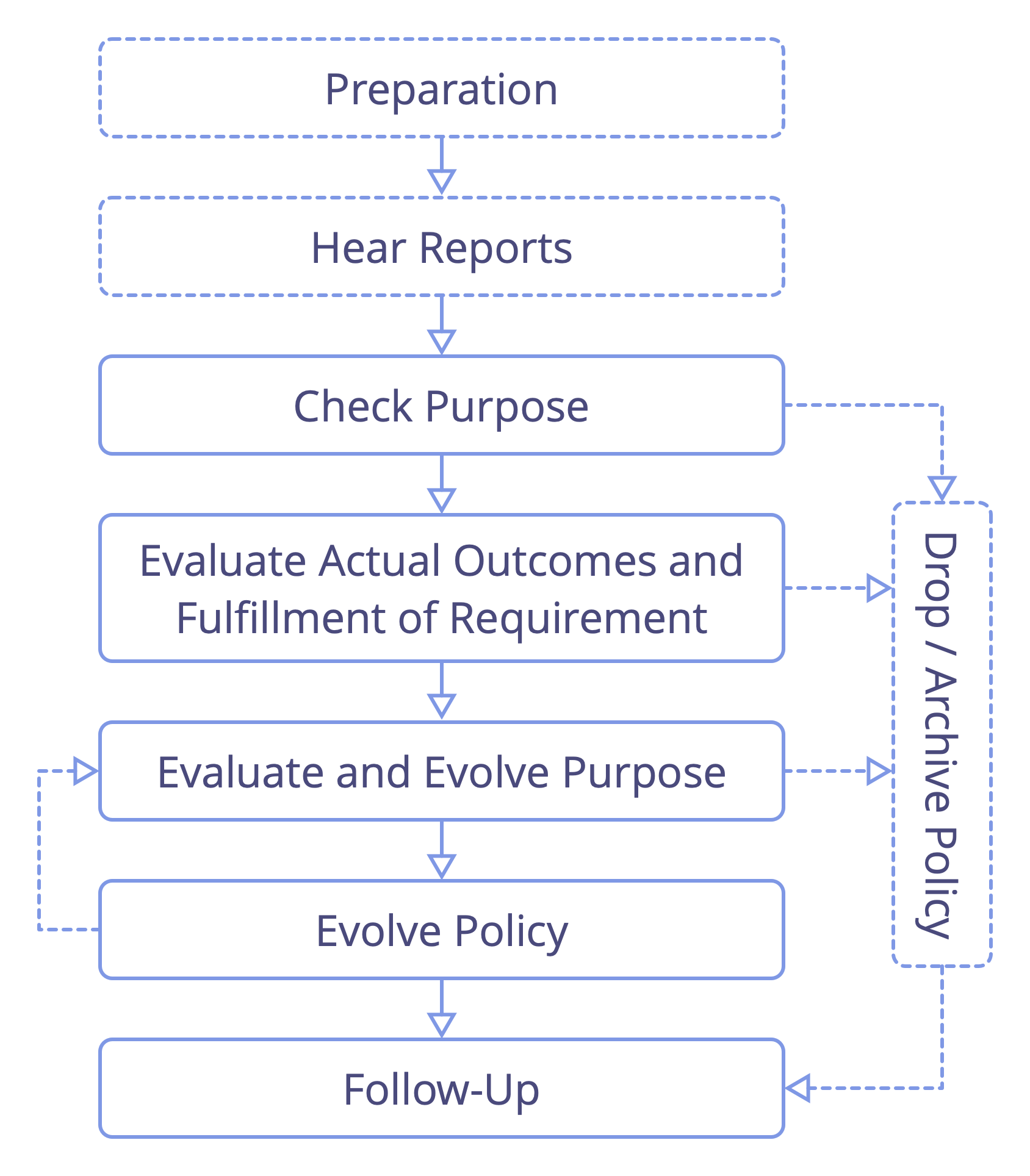

Since adhering to policies can significantly help or hinder the delivery of value, they are worth treating differently from less consequential decisions about day-to-day activity: Creating policies benefits from a deliberate and participatory approach, and the outcomes that result from implementing them should be evaluated regularly to identify what is working and what can be improved to ensure that they fulfill their intended purpose and remain relevant over time.

Making decisions on policy can feel daunting and overwhelming because there are so many things to consider, numerous risks and uncertainties, and solutions that appear obvious at first often turn out to make situations worse rather than improving them. That is because governance often deals with Complexity. Complexity is a property of a system in which a large number of elements are connected through an even larger number of relationships, interacting with each other and their environment in multiple ways.

In complexity, it is hard to predict the outcomes of interventions you make. Similarly, you can’t expect a policy to be correct or suitable, or even if it is initially, that it will remain so over time. Therefore, it is important to treat all policies and decisions as provisional and to regularly evaluate and adapt them when opportunities for improvement are discovered.

To better manage the complexity of governance, it’s beneficial to take a collaborative approach to decision-making that integrates different people’s perspectives, experiences, and expertise when developing policies. To maintain the effectiveness of collaborative decision-making, it’s important to consider who needs to be involved in which decision, in what way, and to what degree. A simple tool for harnessing distributed cognition is inviting people with a relevant perspective to share Objections: arguments that reveal undesirable consequences or risks or demonstrate worthwhile ways to improve a policy, a proposal, or an activity. As we explain in the section on the Principle of Consent, by raising, seeking out, and resolving objections, you focus people’s contribution toward ensuring that decisions and activities are improved whenever possible and align, so far as people can tell, with achieving the organization’s short-term and long-term goals.

Throughout this guide, you’ll learn about a wide array of Patterns — templates of processes, practices, and guidelines for successfully responding to specific challenges or opportunities people in organizations face. These patterns build on the other key concepts and are aligned with the Seven Principles. These patterns can be applied individually, adapted, and combined to address your specific organizational needs. By choosing patterns according to your current requirements, you can take an iterative and incremental approach to organizational change.

The concepts introduced above are not just informative — they have many practical applications for anyone seeking to lead or participate in an organization that not only survives but thrives.

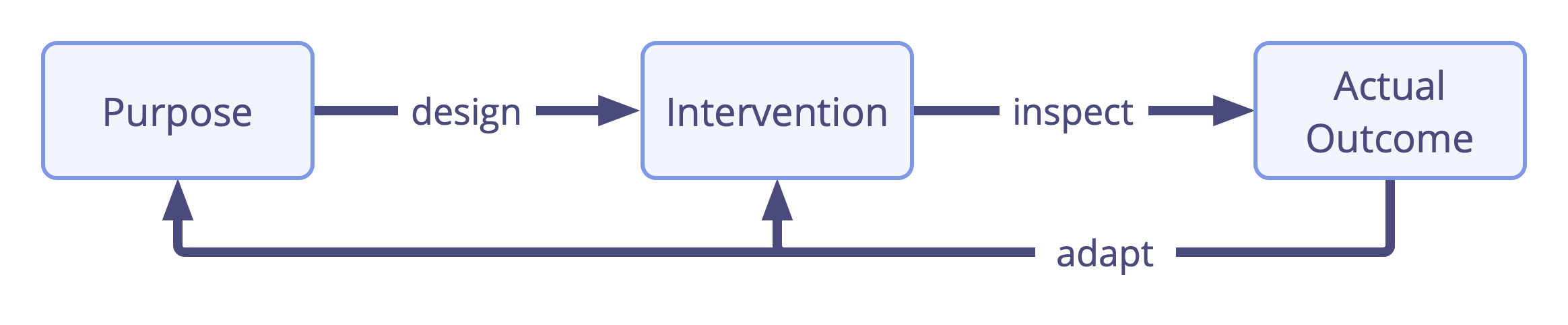

A Model for Purposeful Action

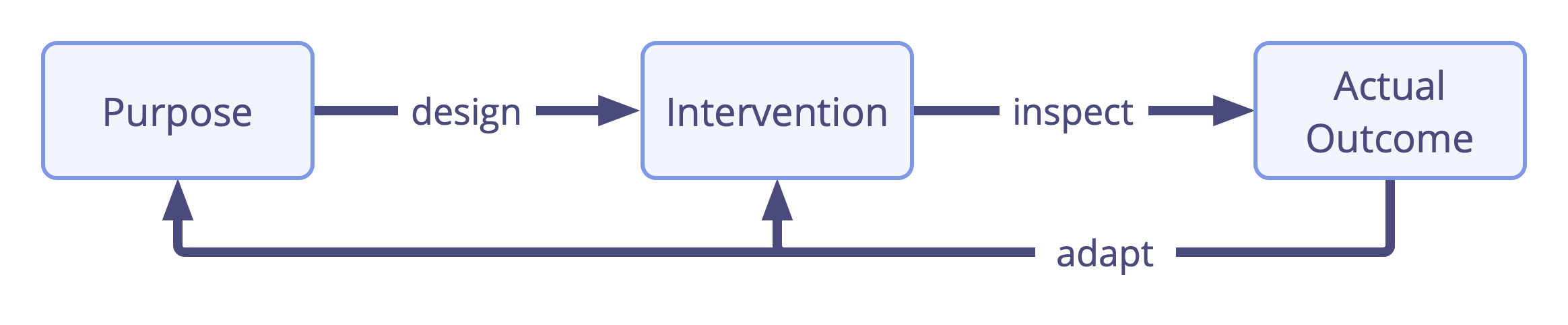

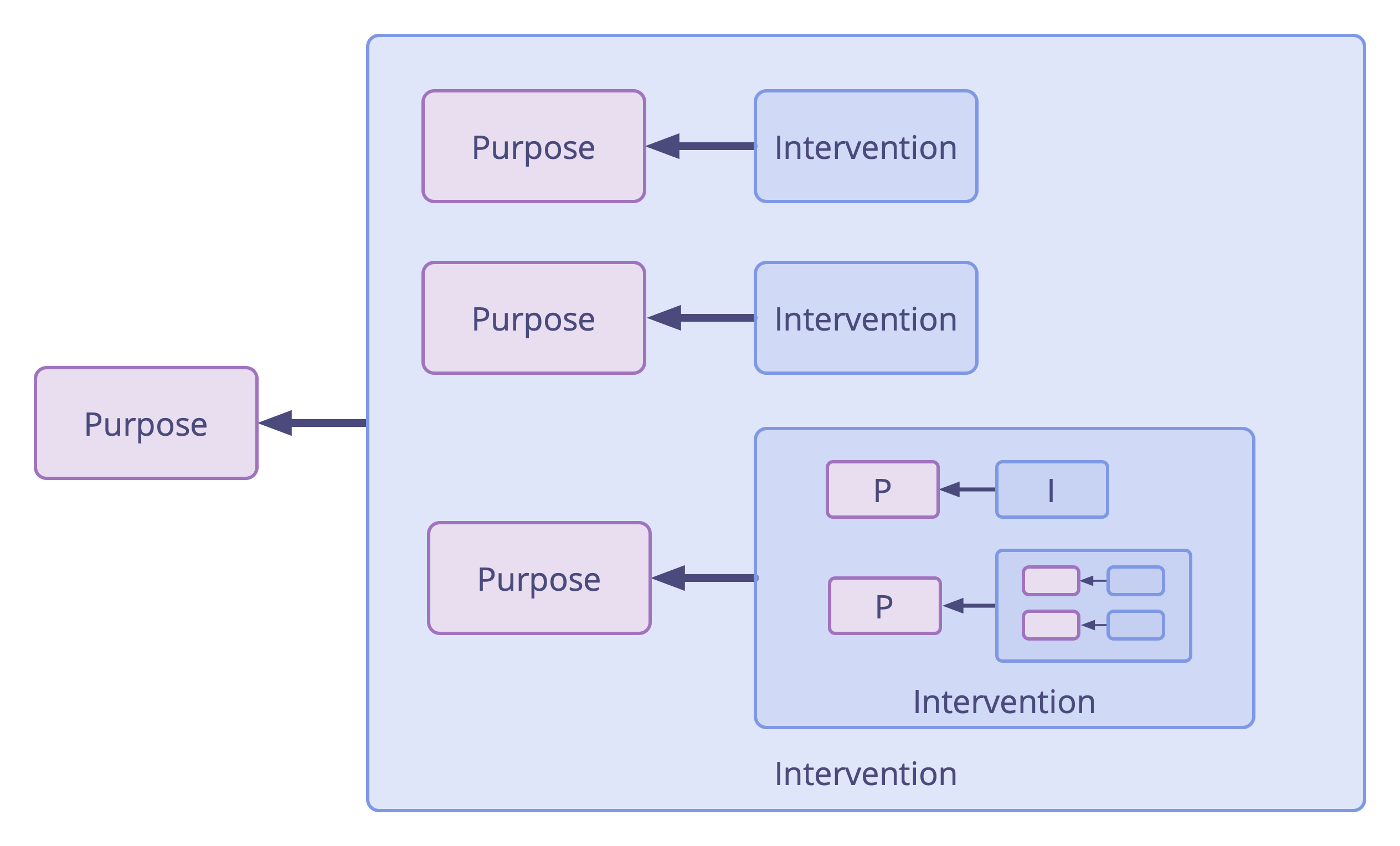

One way to understand work in organizations is as people making interventions to fulfill a purpose.

Purpose informs, motivates, and guides action. Interventions are specific steps people take, and/or the constraints they put in place, to fulfill a purpose.

Although people making interventions to fulfill a purpose sounds intuitive and straightforward, in practice, there are many fail points that can lead to undesirable consequences or waste. Common examples include the following:

- Lack of clarity around objectives: People act without understanding the purpose behind what they are doing.

- Misalignment: The purpose of a specific decision or action does not align with the organization’s broader goals or priorities.

- Disagreement on viability: There is disagreement about whether a purpose is valuable or worth pursuing.

- Divergent opinions: People have differing views about the purpose behind a decision or activity.

- Diverse implementation perspectives: People have different perspectives on how to fulfill a purpose.

- Ineffective interventions: The activities intended to fulfill a purpose turn out to be unsuitable or insufficient, from the beginning, or because circumstances changed in the meantime.

- Lack of effective feedback loops: There is no review of whether interventions are achieving their purpose, or no follow-up to improve or adapt them.

It’s much easier to avoid or at least detect and mitigate those fail points when all stakeholders share a common understanding about how to describe and discuss purpose and interventions clearly and coherently.

Understanding and describing interventions is often straightforward; you list the specific step(s) you take and/or the constraint(s) you put in place to fulfill a purpose. Clearly understanding and describing purpose, however, can be more challenging, and there are several ways to do it.

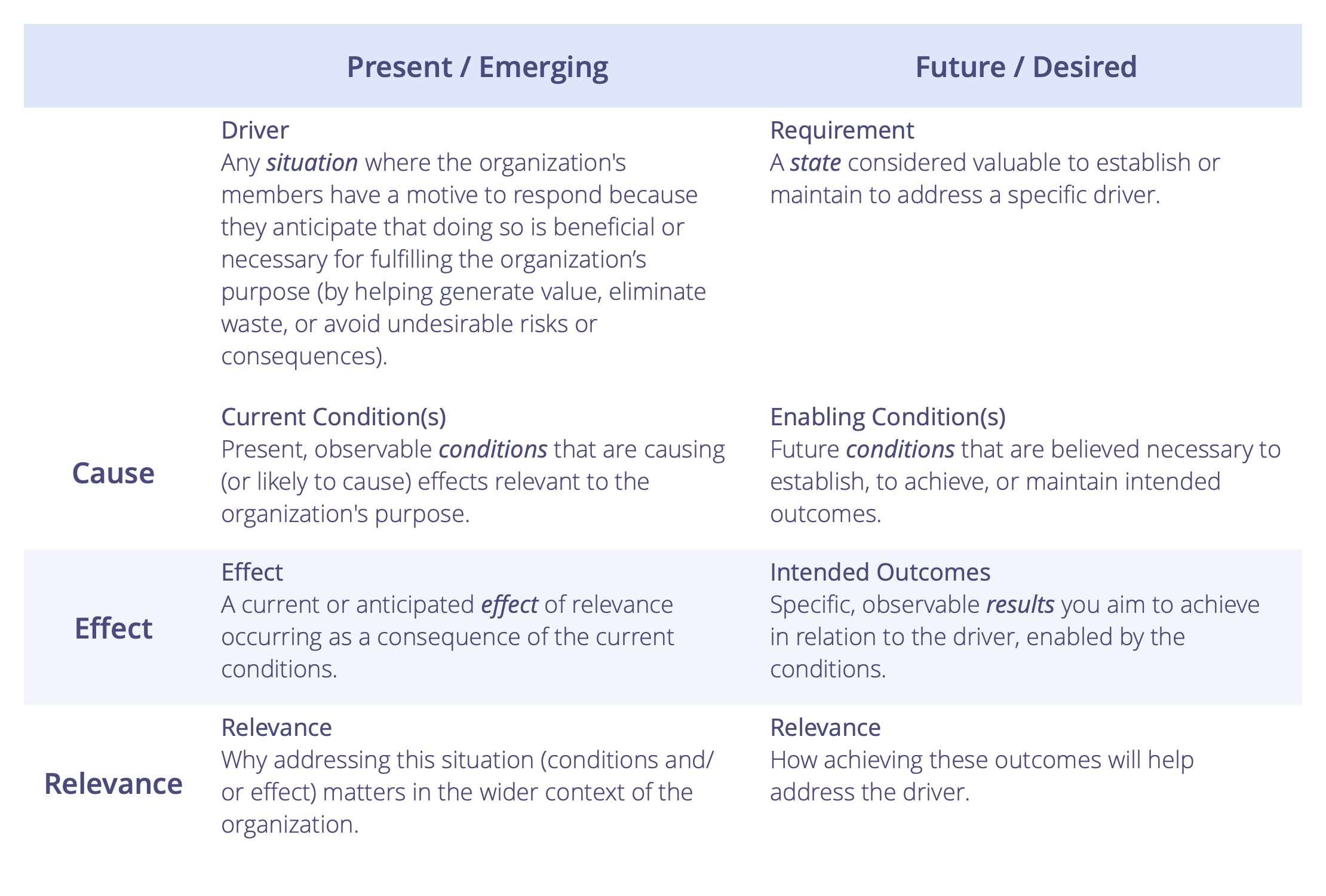

One way to understand purpose is as the confluence of a situation that is relevant to address, and the outcomes considered valuable to achieve in relation to that situation. To define purpose, we use two concepts:

- Organizational Driver: a situation of relevance that you want to address.

- Requirement: a state considered valuable to establish or maintain in order to address a specific driver.

Clarifying both the organizational driver and the associated requirement makes it much easier to determine a suitable intervention.

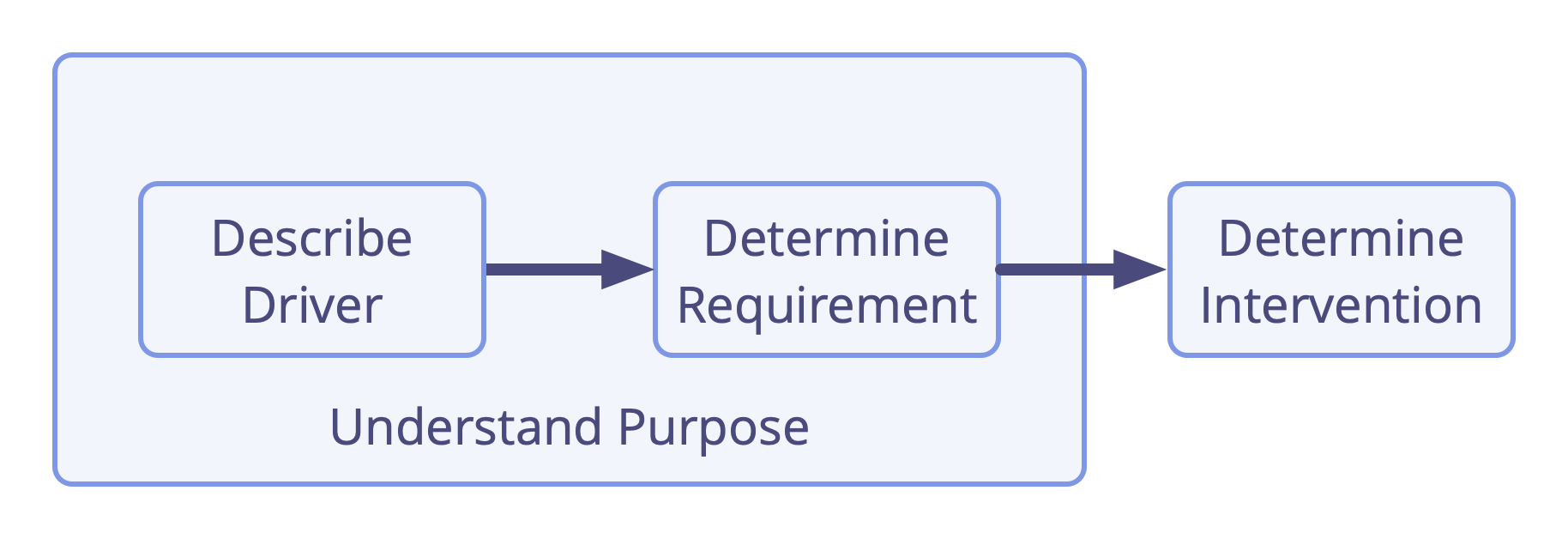

There is also a natural sequence to this approach: A clear understanding of the situation of relevance is essential to determine a suitable requirement. Understanding the requirement itself (or at least, a grasp of a valuable outcome) is necessary to determine an appropriate intervention.

Breaking down the process of responding to relevant situations into distinct, sequential steps helps prevent misdiagnosis, reduce wasted effort, and avoid implementing solutions that fail to address the situation in a suitable way.

This model also helps to visualize interconnected purposes, supports shared understanding, better communication, and more effective evaluation of whether specific interventions are achieving the outcomes intended.

Ensuring coherence is often complex: each intervention needs to be suitable for fulfilling the purpose it is intended to serve, but it must not impede the fulfillment of other organizational purposes. It also needs to be aligned with and valuable in light of the organization’s overarching goals. This complexity arises from the interconnected and interdependent nature of things and from the difficulty of clearly delineating where one aspect ends and another begins.

In essence, for people in organizations, this framework serves as a practical roadmap that turns vague intentions into concrete, purposeful actions. It supports better resource utilization, stronger alignment, a more focused approach toward achieving meaningful outcomes, and greater capacity for learning and adaptation over time, as supported by the patterns in S3.

How the Model Helps

The model for purposeful action provides a lightweight and conceptual framework that reveals a simple underlying architecture behind all decision-making and activity in organizations.

The model can shift how people perceive organizational dynamics through the conversations it triggers. By understanding purpose, relevance, and relationship to the whole, people begin to “see the system” — recognizing interconnections between decisions and their relation to overarching purpose. This reframing is often transformational.

On the most fundamental level, the model helps people understand why they should act and to what end before they decide what to do and how. It enables insight into relationships between decisions by connecting and aligning what you decide and do with what other people are doing in the organization. It helps surface misalignments (e.g., interventions happening in parallel that should be connected but aren’t), supporting learning and adaptation across systems.

It can be used to map out, understand, and evolve the structure of interrelated purposes and interventions throughout the entire organization, from the purpose of the organization itself, all the way down to any simple operational intervention.

While applicable across many contexts, the model is specifically designed to support organizational life: it brings attention to purposeful activity, facilitates coherence across interdependent efforts, and encourages learning and adaptation over time.

The model is universally applicable, regardless of your organization’s structure and how you choose to categorize and manage work and decision-making.

Once you understand the concepts and relationships this model is built on, you can start using it right away — both for your own thought process and in your conversations with others — to improve your capacity for sense-making, meaning-making, and decision-making, and increase your chances of recognizing what’s working and what may be valuable to change or improve.

The model also works seamlessly with any tools you are currently using for visualizing decisions and work, from pen and paper and wall boards to Miro, Jira, or Google Suite.

Purpose

Everything you do serves a purpose, even if you might not always consciously choose that purpose or be aware of it. Deliberately considering the purpose before taking action helps ensure that your actions contribute to achieving that purpose. What seems purposeful in isolation might not make sense when you step back and look at the bigger picture. To make the best use of resources, energy, and time, the purpose of your actions must align with your broader goals. This applies to organizations as well.

Purpose is the reason why something is done, used, or created; a guiding motivation that directs actions, decisions, and resources toward achieving a valuable outcome.

Considering purpose helps people make sense of what’s important to focus on and fosters a shared understanding of what may or may not be beneficial to do.

Reflecting on purpose supports:

- Sense-making: understanding situations that motivate action

- Meaning-making: establishing whether and why a situation is relevant to respond to

- Decision-Making: determining direction and scope for a suitable response to the situation

Purpose at the Center of the Organization

Every organization has an overall purpose it serves, whether it’s explicitly defined and widely understood or not, and the effectiveness of an organization depends on its members’ ability to contribute toward fulfilling that purpose.

Therefore, ensuring the overall purpose is clear and explicit helps members align their priorities and actions to that purpose while avoiding wasting effort on activities that do not contribute meaningfully.

As an organization evolves and the context in which it operates changes over time, its overall purpose might need to be refined to ensure the organization remains relevant and effective. This is why it’s essential to periodically evaluate whether the organization’s purpose is still worthwhile pursuing and to determine whether adjustments are valuable or required.

Just as a project or team within an organization can outlive its relevance, the organization itself may reach a point where its purpose is no longer meaningful in its broader context. At that point, the organization must either redefine its purpose or cease to exist.

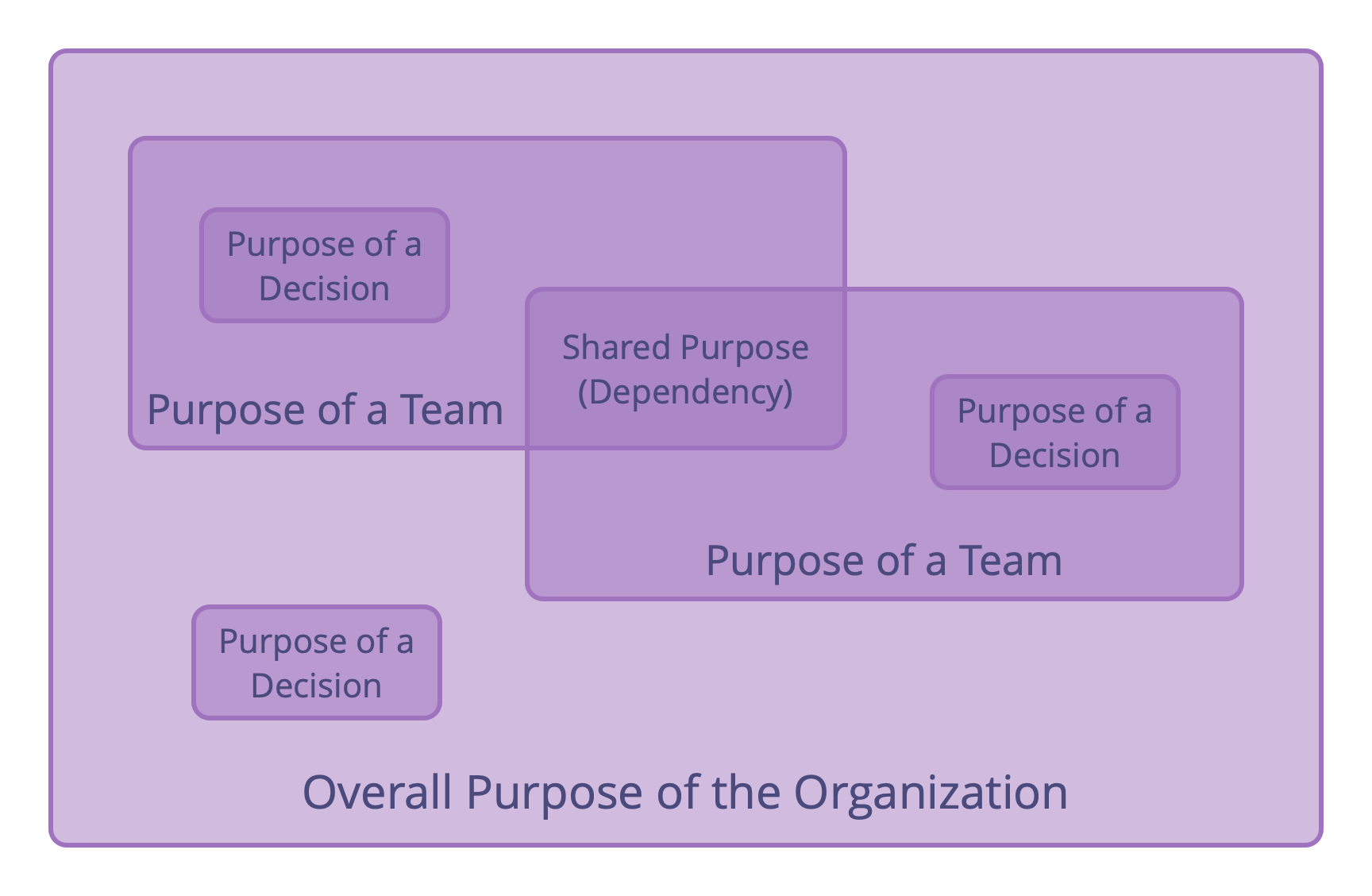

Organizations are Complex Networks of Interrelated Purposes

Within an organization, each team, role, decision, and action serves a purpose — whether that purpose is known, clearly understood, and defined or not. For an organization to be effective, it’s important that every purpose people work toward fulfilling contributes to the organization’s overall purpose and is not in contradiction to another purpose elsewhere in the organization. Similarly, and in addition to that, for a team or project to be effective, decisions and actions within a team or a project must also align with that team’s or project’s purpose and must not contradict any other decision or action.

Without such coherence, an organization may face numerous undesirable outcomes, such as conflicting decisions, unclear responsibilities, duplication of effort, or failure to take care of important work.

As an organization grows, complexity increases, and the connection between our interventions — the actions we take and the rules we put in place — and the organization’s overall purpose becomes difficult to track and understand.

Developing and maintaining coherence across this complex, dynamic network of interrelated purposes is both necessary and challenging. It requires ongoing monitoring and evaluation of purposes, interventions, and actual outcomes to ensure that what works is reinforced and what does not is adapted or discarded.

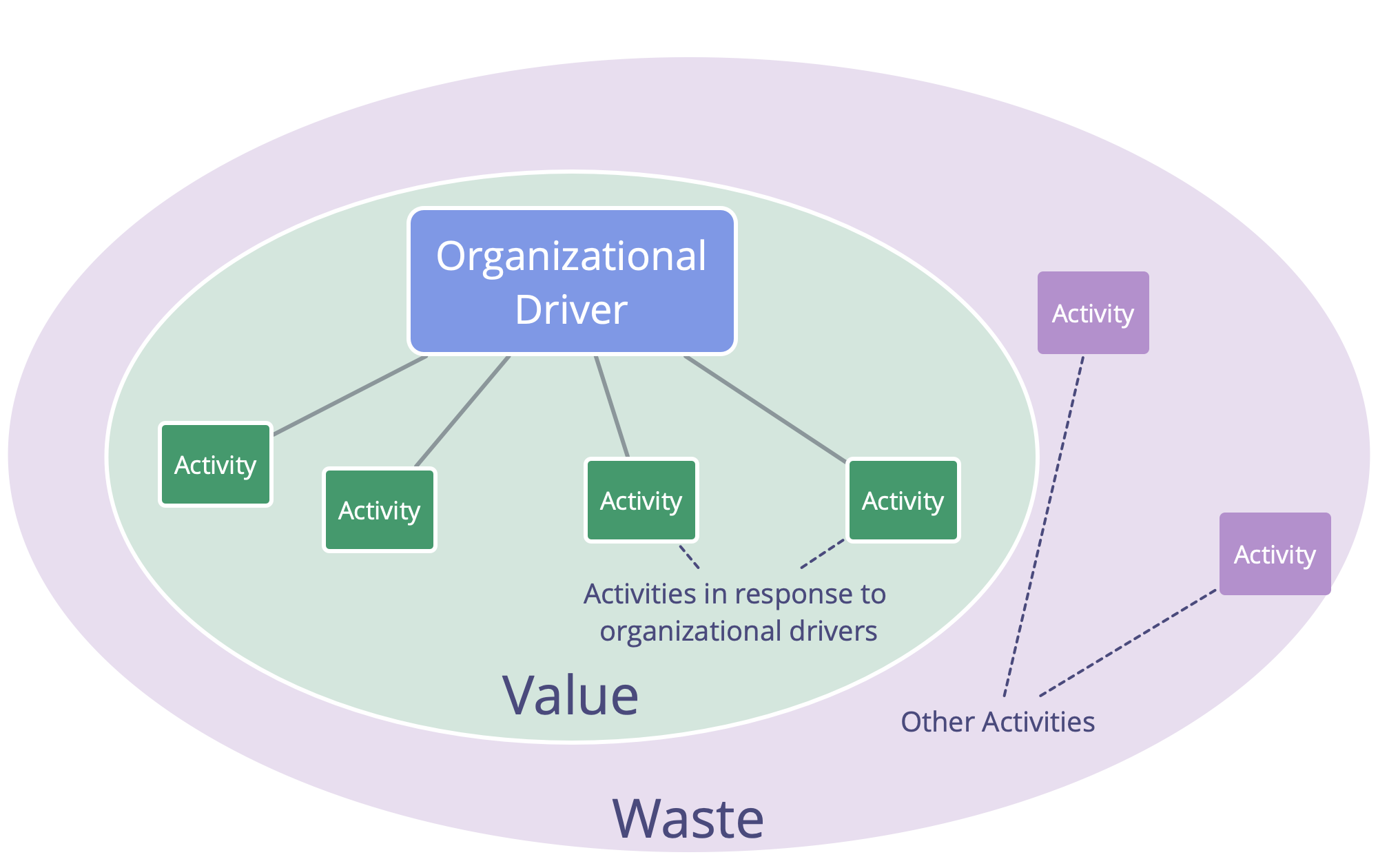

Purpose, Value, and Waste

Understanding this interrelated network of purposes provides a useful lens for evaluating value and waste in organizations. This perspective also makes many practices and ideas from lean production and lean software development immediately applicable for organizations pulling in S3 patterns, such as the Kanban Method or Value Stream Mapping.

In S3, both concepts are explained in relation to purpose:

Value is the importance, worth or usefulness of something for fulfilling a purpose.

Waste, in relation to purpose, is any activity, output, or use of resources that does not contribute — directly or indirectly — to fulfilling that purpose.